Ishirō Honda

Ishirō Honda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

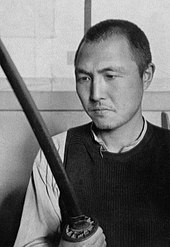

Honda at the National Museum of Nature and Science during the filming of Frankenstein vs. Baragon | |||||

| Born | 7 May 1911 | ||||

| Died | 28 February 1993 (aged 81) Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan | ||||

| Resting place | Fuji Cemetery, Oyama, Shizuoka, Japan 35°22′11″N 138°54′28″E / 35.3696°N 138.9079°E | ||||

| Alma mater | Nihon University | ||||

| Occupations |

| ||||

| Years active | 1934–1992 | ||||

| Known for |

| ||||

| Spouse |

Kimi Yamazaki (m. 1939) | ||||

| Children | 2 | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | |||||

| Years of service | 1934–1946 | ||||

| Rank | |||||

| Battles / wars | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 本多 猪四郎 | ||||

| Hiragana | ほんだ いしろう[2] | ||||

| |||||

| Website | ishirohonda.com | ||||

| Signature | |||||

| |||||

Ishirō Honda[a] (Japanese: 本多 猪四郎, Hepburn: Honda Ishirō, 7 May 1911 – 28 February 1993) was a Japanese filmmaker who directed 46 feature films in a career spanning five decades.[6] He is acknowledged as the most internationally successful Japanese filmmaker prior to Hayao Miyazaki and one of the founders of modern disaster film, with his films having a significant influence on the film industry.[7] Despite directing many drama, war, documentary, and comedy films, Honda is best remembered for directing and co-creating the kaiju genre with special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya.[8]

Honda entered the Japanese film industry in 1934, working as the third assistant director on Sotoji Kimura's The Elderly Commoner's Life Study.[9] After 15 years of working on numerous films as an assistant director, he made his directorial debut with the short documentary film Ise-Shima (1949). Honda's first feature film, The Blue Pearl (1952), was a critical success in Japan at the time and would lead him to direct three subsequent drama films.

In 1954, Honda directed and co-wrote Godzilla, which became a box office success in Japan and was nominated for two Japanese Movie Association awards. Because of the film's commercial success in Japan, it spawned a multimedia franchise, recognized by Guinness World Records as the longest-running film franchise in history, that established the kaiju and tokusatsu genres. It helped Honda gain international recognition and led him to direct numerous tokusatsu films that are still studied and watched today.[10][11]

After directing his eighth and final Godzilla film in 1975, Honda retired from filmmaking.[12] However, Honda's former colleague and friend, Akira Kurosawa, would persuade him to come out of retirement in the late 1970s and act as his right-hand man for his last five films.[7]

Early life

[edit]Childhood and youth (1911–1921)

[edit]

Honda was born in Asahi, Yamagata Prefecture (now part of the city of Tsuruoka),[13][14][15] the fifth and youngest child of Hokan and Miyo Honda. His father Hokan was the abbot of Honda Ryuden-in temple.[13] Honda stated that his forename was a combination derived from three words: "'I' stands for inoshishi, the boar, the astrological symbol of my birth year. shi stands for the number four, the fourth son. And ro indicates a boy’s name. Literally, it means the fourth son, born in the year of the boar."[3][16] He had three brothers: Takamoto, Ryokichi, Ryuzo, and one sister: Tomi, who died during her childhood.[17] Honda's father and grandfather were both Buddhist monks at Churen-ji, a temple in Mount Yudono, where the Hondas lived in a dwelling on the temple's property. The Hondas grew rice, potatoes, daikon radishes, and carrots, and also made and sold miso and soy sauce. The family also received income from a silk moth farm managed by one of Honda's brothers. Honda's father earned income during the summers by selling devotions in Iwate Prefecture, Akita Prefecture, and Hokkaido and would return home before the winter.[16]

While Honda's brothers were given religious tutoring at sixteen, Honda was learning about science.[16] Takamoto, who became a military doctor, encouraged Honda to study and sent him scientific magazines to help, which started Honda's love for reading and scientific curiosity.[18] In 1921, when Honda was ten, Hokan became the abbot at Io-ji temple in Tokyo,[13] and the family moved into the Takaido neighborhood in Suginami. Though he was an honors student back home, Honda's grades declined in Tokyo and in middle school; he struggled with subjects involving equations such as chemistry, biology, and algebra.[19]

After his father transferred to another temple, Honda enrolled in the Tachibana Elementary school in Kawasaki and later in Kogyokusha Junior High where Honda studied kendo, archery, and athletic swimming but quit after tearing his Achilles tendon.[20]

Film education (1931–1934)

[edit]Honda became interested in films when he and his class-mates were assembled to watch one of the Universal Bluebird photoplays. Honda would often sneak into movie theatres without his parents' permission. For silent films in Japan at that time, on-screen texts were replaced with benshi, narrators who stood beside the screen and provided live commentary, which Honda found more fascinating than the films themselves.[21] Honda's brother, Takamoto, had hoped for Honda to become a dentist and join his clinic in Tokyo but instead, Honda applied at Nihon University for their art department's film major program and was accepted in 1931.[22] The film department was a pilot program, which resulted in disorganized poor conditions for the class and cancellations from the teacher every so often. While this forced other students to quit, Honda instead used the cancelled periods to watch films at theaters, where he took personal notes.[23]

Honda and four of his class-mates rented a room in Shinbashi, a few kilometers from their university, where they would gather after school to discuss films. Honda had hoped for the group to collaborate on a screenplay but they mainly just socialized and drank. Honda attended a salon of film critics and students but hardly participated, preferring rather to listen.[23] While in school, Honda met Iwao Mori, an executive in charge of production for Photographic Chemical Laboratories (P.C.L.) In August 1933, Mori offered entry-level jobs at P.C.L. to a few students, including Honda.[11] Honda eventually completed his studies while working at the studio and became an assistant director, which required him to be a scripter in the editing department. Honda eventually became a third assistant director on Sotoji Kimura's The Elderly Commoner's Life Study (1934). However, Honda then received a draft notice from the military.[24]

Military service and marriage (1934–1946)

[edit]

