Eurovision Song Contest 1989

| Eurovision Song Contest 1989 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dates | |

| Final | 6 May 1989 |

| Host | |

| Venue | Palais de Beaulieu Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Presenter(s) | |

| Musical director | Benoît Kaufman |

| Directed by | Alain Bloch Charles-André Grivet |

| Executive supervisor | Frank Naef |

| Executive producer | Raymond Zumsteg |

| Host broadcaster | Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG SSR) Télévision suisse romande (TSR) |

| Website | eurovision |

| Participants | |

| Number of entries | 22 |

| Debuting countries | None |

| Returning countries | |

| Non-returning countries | None |

| |

| Vote | |

| Voting system | Each country awarded 12, 10, 8–1 point(s) to their 10 favourite songs |

| Winning song | "Rock Me" |

The Eurovision Song Contest 1989 was the 34th edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, held on 6 May 1989 in the Palais de Beaulieu in Lausanne, Switzerland. Organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and host broadcaster Télévision suisse romande (TSR) on behalf of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG SSR), and presented by Jacques Deschenaux and Lolita Morena, the contest was held in Switzerland following the country's victory at the 1988 contest with the song "Ne partez pas sans moi" by Céline Dion.

Twenty-two countries participated in the contest, with Cyprus returning after a one-year absence. Among the participating artists were the two youngest artists to have ever participated in the contest, 12-year-old Gili Netanel and 11-year-old Nathalie Pâque representing Israel and France, respectively; the inclusion of the young performers led to some controversy in the run-up to the event, including calls for their exclusion from the contest, and although no action was taken by the organisers of this event it did result in a rule change for the following year's contest.

The winner was Yugoslavia with the song "Rock Me", composed by Rajko Dujmić, written by Stevo Cvikić and performed by the group Riva. This was Yugoslavia's first contest victory in twenty-four attempts. The United Kingdom, Denmark, Sweden and Austria rounded out the top five positions; the UK and Denmark placed second and third respectively for a second consecutive year, and Austria finished in the top five for the first time since 1976. Finland gained their best result since 1975, while Ireland and Iceland achieved their worst ever placings to date, placing eighteenth and twenty-second respectively, with Iceland ultimately earning nul points and coming last for the first time.

Location

[edit]

The 1989 contest took place in Lausanne, Switzerland, following the country's victory at the 1988 contest with the song "Ne partez pas sans moi" performed by Céline Dion. It was the second time that Switzerland had hosted the event, following the inaugural edition of the contest held in 1956 in Lugano.[1]

The chosen venue was the Palais de Beaulieu, a convention and exhibition centre. The contest took place in the Hall 7 of the Palais, also known as the Halle des Fêtes, which was temporarily renamed Salle Lys Assia in honour of Switzerland's first Eurovision winning artist.[2][3] An audience of around 1,600 people could occupy the Salle Lys Assia during the contest.[4] Over a dozen cities were reported to have applied to host the contest, with Lausanne winning out due to its combination of a suitable production venue, logistical infrastructure availability, and proximity to an international airport.[5][6]

Participating countries

[edit]| Eurovision Song Contest 1989 – Participation summaries by country | |

|---|---|

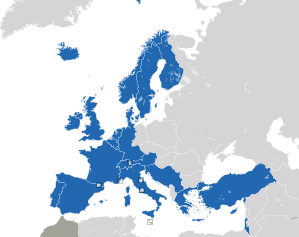

Twenty-two countries participated in the 1989 contest, with the twenty-one countries from the previous year's event being joined by Cyprus, returning after a one-year absence.[2][7]

For the first time, Switzerland sent an entry in Romansh, the smallest of Switzerland's four national languages.[2][7]

No artists competing in the 1989 contest had previously taken part as lead artists in previous events, however, two of the artists had previously performed in the contest in past editions. The Netherlands's Justine Pelmelay had been one of the backing vocalists supporting the Dutch entrant Gerard Joling in the 1988 event, and Greece's Marianna had also performed as a backing vocalist in 1987 for Bang.[8][9] Additionally, Søren Bundgaard who had represented Denmark in three previous editions of the contest as a member of the duo Hot Eyes, was one of Birthe Kjær's backing performers in this year's event.[10][11]

