United States and weapons of mass destruction

| United States of America | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nuclear program start date | 21 October 1939 |

| First nuclear weapon test | 16 July 1945 |

| First thermonuclear weapon test | 1 November 1952 |

| Last nuclear test | 23 September 1992 |

| Largest yield test | 15 Mt (1 March 1954) |

| Total tests | 1,054 detonations |

| Peak stockpile | 32,040 warheads (1967) |

| Current stockpile | 5,044 total[1] (2024) |

| Current strategic arsenal | 1,670[2] (2023) |

| Cumulative strategic arsenal in megatonnage | ≈820[3] (2021) |

| Maximum missile range | 13,000 km (8,078 mi) (land) 12,000 km (7,456 mi) (sub) |

| NPT party | Yes (1968, one of five recognized powers) |

The United States is known to have possessed three types of weapons of mass destruction: nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. As the country that invented nuclear weapons, the U.S. is the only country to have used nuclear weapons on another country, when it detonated two atomic bombs over two Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. It had secretly developed the earliest form of the atomic weapon during the 1940s under the title "Manhattan Project".[4] The United States pioneered the development of both the nuclear fission and hydrogen bombs (the latter involving nuclear fusion). It was the world's first and only nuclear power for four years, from 1945 until 1949, when the Soviet Union produced its own nuclear weapon. The United States has the second-largest number of nuclear weapons in the world, after the Russian Federation.[5][6]

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

Nuclear weapons

[edit]

Nuclear weapons have been used twice in combat: two nuclear weapons were used by the United States against Japan during World War II in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Altogether, the two bombings killed 105,000 people and injured thousands more[7] while devastating hundreds or thousands of military bases, factories, and cottage industries.

The U.S. conducted an extensive nuclear testing program. 1054 tests were conducted between 1945 and 1992. The exact number of nuclear devices detonated is unclear because some tests involved multiple devices while a few failed to explode or were designed not to create a nuclear explosion. The last nuclear test by the United States was on September 23, 1992; the U.S. has signed but not ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.

Currently, the United States nuclear arsenal is deployed in three areas:

- Land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs;

- Sea-based, nuclear submarine-launched ballistic missiles, or SLBMs; and

- Air-based nuclear weapons of the U.S. Air Force's heavy bomber group

The United States is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which the U.S. ratified in 1968. On October 13, 1999, the U.S. Senate rejected ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, having previously ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963. The U.S. has not, however, tested a nuclear weapon since 1992, though it has tested many non-nuclear components and has developed powerful supercomputers to duplicate the knowledge gained from testing without conducting the actual tests themselves.[8][9]

In the early 1990s, the U.S. stopped developing new nuclear weapons and now devotes most of its nuclear efforts into stockpile stewardship, maintaining and dismantling its now-aging arsenal.[10] The administration of George W. Bush decided in 2003 to engage in research towards a new generation of small nuclear weapons, especially "earth penetrators".[11] The budget passed by the United States Congress in 2004 eliminated funding for some of this research including the "bunker-busting or earth-penetrating" weapons.

The exact number of nuclear weapons possessed by the United States is difficult to determine. Different treaties and organizations have different criteria for reporting nuclear weapons, especially those held in reserve, and those being dismantled or rebuilt:

- In its Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) declaration for 2003, the U.S. listed 5968 deployed warheads as defined by START rules.[12]

- The exact number as of September 30, 2009, was 5,113 warheads, according to a U.S. fact sheet released May 3, 2010.[13]

In 2002, the United States and Russia agreed in the SORT treaty to reduce their deployed stockpiles to not more than 2,200 warheads each. In 2003, the U.S. rejected Russian proposals to further reduce both nation's nuclear stockpiles to 1,500 each.[14] In 2007, for the first time in 15 years, the United States built new warheads. These replaced some older warheads as part of the Minuteman III upgrade program.[15] 2007 also saw the first Minuteman III missiles removed from service as part of the drawdown. Overall, stockpiles and deployment systems continue to decline in number under the terms of the New START treaty.