At twenty-three years old, Honda was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army in the fall of 1934. Despite receiving a passing grade on his physical examination, he was not required to report for immediate duty. While waiting for his call-up, Honda continued working at P.C.L. Honda was then called to duty in January 1935 and was enlisted into the First Division, First Infantry Regiment in Tokyo. At the time, Honda began his training at the entry-level rank of Ippeisotsu, the equivalent of Petty Officer First Class.[25]

In 1936, Honda's former commanding officer, Yasuhide Kurihara, launched a coup against the civilian government, what would be called the February 26 Incident. Though Honda had no involvement with the coup, everyone associated with Kurihara were considered dangerous and the brass wanted them gone and as a result, Honda and his regiment were sent to Manchukuo in 1936, under questionable pretense. Honda would have completed his 18 remaining months of service had it not been for the coup and would be recalled to service again and again for the remainder of the war.[26]

Honda met Kimi Yamazaki in 1937 and proposed marriage to her in 1939. Honda's parents and Kimi's mother were supportive, but Kimi's father was opposed to the sudden engagement. Though Kimi's father never approved of her marriage, he nonetheless sent her ¥1,000 upon learning of her pregnancy. Rather than having a traditional wedding ceremony, the two simply signed papers at city hall, paid their respects at Meiji Shrine, and went home.[27] Since their marriage, the couple lived in Seijo in Setagaya, even after the war.[28] Kimi would pass away on November 3, 2018, aged 101. This was also Godzilla's 64th anniversary.[29]

Honda was recalled to service in mid-December 1939, a week before his daughter, Takako, was due to be born.[30] Having already risen in rank, Honda was able to visit his wife and daughter in the hospital but had to leave afterwards immediately to China.[31] Between 1940 and 1941, Honda was assigned to manage a "comfort station", a euphemism for brothels established in occupied areas. Honda would later write an essay titled Reflections of an Officer in Charge of Comfort Women published in Movie Art Magazine in April 1966, detailing his experiences and other comfort women's experiences working in comfort stations.[32]

Honda would then return home in December 1942, only to find that P.C.L. (now rebranded as Toho by that point) were forced to produce propaganda films to support the war effort. The government took control of the Japanese film industry in 1939, modeling the passage of motion picture laws after Nazi policies where scripts and films were reviewed so they supported the war effort and filmmakers noncompliant were punished or worse.[33] Honda's son, Ryuji, was born on 31 January 1944, however, Honda received another draft notice in March 1944. He was assigned to head for the Philippines but his unit missed the boat and were sent back to China instead. To Honda's fortune, the conflict in China was less intense than it was in the Pacific and South-East Asia. Honda became a sergeant and was in charge of trading and communicating with civilians. Honda never ordered the Chinese as a soldier and was respectful to them as much as possible.[34]

Honda was eventually captured by the Chinese National Revolutionary Army and relocated to an area between Beijing and Shanghai for a year before the war ended. During his imprisonment, Honda stated to have been treated well and was even befriended by the locals and temple monks, who offered him to stay permanently but Honda respectfully refused in favor of finding his wife and children. As a parting gift, the locals gave Honda rubbings of Chinese proverbs, imprinted from stone carvings of temples. Honda would later write these verses in the back of his screenplays.[35]

During his final tour, Honda escaped death near Hankou when a mortar shell landed before him but did not detonate. When the battle ended, Honda later returned to retrieve the shell and took it back home to Japan where he placed it on top of his desk in his private study until his death.[36] Honda then returned home in March 1946; however, throughout most of his life, even as an old man, Honda would have nightmares about the war twice or thrice a year.[37] During his entire military service, Honda served three tours, with a total of six years serving at the front.[38]

Career

[edit]1940s

[edit]

Honda returned to work at Toho as an assistant director. In 1946, he worked on two films: Motoyoshi Oda's Eleven Girl Students and Kunio Watanabe's Declaration of Love. In 1947, he worked on three films, 24 Hours in an Underground Market (jointly directed by Tadashi Imai, Hideo Sekigawa, and Kiyoshi Kusuda) and The New Age of Fools Parts One and Two, directed by Kajirō Yamamoto.[39] Due to a labor dispute at Toho, many stars and employees split off and formed Shintoho. Kunio Watanabe tried to convince Honda to join Shintoho, with the promise of Honda becoming a director quicker, however, Honda chose to remain neutral and stayed at Toho.[40] Despite struggling at Toho, Honda worked on a handful of films produced by Film Arts Associates Productions.[39] Between September and October 1948, Honda was on location in Noto Peninsula working on Kajirō Yamamoto's Child of the Wind, the first release from Film Arts. From January to March 1949, Honda worked with Yamamoto again on Flirtation in Spring.[39]

Prior to being promoted to a feature film director, Honda had to direct documentaries for Toho's Educational Films Division. Toho sometimes used documentary projects as tests for assistant directors due to become directors.[41] Honda's directorial debut was the documentary Ise-Shima, a twenty-minute highlight reel of Ise-Shima's cultural attractions. It was commissioned by local officials to boost tourism to the national park. The film covers a brief history of the Ise Grand Shrine, the local people, the economy, and pearl farms.[41] The film is also notable for being the first Japanese film to utilize underwater photography successfully. Honda originally wanted to use a small submarine-like craft but the idea was scrapped due to budget and safety concerns. Instead, professional divers assisted with the production. Honda had commissioned a camera technician colleague who designed and built an air-tight, waterproof, metal-and-glass housing for a compact 35-millimeter camera.[42] The documentary was completed in July 1949 and became a triumph for Toho. The documentary was then sold to multiple European territories. It disappeared for a long time until it resurfaced on Japanese cable television in 2003. Between July and September 1949, shortly after finishing Ise-Shima, Honda reunited with his friend Akira Kurosawa on Stray Dog and began working as a chief assistant director on the film.[43] Honda mainly directed second unit photography, all of the footage pleased Kurosawa and has stated to "owe a great deal" to Honda for capturing the film's post-war atmosphere.[43]

1950s

[edit]In 1950, Honda worked on two films by Kajirō Yamamoto: Escape from Prison and Elegy, the last film produced by Film Art Associations.[44] Honda had also worked as an assistant director on Senkichi Taniguchi's Escape at Dawn.[45][b]