For the first time since 1980, the event featured two participating songs written by the same songwriters: both the German and Austrian entries were written by Dieter Bohlen and Joachim Horn-Bernges.[12]

The 1989 contest featured the youngest ever lead performers, in the form of 12-year-old Gili Netanel and 11-year-old Nathalie Pâque representing Israel and France respectively. Their inclusion in the contest led to controversy and protest from some of the other competitors, who felt their young age should preclude them from the contest. As there were no existing rules regarding the age of performers, the two artists were allowed to compete, however, the controversy led to the introduction of an age restriction on performing artists for the 1990 contest.[2][7][12]

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) | Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Thomas Forstner | "Nur ein Lied" | German | No conductor | ||

| BRT | Ingeborg | "Door de wind" | Dutch | Stef Bos | Freddy Sunder | |

| CyBC | Fanny Polymeri and Yiannis Savvidakis | "Apopse as vrethoume" (Απόψε ας βρεθούμε) | Greek |

|

Haris Andreadis | |

| DR | Birthe Kjær | "Vi maler byen rød" | Danish | Henrik Krogsgaard[a] | ||

| YLE | Anneli Saaristo | "La dolce vita" | Finnish |

|

Ossi Runne | |

| Antenne 2 | Nathalie Pâque | "J'ai volé la vie" | French |

|

Guy Mattéoni | |

| BR[b] | Nino de Angelo | "Flieger" | German |

|

No conductor | |

| ERT | Marianna | "To diko sou asteri" (Το δικό σου αστέρι) | Greek |

|

Giorgos Niarchos | |

| RÚV | Daníel | "Það sem enginn sér" | Icelandic | Valgeir Guðjónsson | No conductor | |

| RTÉ | Kiev Connolly and the Missing Passengers | "The Real Me" | English | Kiev Connolly | Noel Kelehan | |

| IBA | Gili and Galit | "Derekh Hamelekh" (דרך המלך) | Hebrew | Shaike Paikov | Shaike Paikov | |

| RAI | Anna Oxa and Fausto Leali | "Avrei voluto" | Italian |

|

Mario Natale | |

| CLT | Park Café | "Monsieur" | French |

|

Benoît Kaufman | |

| NOS | Justine Pelmelay | "Blijf zoals je bent" | Dutch | Harry van Hoof | ||

| NRK | Britt Synnøve Johansen | "Venners nærhet" | Norwegian |

|

Pete Knutsen | |

| RTP | Da Vinci | "Conquistador" | Portuguese |

|

Luís Duarte | |

| TVE | Nina | "Nacida para amar" | Spanish | Juan Carlos Calderón | Juan Carlos Calderón | |

| SVT | Tommy Nilsson | "En dag" | Swedish | Anders Berglund | ||

| SRG SSR | Furbaz | "Viver senza tei" | Romansh | Marie Louise Werth | Benoît Kaufman | |

| TRT | Pan | "Bana Bana" | Turkish | Timur Selçuk | Timur Selçuk | |

| BBC | Live Report | "Why Do I Always Get It Wrong" | English |

|

Ronnie Hazlehurst | |

| JRT | Riva | "Rock Me" | Serbo-Croatian |

|

Nikica Kalogjera |

Production

[edit]

The Eurovision Song Contest 1989 was produced by the Swiss public broadcaster Télévision suisse romande (TSR) on behalf of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (German: Schweizerische Radio- und Fernsehgesellschaft; French: Société suisse de radiodiffusion et télévision; SRG SSR).[17][18] Raymond Zumsteg served as executive producer, Alain Bloch served as producer and director, Charles-André Grivet served as director, Paul Waelti served as designer, and Benoît Kaufman served as musical director leading an assembled orchestra of 55 musicians.[7][19][20][21] A separate musical director could be nominated by each country to lead the orchestra during their performance, with the host musical director also available to conduct for those countries which did not nominate their own conductor.[13]