In 2014, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists released a report, stating that there are a total of 2,530 warheads kept in reserve, and 2,120 actively deployed. Of the warheads actively deployed, the number of strategic warheads rests at 1,920 (subtracting 200 tactical B61s as part of Nato nuclear weapon sharing arrangements). The amount of warheads being actively disabled rests at about 2,700 warheads, which brings the total United States inventory to about 7,400 warheads.[16]

The U.S. government decided not to sign the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a binding agreement for negotiations for the total elimination of nuclear weapons, supported by more than 120 nations.[17]

As of early 2019, more than 90% of world's 13,865 nuclear weapons were owned by the United States and Russia. Russia has the most nuclear warheads sitting at 5,977, while the United States has 5,428 warheads.[18][19]

Land-based ICBMs

[edit]

The U.S. Air Force currently operates 400 Minuteman III ICBMs, located primarily in the northern Rocky Mountain states and the Dakotas. Peacekeeper missiles were phased out of the Air Force inventory in 2005. All USAF Minuteman II missiles were destroyed in accordance with the START treaty and their launch silos imploded and buried then sold to the public under the START II. The U.S. goal under the SORT treaty was to reduce from 1,600 warheads deployed on over 500 missiles in 2003 to 500 warheads on 450 missiles in 2012. The first Minuteman III were removed under this plan in 2007 while, at the same time, the warheads deployed on Minuteman IIIs began to be upgraded from smaller W62s to larger W87s from decommissioned Peacekeeper missiles.[15]

Air-based delivery systems

[edit]

The U.S. Air Force also operates a strategic nuclear bomber fleet. The bomber force consists of 51 nuclear-armed B-52 Stratofortresses, and 20 B-2 Spirits.[20] All 64 B-1s were retrofitted to operate in a solely conventional mode by 2007 and thus don't count as nuclear platforms.

In addition to this, the U.S. military can also deploy smaller tactical nuclear weapons either through cruise missiles or with conventional fighter-bombers. The U.S. maintains about 400 nuclear gravity bombs capable of use by the F/A-18 Hornet, F-15E, F-16, F-22 and F-35.[15] Some 350 of these bombs are deployed at seven airbases in six European NATO countries;[15] of these, 180 tactical B61 nuclear bombs fall under a nuclear sharing arrangement.[21]

Submarine-based ballistic missiles

[edit]

The U.S. Navy currently has 18 Ohio-class submarines deployed, of which 14 are ballistic missile submarines. Each submarine is equipped with a maximum complement of 24 Trident II missiles. Approximately 12 U.S. attack submarines were equipped to launch nuclear Tomahawk missiles, but these weapons were removed from service by 2013.[22]

The number of Deployed and Non-Deployed SLBMs on the Ohio-Class SSBNs as of 2018[update] is 280, of which 203 SLBMs are deployed.[20]

Biological weapons

[edit]The United States offensive biological weapons program was instigated by President Franklin Roosevelt and the U.S. Secretary of War in October 1941.[23] Research occurred at several sites. A production facility was built at Terre Haute, Indiana, but testing with a benign agent demonstrated contamination of the facility so no production occurred during World War II.[24]

The US government and military is known for using civilian populations to test the effects of bioweapons. In 1950, the US Navy conducted a secret experiment on the civilian population of the San Francisco Bay Area during operation Operation Sea-Spray, in which over 800,000 residents were unknowingly sprayed with pathogens. This led to at least one death and claims that the ecology had been changed irreversibly.[25]

In 1951, the US military also released fungal spores at the Norfolk Naval Supply Center on African-American workers to see if they are more susceptible to the pathogen than Caucasians.[26] In 1966, the US government released Bacillus globigii on the New York Subway to research how a civilian population can be used to spread pathogens. It is claimed many of those exposed were later found to exhibit long-term medical conditions of which the military has denied causation.[26]

The US government continued similar experiments on civilian populations in other cities across the country until the early 1970s.