Between working on films as an assistant director, Honda began pre-production on Newspaper Kid, which would have been his feature directorial debut. However, the project was canceled. Instead, he began working on another documentary titled Story of a Co-op (also known as Flowers Blooming in the Sand and Co-op Way of Life)[44][46] Story of a Co-op was a documentary about the rise of consumer cooperatives in post-war Japan. It was also written by Honda, with the production overseen by Jin Usami and with the support of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Some records indicated that some animation was used to explain the functions of co-ops but these reports have been unconfirmed. The film was completed on 6 October 1950 and has since been lost. However, Honda recalled that the film was successful enough to convince Toho to assign Honda his first feature film.[47]

Between filming the documentaries, Toho had offered Honda the chance to develop and direct a war film titled Kamikaze Special Attack Troop. Toho then chose not to proceed with the project after finding Honda's script, which openly criticized leaders of World War II, to be too grim and realistic. Honda recalled that the studio felt it was "too soon after the war" to produce such a film. Had the project proceeded, it would have been Honda's first directorial feature. The script has since been lost.[48]

At the age of 40, Honda completed his first feature film The Blue Pearl.[2][11][12] Released on 3 August 1951, it was one of the first Japanese feature films to utilize underwater photography and the first studio film to be shot in the Ise-Shima region.[49][50]

Honda initially chose not to direct war films, but changed his mind after Toho offered to have him direct Eagle of the Pacific, a film about Isoroku Yamamoto, a figure with whom Honda shared the same feelings regarding the war. It was the first film where Honda collaborated with Eiji Tsuburaya.[51] Eagle of the Pacific was a box-office hit and reportedly was Toho's first postwar film to earn over ¥100 million (approximately $278,000).[51] Subsequently, Honda would direct another war film, entitled Farewell Rabaul, which was released on February 10, 1954.[52]

A month after the release of Farewell Rabaul, Honda met assistant director Kōji Kajita to commence production on a film titled Sanshiro the Priest. Possibly connected to Kurosawa's 1943 film Sanshiro Sugata; Hideo Oguni, one of Kurosawa's frequent collaborators, wrote the script for the film. Authors Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski stated that the project never came to fruition because Oguni and Honda "couldn't see eye to eye about the screenplay".[53] According to Kajita, the film would have been about a priest and a judo expert.[53]

Following the cancellation of a highly anticipated drama film titled In the Shadow of Glory, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka quickly converted the idea of a giant monster film. He was influenced by reports of a nuclear test in the Pacific that caused a Japanese fishing boat to be exposed to nuclear fallout, with disastrous results, and had heard of a recently released American monster film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.[54][c] Honda accepted the offer to direct the film after planned In the Shadow of Glory director Taniguchi declined the assignment.[56][57][54] Honda and screenwriter Takeo Murata confined themselves in a three-week secluded residence at an inn in Tokyo's Shibuya ward to write the screenplay for this film, entitled Godzilla.[58] The film was Honda's first kaiju film, the genre for which he would become most famous. The simple story, about a giant monster that rises near Odo Island and attacks Tokyo causing catastrophic destruction, is a metaphor for a nuclear holocaust.

Principal photography for Godzilla began on August 2, 1954,[59] and wrapped in late September,[60] taking 51 days.[61] It became a box office success in Japan and was nominated for two Japanese Movie Association awards: winning an award for best special effects[62] but losing to Kurosawa's Seven Samurai for best picture.[63] Because of the film's success in Japan, it spawned a multimedia franchise, being recognized by Guinness World Records as the longest-running film franchise in history.[64] Two years later, a heavily localized version of Godzilla was released in the United States as Godzilla, King of the Monsters!.[65]

Honda's next film was Lovetide, based on Hidemi Kon's story Blow, River Wind and adapted by screenwriter Dai Nishijima. Toho promoted the film by calling it a "gorgeous love melodrama with Toho's best cast, meant for all the woman fans".[66] The film's stars Mariko Okada and Chieko Nakakita (Tanaka's wife) also played in Mikio Naruse's film Floating Clouds, featuring a similar plot and released around a week after Lovetide.[67] Tanaka had stated that if he had not made Honda predominantly direct science-fiction films, he would have become "a director like Mikio Naruse."[67]

During the start of production on Motoyoshi Oda's Godzilla Raids Again, Honda began filming Half Human in the Japanese Alps.[68] Upon his return to Tokyo, Tsuburaya was working on Godzilla Raids Again. Thus, production on Half Human was halted and Honda moved on to shooting a drama film titled Mother and Son. Principal photography for Half Human recommenced in June, and the film was released on August 14, 1955, around a month after filming concluded.[69][68] Half Human has been infrequently seen following its release. Ryfle and Godziszewski noted this is possibly due to Toho fearing the mountain tribe, described by Nobuo Nakamura's character as "mysterious buraku", is depicted in the film as "an uncivilized, primitive colony of subhuman freaks", could enrage burakumin's rights groups such as the Buraku Liberation League.[70] Some sources suggest it was aired on television in the 1960s or early 1970s and was screened at a film retrospective in Kyoto in 2001.[71] Toho has never released the complete film in any home video format.[71]

In 1956, Honda directed four films. The first, Young Tree, concerns a young girl who moves to Tokyo and endures the rivalries between other high school girls of varying economic and cultural backgrounds.[72] The second, entitled Night School, was his solo film ever directed outside of Toho and was among the first films about night schooling.[73] The third, titled People of Tokyo, Goodbye, follows young lovers who try to listen to their hearts despite their parents' interjections.[74] The fourth, Rodan, was Honda's first-ever film shot in color and depicted a winged monster named Rodan wreaking havoc in Japan after its awakening by nuclear bomb testing.[75]

Although Japanese cinema is known for its samurai films, Honda did not show any interest in directing a jidaigeki film since his stage was contemporary Japan.[76] Nonetheless, in May 1956, Kurosawa reported that he would produce three jidaigeki films beginning that September, with Honda directing Throne of Blood, Hideo Suzuki directing The Hidden Fortress, and Hiromichi Horikawa directing Revenge (became Yojimbo).[77] Kurosawa would eventually direct all three of these films;[76] now regarded as some of his best films.[78][79]

The year 1957 marked a turning point in Honda's directing career, as he directed five films, with his first, Be Happy, These Two Lovers, filmed by Hajime Koizumi, who would work on 21 of his films thereon.[80] Ryfle and Godziszewski called his camera work "the perfect complement to Honda's conservative, risk-averse style of composition".[80]