Following the confirmation of the twenty-two competing countries, the draw to determine the running order of the contest was held on 23 November 1988.[2] Production details related to the contest were also shared on this date, including the contest's mascot and logo. The mascot, Cindy Aeschbach, an 11-year old girl from Morges, was chosen from among two hundred girls from schools in the Swiss region of La Côte to embody the character of Heidi in the contest's opening sequence.[21][22][23] The logo, designed by Fritz Aeschbach, is a representation of the Matterhorn created with computer graphics, constructed using contour lines to represent the strings of a guitar, and featuring a silhouette outline of Lausanne Cathedral at the base.[23] The presenters of the contest were publicly revealed on 17 January 1989: the sports journalist and television presenter Jacques Deschenaux and the television presenter and Miss Switzerland 1982 Lolita Morena were chosen from among several candidates considered by TSR.[4][13][24]

Rehearsals for the participating artists began on 1 May 1989. Two technical rehearsals were conducted for each participating delegation in the week approaching the contest, with countries rehearsing in the order in which they would perform. The first rehearsals of 50 minutes were held on 1 and 2 May, followed by a press conference for each delegation and the accredited press.Each country's second rehearsals were held on 3 and 4 May and lasted 35 minutes total. Three dress rehearsals were held with all artists, held in the afternoon and evening of 5 May and in the afternoon of 6 May; all dress rehearsals were held in front of an audience, although for the afternoon rehearsal on 5 May, the acts were not required to be in their performance costumes.[2]

During the contest week each delegation also took part in recording sessions for the postcards, short films which served as an introduction to each country's entry, as well as providing an opportunity for transition between entries and allow stage crew to make changes on stage. Footage for the postcards were filmed between 1 and 4 May for the delegations, with the exception of the Swiss delegation which filmed for their postcard in the weeks leading up to the contest; delegations recorded for their postcards on one of the days in which they were not required to be present at the contest venue.[2][25][26] Delegations were also invited to a number of special events during the contest week: on 1 May a welcome reception was hosted by the Council of States of the canton of Vaud and the municipality of Lausanne in the ballroom of the Palais de Beaulieu; on 2 May, Céline Dion performed her first show on Swiss soil as part of her Incognito Tour at the Théâtre de Beaulieu; a dinner cruise on Lake Geneva was organised for 3 May; and a reception on 5 May was organsised by the tourist office of the canton of Grisons.[2][27][28]

Format

[edit]Each participating broadcaster submitted one song, which was required to be no longer than three minutes in duration and performed in the language, or one of the languages, of the country which it represented.[29][30] A maximum of six performers were allowed on stage during each country's performance.[29][31] Each entry could utilise all or part of the live orchestra and could use instrumental-only backing tracks, however any backing tracks used could only include the sound of instruments featured on stage being mimed by the performers.[31][32]

The results of the 1989 contest were determined through the same scoring system as had first been introduced in 1975: each country awarded twelve points to its favourite entry, followed by ten points to its second favourite, and then awarded points in decreasing value from eight to one for the remaining songs which featured in the country's top ten, with countries unable to vote for their own entry.[33] The points awarded by each country were determined by an assembled jury of sixteen individuals, who were all required to be members of the public with no connection to the music industry, split evenly between men and women and by age. Each jury member voted in secret and awarded between one and ten votes to each participating song, excluding that from their own country and with no abstentions permitted. The votes of each member were collected following the country's performance and then tallied by the non-voting jury chairperson to determine the points to be awarded. In any cases where two or more songs in the top ten received the same number of votes, a show of hands by all jury members was used to determine the final placing.[34][35]

Partly due to the close result at the previous year's event, the tie-break procedure, to determine a single winner should two or more countries finish in first place with the same number of points, was modified. For the 1989 event and for future contents, an analysis of the tied countries' top marks would be conducted, with the country that received the most 12-point scores being declared the winner. If a tie for first place remained then the country with the most 10 points would be crowned the winner. Should two or more countries still remain tied for first place after analysing both 12- and 10-point scores then the tying countries would be declared joint winners.[2][7]

Contest overview

[edit]

The contest took place on 6 May 1989 at 21:00 (CEST) with a duration of 3 hours and 10 minutes and was presented by Jacques Deschenaux and Lolita Morena.[7][13]