The Dugway Proving Ground facility in Utah, opened in 1942, to this day tests and stores biological weapons. In 1968 facility infamously poisoned 6,000 sheep with the nerve agent VX. The 800,000 acre facility has reportedly weaponized fleas, mosquitoes, as well as conducted experiments on both animal and human subjects.[27]

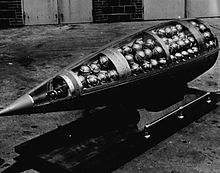

A more advanced production facility was constructed in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, which began producing biological agents in 1954. Fort Detrick, Maryland, later became a production facility as well as a research site. The U.S. developed anti-personnel and anti-crop biological weapons.[28] Several deployment systems were developed including aerial spray tanks, aerosol spray canisters, grenades, rocket warheads and cluster bombs. (See also U.S. Biological Weapon Testing)

In mid-1969, the UK and the Warsaw Pact, separately, introduced proposals to the UN to ban biological weapons, which would lead to a treaty in 1972. The U.S. cancelled its offensive biological weapons program by executive order in November 1969 (microorganisms) and February 1970 (toxins) and ordered the destruction of all offensive biological weapons, which occurred between May 1971 and February 1973. The U.S. ratified the Geneva Protocol on January 22, 1975. The U.S. ratified the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) which came into effect in March 1975.[Kissinger 1969]

Negotiations for a legally binding verification protocol to the BWC proceeded for years. In 2001, negotiations ended when the Bush administration rejected an effort by other signatories to create a protocol for verification, arguing that it could be abused to interfere with legitimate biological research.

The U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, located in Fort Detrick, produces small quantities of biological agents, for use in biological weapons defense research. According to the U.S. government, this research is performed in full accordance with the BWC.

In September 2001, shortly after the September 11 attacks on the United States, there was a series of anthrax attacks aimed at U.S. media offices and the U.S. Senate which killed five people. The anthrax used in the attacks was the Ames strain, which was first studied at Fort Detrick and then distributed to other labs around the world.

Chemical weapons

[edit]In World War I, the U.S. had its own chemical weapons program, which produced its own chemical munitions, including phosgene and mustard gas.[29] The U.S. only created about 4% of the total chemical weapons produced for that war and just over 1% of the era's most effective weapon, mustard gas. (U.S. troops suffered less than 6% of gas casualties.) Although the U.S. had begun a large-scale production of Lewisite, for use in an offensive planned for early 1919, Lewisite was not deployed during World War I.[30][31] The United States also created a special unit, the 1st Gas Regiment,[29] which used phosgene in attacks after being deployed to France.[32]

Chemical weapons were not used by the Allies or Germany during World War II for military purposes, but such weapons were deployed to Europe from the United States. In 1943, German bombers attacked the port of Bari in Southern Italy, sinking several American ships – among them John Harvey, which was carrying mustard gas. The presence of the gas was highly classified, and, according to the U.S. military account, "Sixty-nine deaths were attributed in whole or in part to the mustard gas, most of them American merchant seamen" out of 628 mustard gas military casualties.[Navy 2006][Niderost] The affair was kept secret at the time and for many years. After the war, the U.S. both participated in arms control talks involving chemical weapons and continued to stockpile them, eventually exceeding 30,000 tons of material.

After the war, all of the former Allies pursued further research on the three new nerve agents developed by the Nazis: tabun, sarin, and soman. Over the following decades, thousands of American military volunteers were exposed to chemical agents during Cold War testing programs, as well as in accidents. (In 1968, one such accident killed approximately 6,400 sheep when an agent drifted out of Dugway Proving Ground during a test.[33]) The U.S. also investigated a wide range of possible nonlethal, psychobehavioral chemical incapacitating agents including psychedelic indoles such as LSD and marijuana derivatives, as well as several glycolate anticholinergics. One of the anticholinergic compounds, 3-quinuclidinyl benzilate, was assigned the NATO code BZ and was weaponized at the beginning of the 1960s for possible battlefield use. Alleged use of chemical agents by the U.S. in the Korean (1950–53) conflict has never been substantiated.[34][35][36]

In late 1969, President Richard Nixon unilaterally renounced the first use of chemical weapons (as well as all methods of biological warfare).[37] He issued a unilateral decree halting production and transport of chemical weapons which remains in effect. From 1967 to 1970 in Operation CHASE, the U.S. disposed of chemical weapons by sinking ships laden with the weapons in the deep Atlantic. The U.S. began to research safer disposal methods for chemical weapons in the 1970s, destroying several thousand tons of mustard gas by incineration and nearly 4,200 tons of nerve agent by chemical neutralization.[38]