His next film, A Teapicker's Song of Goodbye, was the second in Honda's trilogy of films starring enka singer Chiyoko Shimakura (the first film was People of Tokyo, Goodbye). The third film in the trilogy, entitled A Farewell to the Woman Called My Sister, was released the month after A Teapicker's Song of Goodbye.[81] A Rainbow Plays in My Heart, a black-and-white two-part film based on Seiichi Yashiro and Ryunosuke Yamada's[82] radio drama of the same name, was released on July 9, 1957 (a week after A Teapicker's Song of Goodbye).[83] The film is notable for being the third and final film featuring Godzilla stars Momoko Kochi and Akira Takarada in leading roles.[83]

Honda's only tokusatsu film of 1957, The Mysterians, was released just over a year after Japan joined the United Nations and features affairs reflecting the Japan's return to global politics.[84] The story concerned a young scientist (Kenji Sahara) who becomes involved in a globally threatening alien invasion. The film was shot on an enormous budget of ¥200 million and was his debut movie to be filmed in Toho Scope.[85]

Song for a Bride, released in February 1958, is regarded as one of the director's best films of the 1950s.[86] It is a comedy-drama film that explores the clash between traditional and modern ethics among Japanese youth.[87] Following its release, Honda would direct two science fiction films in the same year for the first time. His second film of 1958, The H-Man, premiered on June 24, 1958 to mixed reviews. It is a distinctive Honda picture about a liquid creature who terrorizes Tokyo's gangland. Some scenes in the film were shot on the same sets used in Kurosawa's 1948 film Drunken Angel. In May 1959, Columbia Pictures released a shortened version of this film in the United States. Upon its release, U.S. critics erroneously believed it was a rip-off Irvin Yeaworth's The Blob, despite The H-Man being released prior to The Blob in Japan.[88]

The successful distributions of Honda's Godzilla and Rodan in the United States, lead Toho to seek further Hollywood connections.[89] In 1957, the company agreed to co-produce a made-for-television film with AB-PT Pictures (who would go bankrupt during production).[90] This project would eventually become a black-and-white theatrical feature film directed by Honda, entitled Varan the Unbelievable, released in 1958.[91] Considered his "weakest effort",[92] it is a simple story about scientists who unintentionally awake a giant monster dubbed Varan while seeking scarce species of butterfly in Tōhoku region.

An Echo Calls You, his twenty-third feature film, centers on an uneducated bus conductor, Tamako, who falls in love with Nabeyama, her bus driver after she fails to have a relationship with a man from Kōfu's wealthiest family. Featuring Ryō Ikebe in his fourth major role in a Honda movie, and with a possibly Hideko the Bus Conductor-inspired screenplay by Gorō Tanada, the film premiered in January 1959 to generally positive reviews from critics.[93][94]

Honda quickly moved on to his next project, Inao, Story of an Iron Arm. It is a biographical film based on the life of professional baseball pitcher Kazuhisa Inao, featuring Inao portraying himself as an adult. Additionally, it features Godzilla actors Takashi Shimura as his father and Ren Yamamoto and Sachio Sakai as his older brothers. The film was released in March 1959 and was later screened in honor of Inao following his death in 2007.[95]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

In 1962, Honda returned to directing Godzilla films beginning with King Kong vs. Godzilla. Honda would go on to direct five additional Godzilla films during the 1960s: Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964), Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), Destroy All Monsters (1968), and All Monsters Attack (1969), the latter which Honda also served as director of special effects. His other tokusatsu films during the 1960s include: Mothra (1961), Matango (1963), Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965), The War of the Gargantuas (1966), and King Kong Escapes (1967). While Honda managed to retain a job directing for Toho during the 1960s and 1970s, the studio did not renew his contract near the end of 1965 and was instructed to speak with Tanaka about employment on a film-by-film basis.[96] In 1967, Honda began occasionally directing for television, since it had become more popular than the film industry in Japan.[97]

Between 1971 and 1973, Honda directed several episodes for the television series Return of Ultraman, Mirrorman, Emergency Command 10-4, 10-10, Thunder Mask, and Zone Fighter,[98] and would only direct two films during the 1970s: Space Amoeba (1970) and Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975); Honda would temporarily retire following the release of the latter film.[12]

Final works and last years (1979–1993)

[edit]Collaborating with Akira Kurosawa (1979–1992)

[edit]Despite retiring in 1975, Honda was persuaded by Akira Kurosawa to return to filmmaking, and collaborate on Kagemusha (1980). Honda would subsequently work on Kurosawa's last five films. His positions in these films included: directorial advisor, production coordinator, and creative consultant; he also made uncredited writing contributions to Madadayo (1993).[99] There is a common misconception that Honda directed three sequences of Kurosawa's 1990 film Dreams entitled "The Tunnel,"[100] "Mount Fuji in Red," and "The Weeping Demon."[101] In the early 1980s, Honda was approached to potentially direct a reboot of Daimajin reboot. While Honda expressed interest, the project never materialized and Honda was already involved with Kagemusha.[102][103]

Declining health and death (1992–1993)

[edit]Honda was truly a virtuous, sincere, and gentle soul. He worked for the world of film with might and main, lived a full life and very much like his nature, quietly exited this world.

— Inscription on Honda's headstone by Akira Kurosawa.[104]

In late 1992, Akira Kurosawa hosted a party for the cast and crew of Madadayo following the completion of principal photography. Honda appeared to be suffering from cold symptoms at the party and contacted his son Ryuji in New York. Ryuji believed Honda was drunk and thought it strange that he called him.[105] Then, in mid-February 1993, Kurosawa, Honda, and Masahiko Kumada, the unit manager, attended a screening of Agantuk, Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray's last film, at an art-house cinema.[105] After watching the film, Kurosawa invited Honda to his house for dinner and drinks, but Honda felt sick and went home. Honda was declared healthy following a checkup in December 1992, and no major illnesses were suspected. Although his cough kept getting worse, his family doctor diagnosed him with a common cold.[106] Initially, Honda stayed in bed for a week, but after he lost his appetite, he underwent X-rays and blood tests. Honda was immediately told to seek hospital treatment following the results. Knowing something was wrong with his health, Honda had already packed his bags. Within ten minutes of leaving home, he was taken to Kono Medical Clinic, a 19-bed facility in Soshigaya. Because the major hospitals were full, he was placed in a tiny room.[106]