The contest opened with a seven minute film, directed by Jean-Marc Panchaud, highlighting modern Swiss landscapes and themes in juxtaposition with paintings by celebrated Swiss artists and starring Sylvie Aeschbach as Heidi.[3][21][23] This was followed by performances in the contest venue by the reigning Eurovision winner Célion Dion, who performed both her winning song from the 1988 contest "Ne partez pas sans moi" and the premiere of her first English language single "Where Does My Heart Beat Now".[36][37] The interval act was the stunt artist Guy Tell; modelling himself after the Swiss folk hero William Tell, Guy Tell used high-powered crossbows to pierce various targets with precision at distance. The climax of the performance featured sixteen crossbows being positioned to set off a chain reaction in sequence, with the arrow from the first crossbow hitting a target which set off the next crossbow, culminating in an arrow piercing an apple set above the head of the performer. Ultimately however, on the night of the contest itself, the final arrow missed the apple slightly by a few centimetres.[12][38][39] The trophy awarded to the winners was presented at the end of the broadcast by Céline Dion and Sylvie Aeschbach.[40]

The winner was Yugoslavia represented by the song "Rock Me", composed by Rajko Dujmić, written by Stevo Cvikić and performed by the band Riva.[41] It was Yugoslavia's first Eurovision win on their twenty-fourth contest appearance, becoming the seventeenth nation to win the contest.[12][42] It would also prove to be the country's only win, as the nation would begin to break into separate states two years later and would eventually participate for the last time in 1992.[43] It was the sixth time that the song which was performed last ended up winning the contest.[34] The United Kingdom and Denmark placed second and third respectively for the second consecutive year, with the UK finishing in second place for the twelfth time in total.[12][34] Austria finished in the top five for the first time since 1976, while Finland achieved its best result since 1975.[44][45] Ireland achieved their worst result to date, and for the third consecutive year one of the participating countries failed to receive any points, on this occasion Iceland became the newest country to receive nul points, their worst result in four years of participation.[12][46][47] During the traditional winner's reprise performance, Riva sung the winning song entirely in English.[34]

| R/O | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anna Oxa and Fausto Leali | "Avrei voluto" | 56 | 9 | |

| 2 | Gili and Galit | "Derekh Hamelekh" | 50 | 12 | |

| 3 | Kiev Connolly and the Missing Passengers | "The Real Me" | 21 | 18 | |

| 4 | Justine Pelmelay | "Blijf zoals je bent" | 45 | 15 | |

| 5 | Pan | "Bana Bana" | 5 | 21 | |

| 6 | Ingeborg | "Door de wind" | 13 | 19 | |

| 7 | Live Report | "Why Do I Always Get It Wrong" | 130 | 2 | |

| 8 | Britt Synnøve Johansen | "Venners nærhet" | 30 | 17 | |

| 9 | Da Vinci | "Conquistador" | 39 | 16 | |

| 10 | Tommy Nilsson | "En dag" | 110 | 4 | |

| 11 | Park Café | "Monsieur" | 8 | 20 | |

| 12 | Birthe Kjær | "Vi maler byen rød" | 111 | 3 | |

| 13 | Thomas Forstner | "Nur ein Lied" | 97 | 5 | |

| 14 | Anneli Saaristo | "La dolce vita" | 76 | 7 | |

| 15 | Nathalie Pâque | "J'ai volé la vie" | 60 | 8 | |

| 16 | Nina | "Nacida para amar" | 88 | 6 | |

| 17 | Fanny Polymeri and Yiannis Savvidakis | "Apopse as vrethoume" | 51 | 11 | |

| 18 | Furbaz | "Viver senza tei" | 47 | 13 | |

| 19 | Marianna | "To diko sou asteri" | 56 | 9 | |

| 20 | Daníel | "Það sem enginn sér" | 0 | 22 | |

| 21 | Nino de Angelo | "Flieger" | 46 | 14 | |

| 22 | Riva | "Rock Me" | 137 | 1 |

Spokespersons

[edit]Each country nominated a spokesperson, connected to the contest venue via telephone lines and responsible for announcing, in English or French, the votes for their respective country.[29][49] Known spokespersons at the 1989 contest are listed below.