The U.S. entered the Geneva Protocol in 1975 (the same time it ratified the Biological Weapons Convention). This was the first operative international treaty on chemical weapons to which the U.S. was party. Stockpile reductions began in the 1980s, with the removal of some outdated munitions and destruction of the entire stock of BZ beginning in 1988. In 1990, destruction of chemical agents stored on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific began, seven years before the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) came into effect. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan began removal of the U.S. stockpile of chemical weapons from Germany[39] (see Operation Steel Box). In 1991, President George H. W. Bush unilaterally committed the U.S. to destroying all chemical weapons and renounced the right to chemical weapon retaliation.

In 1993, the U.S. signed the CWC, which required the destruction of all chemical weapon agents, dispersal systems, chemical weapons production facilities by 2012. Both Russia and U.S. missed the CWC's extended deadline of April 2012 to destroy all of their chemical weapons.[40] The United States destroyed 89.75% of the original stockpile of nearly 31,100 metric tons (30,609 long tons) of nerve and mustard agents under the terms of the treaty.[41] Chemical weapons destruction resumed in 2015.[42] The country's last stockpile was at the Blue Grass Army Depot in Kentucky.[43] The U.S. destroyed its final chemical weapon on July 7, 2023.[44] The final weapon to be destroyed was a sarin nerve agent-filled M55 rocket. The total cost for the program to destroy chemical weapons was $40 billion.[45]

See also

[edit]- Defense Threat Reduction Agency – The U.S. Department of Defense's official Combat Support Agency for countering weapons of mass destruction.

- Dugway sheep incident

- Enduring Stockpile – the name of the United States's remaining arsenal of nuclear weapons following the end of the Cold War.

- List of U.S. biological weapons topics

- Nuclear weapons and the United States

- Operation Paperclip – the codename under which the U.S. intelligence and military services extricated scientists from Germany, during and after the final stages of World War II.

- Russia and weapons of mass destruction

- Nuclear weapons of the United Kingdom

- United States Army Chemical Corps

- United States missile defense

References

[edit]- ^ "Status of World Nuclear Forces – Federation Of American Scientists". Fas.org.

- ^ "Status of World Nuclear Forces – Federation Of American Scientists". Fas.org.

- ^ M. Kristensen, Hans (2021). "United States nuclear weapons, 2021". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 77 (1). Taylor & Francis (T&F): 43–63. Bibcode:2021BuAtS..77a..43K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1859865. S2CID 231722905.

- ^ The world's nuclear stockpile. 7 April 2010.

- ^ "Status of World Nuclear Forces".

- ^ "The world's nuclear stockpile". Aljazeera. 2010-04-07.

- ^ "Total Casualties – The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". atomicarchive.com. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Scoles, Sarah. "This Bomb-Simulating US Supercomputer Broke a World Record". Wired.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons Simulations Push Supercomputing Limits". Live Science. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Gross, Daniel A. (2016). "An Aging Army". Distillations. 2 (1): 26–36. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ BBC NEWS | Americas|Mini-nukes on US agenda

- ^ "START Aggregate Numbers of Strategic Offensive Arms". www.state.gov. Archived from the original on 13 May 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Nuclear Arsenal Revealed: 5,000-Plus Warheads - AOL News". Archived from the original on 2010-05-06. Retrieved 2016-02-09."News article 3, May 2010"

- ^ Nuclear Arms Control: The U.S.-Russian Agenda

- ^ a b c d "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists" (PDF). Thebulletin.metapress.com. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ^ http://m.bos.sagepub.com/content/70/1/85.full.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "122 countries adopt 'historic' UN treaty to ban nuclear weapons". CBC News. 7 July 2017.

- ^ Reichmann, Kelsey (16 June 2019). "Here's how many nuclear warheads exist, and which countries own them". Defense News.

- ^ "Global Nuclear Arsenal Declines, But Future Cuts Uncertain Amid U.S.-Russia Tensions". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 17 June 2019.