A room in a bigger hospital was about to be assigned to Honda, so his friends could visit him. In the following days, Honda contracted pleurisy, a condition that causes difficulty breathing, and on February 27, just after returning home from visiting hours, Kimi and Takako received an urgent call: his vital signs had suddenly deteriorated.[106] Honda died from respiratory failure at 11:30 pm on February 28, 1993.[107][108] A memorial service was held at Joshoji Kaikan, an assembly hall in Setagaya, for Honda's friends, family, and colleagues on March 6.[109] Honda's funeral reunited Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, an actor who had starred in both Honda's and Kurosawa's early films. The Nikkei reported that Mifune was among the mourners at the funeral: "[Kurosawa and Mifune] made eye contact and hugged in tears at the funeral for their mutual friend."[110]

Honda's cremated remains were buried at Tama Cemetery, the largest municipal cemetery in Japan. His family later moved the grave to Fuji Cemetery.[104]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]Director

[edit]Miscellaneous

[edit]| Year | Title | Assistant director | Actor | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | The Elderly Commoner's Life Study | Yes | No | 3rd assistant director | [9] |

| 1935 | Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts | Yes | No | 2nd assistant director | [25] |

| 1937 | A Husband's Chastity | Yes | No | With Akira Kurosawa | [155] |

| Nadare | Yes | No | With Akira Kurosawa | [156] | |

| Enoken's Chakiri Kinta Part 1 | Yes | No | 2nd assistant director | [156] | |

| Enoken's Chakiri Kinta Part 2 | Yes | No | With Akira Kurosawa | [157] | |

| Humanity and Paper Balloons | Yes | No | [158] | ||

| 1938 | Chinetsu | Yes | No | With Akira Kurosawa | [159] |

| Tojuro no koi | Yes | No | With Akira Kurosawa | [160] | |

| Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro | Yes | No | 3rd assistant director | [158] | |

| Chocolate and Soldiers | Yes | No | Chief assistant director | [161] | |

| 1941 | Uma | Yes | No | With Hiromichi Horikawa | [162] |

| 1944 | Colonel Kato's Falcon Squadron | Yes | No | [163] | |

| 1946 | Eleven Girl Students | Yes | No | [40] | |

| Declaration of Love | Yes | No | [40] | ||

| 1947 | 24 Hours in an Underground Market | Yes | No | [15] | |

| The New Age of Fools | Yes | No | [39] | ||

| Spring Banquet | Yes | No | [15] | ||

| 1949 | Child of the Wind | Yes | No | [39] | |

| Flirtation in Spring | Yes | No | [39] | ||

| Stray Dog | Yes | No | Chief assistant director | [164] | |

| 1950 | Escape at Dawn | Yes | No | [45] | |

| Escape from Prison | Yes | No | [44] | ||

| 1951 | Elegy | Yes | No | [44] | |

| 1966 | Ebirah, Horror of the Deep | No | No | Editor; Toho Champion Festival re-release | [165] |

| 1967 | Son of Godzilla | No | No | Editor; Toho Champion Festival re-release | [165] |

| 1980 | Kagemusha | No | No | Production coordinator 2nd unit director |

[166] |

| 1985 | Ran | No | No | Director Counsellor | [167] |

| 1986 | Toho Unused Special Effects Complete Collection |

No | No | Interviewee | [15] |

| 1987 | The Drifting Classroom | No | Yes | Grandfather | [168] |

| Come Back Hero | No | Yes | Priest at wedding ceremony | [100] | |

| 1988 | The Discarnates | No | Yes | Street vendor | [168] |

| 1990 | Dreams | No | No | Creative consultant | [169] |

| 1991 | Rhapsody in August | No | No | Associate director | [170] |

| 1993 | Madadayo | No | No | Directorial Adviser and co-writer | [99] |

| Samurai Kids | No | Yes | Deceased grandfather [portrait; posthumous] | [168] | |

| 1994 | Turning Point | No | Yes | Photograph; posthumous | [171] |

| 1996 | Rebirth of Mothra | No | Yes | Photograph; posthumous | [15] |

Television

[edit]| Airdate | Episode | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Newlyweds (Shinkon san) | |||

| 7 January 1967 | "The Woman, at That Moment" ("Onna wa sono toki") | [172] | |

| 7 February 1967 | "Forgive Me Please, Mom" ("Yurushitene okasan") | ||

| Husbands, Men, Be Strong (Otto yo otoko yo tsuyokunare) | |||

| 9 October 1969 | "Honey, It's a Presidential Order" ("Anata shacho meirei yo") | [172] | |

| 30 October 1969 | "We're Going South-Southwest" ("Nan nan sei ni ikuno yo") | ||

| Return of Ultraman | |||

| 2 April 1971 | "All Monsters Attack" | [173] | |

| 9 April 1971 | "Takkong's Great Counterattack" | ||

| 14 May 1971 | "Operation Monster Rainbow" | ||

| 28 May 1971 | "Monster Island S.O.S." | ||

| 31 March 1972 | "The Five Oaths of Ultra" | ||

| Mirrorman | |||

| 5 December 1971 | "Birth of Mirrorman" ("Miraman tanjo") | [172] | |

| 12 December 1971 | "The Intruder is Here" ("Shinryakusha wa koko ni iru") | ||

| Emergency Command 10-4, 10-10 (Kinkyu shirei 10-4, 10-10) | |||

| 31 July 1972 | "Japanese Beetle Murder Incident" ("Kabutomushi satsujin jiken") | [172] | |

| 7 August 1972 | "Vampire of the Amazon" ("Amazon no kyuketsuki") | ||

| 13 November 1972 | "Assassin from Outer Space" ("Uchu kara kita ansatsuha") | ||

| 20 November 1972 | "Attack of Monster Bird Ragon" ("Kaicho Ragon no shugeki!") | ||

| Thunder Mask | |||

| 3 October 1972 | "Look! The Double Transformation of the Akatsuki" ("Miyo! Akatsuki no nidan henshin") | [174] | |

| 10 October 1972 | "The Boy Who Could Control Monsters" ("Maju wo ayatsuru shonen") | ||