Iceland – Erla Björk Skúladóttir[50]

Iceland – Erla Björk Skúladóttir[50] Ireland – Eileen Dunne[51]

Ireland – Eileen Dunne[51] Sweden – Agneta Bolme Börjefors[52]

Sweden – Agneta Bolme Börjefors[52] United Kingdom – Colin Berry[34]

United Kingdom – Colin Berry[34]

Detailed voting results

[edit]Jury voting was used to determine the points awarded by all countries.[34] The announcement of the results from each country was conducted in the order in which they performed, with the spokespersons announcing their country's points in English or French in ascending order.[20][34] The detailed breakdown of the points awarded by each country is listed in the tables below.

Total score

|

Italy

|

Israel

|

Ireland

|

Netherlands

|

Turkey

|

Belgium

|

United Kingdom

|

Norway

|

Portugal

|

Sweden

|

Luxembourg

|

Denmark

|

Austria

|

Finland

|

France

|

Spain

|

Cyprus

|

Switzerland

|

Greece

|

Iceland

|

Germany

|

Yugoslavia

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contestants

|

Italy | 56 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||||||||

| Israel | 50 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Ireland | 21 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 45 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Turkey | 5 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 13 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 130 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 6 | |||||

| Norway | 30 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 39 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 110 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 12 | |||||||

| Luxembourg | 8 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 111 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 1 | |||||||

| Austria | 97 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| Finland | 76 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 10 | |||||||||||

| France | 60 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| Spain | 88 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||

| Cyprus | 51 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 12 | |||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 47 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||

| Greece | 56 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Iceland | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 46 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Yugoslavia | 137 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | |||||

12 points

[edit]The below table summarises how the maximum 12 points were awarded from one country to another. The winning country is shown in bold. The United Kingdom received the maximum score of 12 points from five of the voting countries, with Yugoslavia receiving four sets of 12 points, Austria, Denmark and Sweden each receiving three sets of maximum scores, Greece receiving two sets of 12 points, and Cyprus and Italy receiving one maximum score each.[53][54]

| N. | Contestant | Nation(s) giving 12 points |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 1 | ||

Broadcasts

[edit]Each participating broadcaster was required to relay the contest via its networks. Non-participating member broadcasters were also able to relay the contest as "passive participants". Broadcasters were able to send commentators to provide coverage of the contest in their own native language and to relay information about the artists and songs to their television viewers.[31] It was reportedly broadcast on 33 channels from 30 countries and over half a billion viewers and listeners have watched the contest.[55]

Known details on the broadcasts in each country, including the specific broadcasting stations and commentators are shown in the tables below.

| Country | Broadcaster | Channel(s) | Commentator(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | SBS TV[e] | [91] | ||

| TV5 | TV5 Québec Canada[f] | [92] | ||

| ČST | ČST1[g] | [93] | ||

| ETV | [94] | |||

| SvF | [95] | |||

| KNR | KNR[h] | [96] | ||

| MTV | MTV2[i] | [88] | ||

| TP | TP1[j] | [97] | ||

| CT USSR | Programme One | [98] | ||

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Entry partly conducted by Benoît Kaufman, as partway through the performance Krogsgaard joined Kjær on stage as a backing singer.[13]

- ^ On behalf of the German public broadcasting consortium ARD[16]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 23:10 (CEST)[72]

- ^ Broadcast through a second audio programme on TSR[79]

- ^ Deferred broadcast on 7 May at 20:30 (AEST)[91]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 20:00 (EDT)[92]

- ^ Delayed broadcast on 13 May 1989 at 21:20 (CEST)[93]

- ^ Delayed broadcast on 20 May 1989 at 21:30 (WGST)[96]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 22:00 (CEST)[88]

- ^ Delayed broadcast on 20 May 1989 at 20:05 (CEST)[97]

References

[edit]- ^ "Switzerland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roxburgh 2016, pp. 371–373.