- ^ a b United States Department of State

- ^ "Belgium, Germany Question U.S. Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe", Oliver Meier, [1] June 2005

- ^ "US Navy Instruction Confirms Retirement of Nuclear Tomahawk Cruise Missile". Federation Of American Scientists. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Committees on Biological Warfare, 1941-1948". Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ United States: Biological Weapons, [2] Federation of American Scientists, October 19, 1998

- ^ Thompson, Helen. "In 1950, the U.S. Released a Bioweapon in San Francisco". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ^ a b Bentley, Michelle. "The US has a history of testing biological weapons on the public – were infected ticks used too?". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ^ Tungul, Jade. "Inside the US government's top-secret bioweapons lab". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ^ United States Archived 2015-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Gross, Daniel A. (Spring 2015). "Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory". Distillations. 1 (1): 16–23. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ D. Hank Ellison (August 24, 2007). Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6.

- ^ Hershberg, James G. (1993). James B. Conant : Harvard to Hiroshima and the making of the nuclear age. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-8047-2619-1.

- ^ Addison, James Thayer (1919). The story of the First gas regiment. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin company. pp. 50, 146, 158, 168. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ "Is Military Research Hazardous To Veterans' Health? Lessons Spanning Half A Century". December 8, 1994. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Report for the Committee On Veterans' Affairs

- ^ 007 Incapacitating Agents

- ^ Julian Ryall (10 June 2010). "Did the US wage germ warfare in Korea?". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ "North Korea Persists in 54 year-old Disinformation". US Department of State. 9 November 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-11-12. Retrieved 2005-11-12.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Broadus, James M., et al. The Oceans and Environmental Security: Shared U.S. and Russian Perspectives, (Google Books), p. 103, Island Press, 1994, (ISBN 1559632356), accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ "The United States is still getting rid of its chemical weapons". CNN. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- ^ Army Agency Completes Mission to Destroy Chemical Weapons Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, USCMA, January 21, 2012

- ^ US to restart chemical weapon neutralisation, chemistyworld, Nina Notman, 9 February 2015

- ^ Last U.S. Chemical Weapons Stockpile Set To Be Destroyed

- ^ "U.S. destroys last of its declared chemical weapons". CBS. CBS. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Stu. "The U.S. has destroyed the last of its declared chemical weapons stockpile". NPR.

- ^ Michael Barletta and Christina Ellington (1998). "Obtain Microbial Seed Stock for Standard or Novel Agent". Iraq's Biological Weapons Program. Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies. Archived from the original on 2001-11-27. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ Center for Nonproliferation Studies (2003). "BW Agents". Iraq Profile. Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 2005-03-08. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ Henry A. Kissinger (November 1969). "Draft NSDM re United States Policy on Warfare Program and Bacteriological/Biological Research Program" (PDF). Nixon Presidential Materials, NSC Files. The National Security Archive. Retrieved 2006-09-18. Note: Declassified United States Government Document

- ^ "Naval Armed Guard Service: Tragedy at Bari, Italy on December 2, 1943". Frequently Asked Questions. United States Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Center. August 8, 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2006-09-18. Note – Original Source: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. "History of the Armed Guard Afloat, World War II." (Washington, 1946): 166-169.

- ^ Niderost, Eric. "German Raid on Bari". World War II. Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2006-09-18. Note – Original URL Archived 2006-05-29 at the Wayback Machine redirected to the URL shown here; article lacks date or volume reference.

External links

[edit]- New START Treaty Aggregate Numbers of Strategic Offensive Arms

- Video archive of the US's Nuclear Testing

- United States Nuclear Forces Guide

- Abolishing Weapons of Mass Destruction: Addressing Cold War and Other Wartime Legacies in the Twenty-First Century By Mikhail S. Gorbachev

- Nuclear Threat Initiative on United States

- U.S. Army Chemical Weapons Agency website

- Nuclear Notebook: U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2006[permanent dead link] by Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January/February 2006.

- Lessons Lost[permanent dead link], by Joseph Cirincione. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2005.

- Nuclear Files.org Current information on nuclear stockpiles in the United States

- Trends in U.S. Nuclear Policy - analysis by William C. Potter, IFRI Proliferation Papers n°11, 2005

- The Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project or NPIHP is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews and other empirical sources.