| 21 October 1972 | "Devil Freezing Strategy" ("Mao reito sakusen") | ||

| 28 October 1972 | "Merman's Revenge" ("Kyuketsu hankyojin no fukushu") | ||

| 2 January 1973 | "Monster Summoning Smoke" ("Maju wo yobu kemuri") | ||

| 9 January 1973 | "Degon H: Death Siren" ("Shi no kiteki da degon H") | ||

| Zone Fighter | |||

| 16 April 1973 | "Defeat Garoga's Subterranean Base!" ("Tatake! Garoga no chitei kichi") | [172] | |

| 23 April 1973 | "Onslaught! The Garoga Army: Enter Godzilla" ("Raishu! Garoga daiguntai-Gojira toujo") | ||

| 18 June 1973 | "Terrobeat HQ: Invade the Earth!" ("Kyoju kichi chikyu e shinnyu!") | ||

| 25 June 1973 | "Absolute Terror: Birthday of Horror!" ("Senritsu! Tanjobi no kyofu") | ||

| 30 July 1973 | "Mission: Blast the Japan Islands" ("Shirei: Nihon retto bakuha seyo") | ||

| 6 August 1973 | "Order: Destroy Earth with Comet K" ("Meirei: K susei de chikyu wo kowase") | ||

| 3 September 1973 | "Secret of Bakugon, the Giant Terro-Beast" ("Daikyouju Bakugon no himitsu") | ||

| 10 September 1973 | "Smash the Pin-Spitting Needlar" ("Hari fuki Nidora wo taose") | ||

Style

[edit]Despite being known primarily for directing tokusatsu films, Honda has also directed documentaries, melodramas, romance, musical, and biographical films. Unlike Akira Kurosawa, who often used recurring themes and photographic devices (even sometimes going over time and budget on productions), Honda was a filmmaker who almost always finished his projects requested by Toho on time and budget; Godzilla (1954) was one such project.[175] Godzilla assistant director Kōji Kajita stated that during their 17 films that they made together Honda "had his own style, this way of thinking", adding: "he never got mad, didn’t rush, but he still expressed his thoughts and made it clear when something was different from what he wanted, and he corrected things quietly."[176] Thus, his skill earned him the nickname "Honda the Amylase".[175]

Direction

[edit]Authors, cast, and crew members have called Honda's style of direction "well-established".[177][178] Special effects director Teruyoshi Nakano stated that the events happening during his "running crowd" sequences, such as "Firefighters being dispatched in an emergency situation, police officer directing traffic, and people carrying furoshiki while running away", are "unrealistic" but it was important for Honda to "bring out the everydayness by showing such things".[177] According to actor Yoshio Tsuchiya, Kurosawa said that if he were to direct a scene in one of Honda's films featuring police officers directing civilians, he would "make even the police officers flee first."[179] Regarding this, Honda said that the policemen featured in his films do not run away because of his war experience as an officer.[180] Hiroshi Koizumi said that, during the filming of Mothra, Honda was focusing to appear in a scene where a civilian helped the baby on the bridge.[181]

Legacy

[edit]Reputation in the film industry

[edit]Many filmmakers have been influenced by Honda's work. According to Steve Ryfle, his influence inside the film industry is "undeniable", as he was "one of the creators of the modern disaster film, he helped set the template for countless blockbusters to follow, and a wide array of filmmakers".[7] In 2007, Quentin Tarantino called Honda his "favorite science-fiction director".[182] Tarantino is also one of several filmmakers and actors who have cited Honda's The War of the Gargantuas as an influence,[183] alongside Brad Pitt,[7][184] Guillermo del Toro,[185] and Tim Burton.[185] John Carpenter cited Godzilla as an influence on his career and called Honda "one of my personal cinematic gods".[186] Martin Scorsese has also cited Honda as an influence on his work.[7]

In popular culture

[edit]The episode, "Tagumo Attacks!!!" in the television series Legends of Tomorrow is based around Honda. The central plotline of the episode involves a kraken-esque creature named Tagumo, that Honda has written, which becomes a reality due to a magic book that belongs to Brigid, the Celtic goddess of art. It is described as a "land octopus" that will destroy Tokyo, unless the protagonists can stop it. At the end of the episode, the character, Mick Rory tells Ishirō to "Forget about the octopus. Lizards. Lizards are king." In this fictional universe, this will lead Ishirō to creating the character Godzilla, as he states in the episode "The King... of the Monsters. I like that".[187] Honda, alongside Ray Harryhausen, was given dedications in the 2013 film Pacific Rim.[188]

In his acclaimed 2023 film Godzilla Minus One, filmmaker and visual effects artist Takashi Yamazaki paid homage to Honda's work.[189]

Lawsuit and dispute

[edit]In October 2011, Honda's family began suing Toho and three other companies involved in the 2010 pachinko game CR Godzilla: Descent of the Destruction God, requesting ¥127 million.[190][191] On November 26, 2013, it was disclosed that the lawsuit had been settled. An industry insider suggested that Toho wanted the lawsuit dealt with before the release of Godzilla (2014).[191]

Conflict between Toho and Honda Film Inc.—the company led by Honda's son Ryuji—had been ongoing since February 2010 when Ryuji sent a letter to Toho saying that the family beileved it unfair that Toho claimed "Honda does not have any rights to the Godzilla character" and requested that they oversee and authorize all projects involving the character henceforth. Toho dismissed his claim as unnecessary, stating that they "have never received any objections" from Honda nor his widow Kimi regarding Godzilla's copyright ownership. Talks between the two companies reportedly escalated thereafter. On May 14, 2010, Toho argued that Tanaka and Shigeru Kayama had a larger role in the creation of the character, alleging that both of whom had agreed that Toho is the copyright owner. Honda Film responded on April 23 by stating Honda nevertheless directed and co-wrote the original film and thus was responsible for the creature's "visual aspects", adding: "As director and screenwriter, Director Honda determined the internal character setting of Godzilla, such as his history and personality, that appears in Godzilla, and expressed it concretely. Therefore, Director Honda is the author of Godzilla (as a character)". Honda's family eventually extracted their ownership claims in October 2011, shortly before the pachinko lawsuit started.[190]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Honda's given name has often been misread as "Inoshirō" (Japanese: いのしろう, Hepburn: Inoshirō) because his parents only used the letter I from the kanji character for Inoshishi (Japanese: 猪, lit. 'wild boar').[3][4] He is also known by the nicknames Ino-san (いのさん, Ino-san, lit. 'Piggy') and Inoshirō-san (いのしろさん) in Japan.[3] Additionally, some Japanese sources have erroneously written his surname as 本田, instead of 本多.[5]

- ^ According to a copy of the screenplay found in Honda's archives, Honda served as assistant director, even though he is not listed in the credits for Escape at Dawn.[46]

- ^ The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms opened in Japan a few weeks after Godzilla. Japanese critics regarded Godzilla as superior.[55]

References

[edit]- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 31.