- ^ a b "Finale 1989 du concours Eurovision de la chanson à Lausanne: Une opération délicate" [1989 Eurovision Song Contest final in Lausanne: A delicate operation]. Nouvelliste et Feuille d'Avis du Valais (in French). Sion, Switzerland. 24 November 1988. Retrieved 9 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Le couple Eurovision" [The Eurovision couple]. Journal de Jura (in French). Bienne, Switzerland. 18 January 1989. p. 1. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Concours Eurovision am 6. Mai 1989 in Lausanne" [Eurovision Song Contest on 6th May 1989 in Lausanne]. Walliser Bote (in German). Brig/Visp, Switzerland. 2 July 1988. p. 5. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "SRG wählte Lausanne" [SRG chose Lausanne]. Bieler Tagblatt (in German). Biel, Switzerland. 2 July 1988. p. 5. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b c d e f "Lausanne 1989 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Indonesia's Eurovision connections". Aussievision. 16 August 2023. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Trimi, Epi (4 August 2021). "Μαριάννα Ευστρατίου: Η Μις Γιουροβίζιον που πλήρωσε η ίδια τη συμμετοχή της και οι μεγάλες συνεργασίες" [Marianna Efstratiou: The Miss Eurovision who paid for her participation herself and the great collaborations]. Enimerotiko (in Greek). Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Eurovision legends to perform at Danish final". European Broadcasting Union. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Bygbjerg, Søren (20 January 2009). "Hele Danmarks Birthe Kjær" [The whole of Denmark's Birthe Kjær] (in Danish). DR. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Connor 2010, pp. 116–119.

- ^ a b c d e Roxburgh 2016, pp. 374–381.

- ^ "Participants of Lausanne 1989". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "1989 – 34th edition". diggiloo.net. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel" [All German ESC acts and their songs]. www.eurovision.de (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "Le Concours Eurovision de la chanson à Lausanne" [The Eurovision Song Contest in Lausanne]. Radio Télévision Suisse. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Eurovision: cuvée 89" [Eurovision: vintage 89]. Radio TV8 (in French). Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland: Ringier. 24 November 1988. p. 23. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ Roxburgh 2016, p. 374.

- ^ a b Concours Eurovision de la Chanson: Lausanne 1989 [Eurovision Song Contest: Lausanne 1989] (Television programme) (in English, French, and German). Lausanne, Switzerland: Société suisse de radiodiffusion et télévision. 6 May 1989.

- ^ a b c "Lausanne prépare le 34e Concours «Eurovision» de la chanson en 1989" [Lausanne organises the 34th Eurovision Song Contest in 1989]. Journal et Feuille d'Avis de Vevey-Riviera (in French). Vevey, Switzerland: Saüberlin & Pfeiffer SA. 24 November 1988. p. 6. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ "Eine Nacht lang Schlager-Metropole" [A schlager metropolis for one night]. Freiburger Nachrichten (in German). Fribourg, Switzerland. 24 November 1988. p. 44. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b c Krol, Pierre-André (5 May 1989). "Cindy, notre princesse de l'Eurovision" [Cindy, our Eurovision princess]. L'Illustré (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland: Ringier. pp. 22–26. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ "Concours Eurovision de la Chanson: Jacques et Lolita comme présentateurs" [Eurovision Song Contest: Jacques and Lolita as preseters]. Nouvelle revue de Lausanne (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland. 18 January 1989. p. 17. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ Egan, John (22 May 2015). "All Kinds of Everything: a history of Eurovision Postcards". ESC Insight. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Kurris, Denis (1 May 2022). "Eurovision 2022: The theme of this year's Eurovision postcards". ESC Plus. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "La fièvre de samedi" [Saturday fever]. L'Express (in French). Neuchâtel, Switzerland. 2 May 1989. p. 40. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Concert Céline Dion "Grand Prix Eurovision"". Journal de Genève (in French). 12 April 1989. p. 20. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ a b c "How it works – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 18 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Jerusalem 1999 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

For the first time since the 1970s participants were free to choose which language they performed in.

- ^ a b c "The Rules of the Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (18 April 2020). "#EurovisionAgain travels back to Dublin 1997". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

The orchestra also saw their days numbered as, from 1997, full backing tracks were allowed without restriction, meaning that the songs could be accompanied by pre-recorded music instead of the live orchestra.

- ^ "In a Nutshell – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Roxburgh 2016, pp. 381–383.

- ^ Roxburgh 2016, p. 347.