- ^ a b Takaki et al. 1999, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b c Honda, Yamamoto & Masuda 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Nakajima, Shinsuke (7 May 2013). "イシロウ、それともイノシロウ?". IshiroHonda.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Some of these sources include:

- Kikuchi 1954, p. 321

- Akiyama 1974, p. 194

- The Asahi Shimbun Company 1990, p. 62

- Takiguchi & Ōoka 1991, p. 15

- Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art 1995, p. 112

- Matsuda 1999, p. 43

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. xiv.

- ^ a b c d e Ryfle, Steve (24 October 2019). "Godzilla's Conscience: The Monstrous Humanism of Ishiro Honda". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. xv.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (18 November 2017). "Ishiro Honda: The master behind Godzilla". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Tanaka 1983, pp. 539–540.

- ^ a b c Iwabatake 1994, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b c Honda, Yamamoto & Masuda 2010, p. 250.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "Biography". IshiroHonda.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 9–11.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 15.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 164.

- ^ "Ishiro Honda's Wife Passes Away at 101". Godzilla-Movies.com. 6 November 2018. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 33–40.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 47.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 49.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 51.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 307.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 70.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 53.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 59.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 72.

- ^ Iwabatake 1994, p. 51.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 84.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 104.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2006, 00:05:50.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2006, 00:06:05.

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Ōtomo 1967.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 36.

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 31.

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Higgins, Bill (30 May 2019). "Hollywood Flashback: Godzilla First Set Off on a Path to Destruction in 1954". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Jennifer Lawrence, Game of Thrones, Frozen among new entertainment record holders in Guinness World Records 2015 book". Guinness World Records. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 148.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 108.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 109.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 114.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 113.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 117.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 119.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 124.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 126.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 130.

- ^ Hamano 2009, p. 684.

- ^ Waldstein, Howard (16 May 2022). "10 Best Akira Kurosawa Films, Ranked". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Kantor, Jonathan H. (27 August 2022). "Every Akira Kurosawa Movie Ranked Worst To Best". Looper. Static Media. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 132.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Galbraith IV 2008, p. 134.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 135.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 138.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 142.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 144.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 144–147.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Kalat 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 149.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 152–154, 301.

- ^ a b Galbraith IV 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 230.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 237.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 302–303.

- ^ a b Galbraith IV 2008, p. 382.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 287.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 356.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 285.

- ^ Sloss, Steven (16 May 2023). "Idol Threat: Daimajin's Colossal Cultural Footprint". Arrow Films. Archived from the original on 20 November 2024. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 294.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 292.

- ^ Yomiuri Shimbun 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 293.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2002, p. 637.

- ^ a b c Phillips & Stringer 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 96.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Nollen 2019, p. 196.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 108.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 136.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 149.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 176.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 183.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 190.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 194.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 194.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 206.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 210.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 215.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 221.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 225.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 231.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 251.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 258.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 281.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 300.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Galbraith IV 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 24.

- ^ "馬". Toho (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Tanaka 1983, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 263.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 322.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 343.

- ^ a b c Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 286.

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa's Dream (1990)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Richie 1998, p. 260.

- ^ "女ざかり". National Film Archive of Japan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 302.

- ^ Mill Creek Entertainment 2020, p. 8-19.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 303.

- ^ a b Nakamura et al. 2014, p. 81.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 2017.

- ^ a b Kabuki 1998, pp. 338–340.

- ^ Sakai & Akita 1998, p. 178.

- ^ Iwabatake 1994, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Toho Publishing Business Office 1986, pp. 158–167.

- ^ Yosensha 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Fazio, Giovanni (16 August 2007). "Quentin Tarantino: a B-movie badass". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 235.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, pp. 231, 313.

- ^ a b Konrad, Jeremy (26 March 2022). "The War Of The Gargantuas On Preorder At Waxwork Records". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Ishiro Honda". Wesleyan University Press. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Tagumo Attacks!!!". The CW. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Faraci, Devin (1 July 2013). "Guillermo Del Toro On Classic Kaiju And Why Pacific Rim Doesn't Feature Robots". Birth.Movies.Death. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Yonehara, Norihiko (29 October 2023). "ゴジラ映画とは「終われない神事」である 山崎貴監督が語る"神様兼怪物"の本質". AERA dot. (in Japanese). p. 1. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ a b "「ゴジラは誰の物か」泥沼裁判に 本多監督の遺族、東宝を訴える". Livedoor (in Japanese). Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b "「ゴジラ」の著作権裁判が和解". HuffPost (in Japanese). 26 November 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Akiyama, Kuniharu [in Japanese] (1974). 日本の映画音楽史 [History of Japan's film music] (in Japanese). Tabata Shoten.

- Phillips, Alastair; Stringer, Julian, eds. (2007). Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134334223.

- "Asahi Graph: Volumes 3554-3563". Asahi Graph (in Japanese). The Asahi Shimbun Company. 1990.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, Inc. ISBN 978-0-571-19982-2.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1461673743.

- Hamano, Yasuki [in Japanese] (18 December 2009). 大系黒澤明 [The Akira Kurosawa Archives] (in Japanese). Vol. 2. Kodansha. ISBN 9784062155762.

- 被爆 50周年記念展, ヒロシマ以後 現代美術からのメッセージ [50th Anniversary Commemorative Exhibition, After Hiroshima: A Message from Contemporary Art] (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. 1995.

- Honda, Ishirō; Yamamoto, Shingo; Masuda, Yoshikazu (8 December 2010). 「ゴジラ」とわが映画人生 [Godzilla and My Movie Life] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Wanibooks. ISBN 978-4847060274.

- Iwabatake, Toshiaki (September 1994). テレビマガジン特別編集 誕生40周年記念 ゴジラ大全集 [TV Magazine Special Edition 40th Anniversary of the Birth of Godzilla Complete Works] (in Japanese). Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-178417-X.

- Kabuki, Shinichi (1998). ゴジラ映画クロニクル 1954-1998 ゴジラ・デイズ [Godzilla Days: The Godzilla Movie Chronicles 1954~1998] (in Japanese). 集英社. ISBN 4087488152.

- Kalat, David (2010). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series (2nd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 9780786447497.

- Kikuchi, Hiroshi (1954). "Volume 32, Issues 10-11". Bungei Shunjū (in Japanese). Bungeishunjū.

- Matsuda, Ryoichi (9 November 1999). 山田詠美愛の世界 マンガ・恋愛・吉本ばなな [The World of Emi Yamada: Manga/Romance/Banana Yoshimoto] (in Japanese). Tokyo Shoseki. ISBN 978-4-4877-9496-6.

- Mill Creek Entertainment (2020). Return of Ultraman - Information and Episode Guide. Mill Creek Entertainment. ASIN B081KRBMZY.

- Motoyama, Sho; Matsunomoto, Kazuhiro; Asai, Kazuyasu; Suzuki, Nobutaka; Kato, Masashi (2012). 東宝特撮映画大全集 [Toho Special Effects Movie Complete Works] (in Japanese). villagebooks. ISBN 978-4864910132.

- Nakamura, Tetsu; Shiraishi, Masahiko; Aita, Tetsuo; Tomoi, Taketo; Shimazaki, Jun; Maruyama, Takeshi; Shimizu, Toshifumi; Hayakawa, Masaru (29 November 2014). ゴジラ東宝チャンピオンまつりパーフェクション [Godzilla Toho Champion Festival Perfection] (in Japanese). ASCII MEDIA WORKS. ISBN 978-4048669993.

- Nollen, Scott Allen (14 March 2019). Takashi Shimura: Chameleon of Japanese Cinema. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-3569-9.

- Ōtomo, Shōji [in Japanese] (15 May 1967). Kinema Junpo (ed.). 世界怪物怪獣大全集 [The World of Kaibutsu and Kaiju Complete Works] (in Japanese). Kinema Junposha.

- Richie, Donald (1998). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. ISBN 0520220374.

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488.

- Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2006). Gojira Audio Commentary (DVD). Classic Media.

- Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819570871.

- Sakai, Yuto; Akita, Hideo (1998). ゴジラ来襲!! 東宝特撮映画再入門 [Godzilla Attacks!! A re-introduction to Toho tokusatsu films] (in Japanese). KK Longsellers. ISBN 4-8454-0592-X.

- Takaki, Junzo; Matsunomoto, Kazuhiro; Nakamura, Satoshi; Motoyama, Sho; Tsuchiya, Rieko (1999). ゴジラ画報 東宝幻想映画半世紀の歩み [The Godzilla Chronicles] (in Japanese) (3rd ed.). Takeshobo. ISBN 4-8124-0581-5.

- Tanaka, Tomoyuki (1983). 東宝特撮映画全史 [The Complete History of Toho Special Effects Movies] (in Japanese). Toho Publishing Business Office. ISBN 4-924609-00-5.

- Takiguchi, Shūzō; Ōoka, Makoto (1991). コレクション瀧口修造: Yohaku ni kaku I-II [Shūzō Takiguchi's Collection: Yohaku ni kaku I-II] (in Japanese). Misuzu Shobō.

- キングコング対ゴジラ/地球防衛軍 [King Kong vs. Godzilla/Earth Defense Force]. Toho Sci-Fi Tokusatsu Movie Series VOL.5 (in Japanese). Toho Publishing Business Office. 1986. ISBN 4-924609-16-1.

- "「ゴジラ」世に出した監督・本多猪四郎さん死去" [Godzilla director Ishirō Honda has passed away]. Yomiuri Shimbun (in Japanese) (evening ed.). 1 March 1993. p. 19.

- 別冊映画秘宝 モスラ映画大全 [Mothra Movies Complete Collection] (in Japanese). Yosensha. 2011. ISBN 978-4-86248-761-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Eiji Tsuburaya's World of Tokusatsu [円谷英二特撮世界] (in Japanese). Keibunsha. 2001. ISBN 4-7669-3848-8.

- Higuchi, Naofumi (2011). グッドモーニング、ゴジラ 監督本多猪四郎と撮影所の時代 [Good Morning Godzilla: The Golden Age of the Movie Studio and Director Ishiro Honda] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Kokusho Kankokai. ISBN 978-4336054043.

- Honda, Kimi; Nishida, Miyuki (17 December 2012). ゴジラのトランク 〜夫・本多猪四郎の愛情、黒澤明の友情 [Godzilla's Trunk: The Love of Husband Ishiro Honda, the Friendship of Akira Kurosawa] (in Japanese). Takarajimasha. ISBN 978-4800205643.

- Mamiya, Naohiko (2000). ゴジラ1954-1999超全集 [Godzilla 1954-1999 Super Complete Works] (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4091014702.

- Sahara, Kenji (2005). 素晴らしき特撮人生 [A Wonderful Life in Tokusatsu] (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4093875974.

- Takarada, Akira (August 1998). ニッポン・ゴジラ黄金伝説 [Godzilla: The Golden Legend of Japan] (in Japanese). Fusosha Publishing. ISBN 4594025358.

- Takeuchi, Hiroshi (April 2000). 本多猪四郎全仕事 [The Complete Works of Ishiro Honda] (in Japanese). Asahi Sonorama. ISBN 978-4257035923.

- Tsuruta, Yoshihisa (1985). 黒沢映画の美術 [The Art of Kurosawa Films] (in Japanese). Gakken. ISBN 4051016994.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Japanese)

- Official English-language website (archived)

- Official website created to commemorate Honda's 100th birthday (in Japanese)

- Ishirô Honda at IMDb

- Ishirō Honda at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- Ishirō Honda at Toho (in Japanese)

- Ishirō Honda at the National Film Archive of Japan (in Japanese)

- Ishirô Honda at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1911 births

- 1993 deaths

- 20th-century Japanese screenwriters

- People from Yamagata Prefecture

- Fantasy film directors

- Japanese horror film directors

- Science fiction film directors

- Japanese anti–nuclear weapons activists

- Japanese film editors

- Japanese male screenwriters

- Imperial Japanese Army personnel of World War II

- Imperial Japanese Army soldiers

- People with post-traumatic stress disorder

- Deaths from respiratory failure