- ^ Kahn, Olivier (29 April 1989). "Céline Dion après et avant l'Eurovision: 'Pour gagner, il faut rester soi-même" [Céline Dion after and before Eurovision: 'To win you have to stay yourself']. 24 heures (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland: Edipresse. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ A.B. (3 May 1989). "Le rêve américain" [The American dream]. Le Matin (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland: 24 Heures Presse SA. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ Zufferey, Jean-Charles (8 May 1989). "Grand Prix Eurovision de la Chanson à Lausanne" [Eurovision Song Contest in Lausanne]. Nouvelle revue de Lausanne (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ Roxburgh 2016, pp. 361.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 216.

- ^ "Riva – Yugoslavia – Lausanne 1989". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Yugoslavia – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (17 September 2017). "Rock me baby! Looking back at Yugoslavia at Eurovision". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Austria – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Finland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Iceland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Butler, Sinead (14 May 2022). "Eurovision: All the nil point performances from the Eurovision Song Contest | indy100". Indy100. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Final of Lausanne 1989". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Lugano to Liverpool: Broadcasting Eurovision". National Science and Media Museum. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Söngvakeppnin: Fjórir valdir til að syngja bakraddir" [Eurovision: Four chosen to sing backing vocals]. Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic). Reykjavík, Iceland. 12 April 1989. p. 19. Retrieved 28 May 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ O'Loughlin, Mikie (8 June 2021). "RTE Eileen Dunne's marriage to soap star Macdara O'Fatharta, their wedding day and grown up son Cormac". RSVP Live. Reach plc. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Thorsson & Verhage 2006, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c "Results of the Final of Lausanne 1989". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Eurovision Song Contest 1989 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Ćirić, E. (8 May 1989). "Pravi šlager za Evropu" [A real hit for Europe]. Borba (in Serbian). Belgrade, SR Serbia, Yugoslavia. p. 20. Retrieved 30 June 2024 – via Pretraživa digitalna biblioteka.

- ^ "TV Avstrija 1 – So 6.5" [TV Austria 1 – Sat 06/05]. Slovenski vestnik (in Slovenian). Klagenfurt (Celovec), Austria. 3 May 1989. p. 7. Retrieved 11 June 2024 – via Digital Library of Slovenia.

- ^ a b "Radio/Televisie" [Radio/Television]. Leidse Courant (in Dutch). Leiden, Netherlands. 6 May 1989. p. 20. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Samstag, 6 Mai | Samedi, 6 mai" [Saturday 6 May]. Agenda (in French, German, and Luxembourgish). No. 18. 6–12 May 1989. pp. 10–13. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Τηλεόραση – Το πλήρες πρόγραμμα" [Television – The full programme]. O Phileleftheros (in Greek). Nicosia, Cyprus. 6 May 1989. p. 2. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024 – via Press and Information Office.

- ^ "Ραδιοφωνο" [Radio]. I Simerini (in Greek). Nicosia, Cyprus. 6 May 1989. p. 6. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024 – via Press and Information Office.

- ^ "Alle tiders programoversigter – Lørdag den 6. maj 1989" [All-time programme overviews – Saturday 6th May 1989]. DR. Archived from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Radio · Televisio" [Radio · Television]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. 6 May 1989. pp. 68–69. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Marion Rung laulut ja Dolce Vita" [Marion Rung's songs and Dolce Vita]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 6 May 1989. p. 69. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Radio-télévision – Samedi 6 mai" [Radio-television – Saturday 6 May]. Le Monde. Paris, France. 6 May 1989. p. 19. Retrieved 18 June 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c "Samedi 6 mai" [Saturday 6 May]. Radio TV8 (in French). No. 17. Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland: Ringier. 27 April 1989. pp. 60–65. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ "Televisie en radio" [Television and radio]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). Heerlen, Netherlands. 6 May 1989. p. 8. Retrieved 26 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Το πρόγραμμα της τηλεόρασης" [TV schedule]. Imerisia (in Greek). Veria, Greece. 6 May 1989. p. 4. Retrieved 23 June 2024 – via Public Central Library of Veria.

- ^ "Laugurdagur 6. maí" [Saturday 6 May]. DV (in Icelandic). Reykjavík, Iceland. 6 May 1989. p. 3. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Saturday's Television". The Irish Times Weekend. 6 May 1989. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Radio". The Irish Times Weekend. 6 May 1989. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "יום שבת 6.5.89 – טלוויזיה" [Saturday 06/05/89 – Television]. Maariv (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv, Israel. 5 May 1989. pp. 146–147. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023 – via National Library of Israel.

- ^ a b "Sabato 6 maggio" [Saturday 6 May]. Radiocorriere TV (in Italian). Vol. 66, no. 18. 30 April – 6 May 1989. pp. 122–125, 127–129. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "Radio/TV". Ringerikes Blad (in Norwegian). Hønefoss, Norway. 6 May 1989. p. 12. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via National Library of Norway.

- ^ "P2 – Kjøreplan lørdag 6. mai 1989" [P2 – Schedule Saturday 6 May 1989] (in Norwegian). NRK. 6 May 1989. p. 4. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via National Library of Norway. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- ^ "Televisão" [Television]. Diário de Lisboa (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal. 6 May 1989. p. 23. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022 – via Casa Comum.

- ^ "El Festival de Eurovisión, en directo por la Segunda Cadena" [The Eurovision Song Contest, live on the Second Channel]. La Tribuna de Albacete (in Spanish). Albacete, Spain. 6 May 1989. p. 35. Retrieved 28 June 2024 – via Biblioteca Virtual de Prensa Histórica.

- ^ "TV-programmen" [TV programmes]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. 6 May 1989. p. 17.

- ^ "Radioprogrammen" [Radio programmes]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. 6 May 1989. p. 17.

- ^ a b "Fernsehen" [Television]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Zürich, Switzerland. 6 May 1989. p. 31. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Mass Smedia". Eco di Locarno (in Italian). Locarno, Switzerland. 6 May 1989. p. 7. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022 – via Sistema bibliotecario ticinese.

- ^ "Radio–TV Samedi" [Radio–TV Saturday]. Le Temps (in French). Geneva, Switzerland. 6 May 1989. p. 34. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Radio". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Zürich, Switzerland. 6 May 1989. p. 30. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "1. Gün / Cumartesi" [Day 1 / Saturday]. Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey. 6 May 1989. p. 7. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision'a tepki" [Reaction to Eurovision]. Milliyet (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey. 9 May 1989. p. 9. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC One". Radio Times. 6 May 1989. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "The Eurovision Song Contest – BBC Radio 2". Radio Times. 6 May 1989. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "Телевизија – Субота, 6. мај 1989" [Television – Saturday, 6 May 1989]. Borba (in Serbian). Belgrade, SR Serbia, Yugoslavia. 6–7 May 1989. p. 20. Retrieved 27 May 2024 – via Pretraživa digitalna biblioteka.

- ^ a b c "Televizió" [Television]. Magyar Szó (in Hungarian). Novi Sad, SAP Vojvodina, Yugoslavia. 6 May 1989. p. 24. Retrieved 18 June 2024 – via Vajdasági Magyar Digitális Adattár.

- ^ "rtv" [Radio TV]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Split, SR Croatia, Yugoslavia. 6 May 1989. p. 31. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Spored za soboto – Television" [Schedule for Saturday – Television]. Delo (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, SR Slovenia, Yugoslavia. 6 May 1989. p. 14. Retrieved 28 October 2024 – via Digital Library of Slovenia.

- ^ a b "TV Guide – Sunday May 7". The Canberra Times. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 1 May 1989. p. 12. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "La télévision de samedi soir en un clin d'oeil" [Saturday night television at a glance]. Le Devoir. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 6 May 1989. p. C-10. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "sobota 13. 5. /1/" [Saturday 13/05 /1/]. Rozhlasový týdeník (in Czech). No. 20. 29 April 1989. p. 15. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 19 May 2024 – via Kramerius.

- ^ "L. 6. V" [S. 6 May]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 18. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 1–7 May 1989. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

- ^ "Sjónvarp – Sjónvarpsskráin – 6. mai - 11. mai" [Television – TV schedule – 6 May - 11 May]. Oyggjatíðindi (in Faroese and Danish). Hoyvík, Faroe Islands. 6 May 1989. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 16 July 2024 – via Infomedia.

- ^ a b "TV-KNR – 20. maj Lørdag" [TV-KNR – 20 May Saturday]. Atuagagdliutit (in Kalaallisut and Danish). Nuuk, Greenland. 19 May 1989. p. 7. Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ a b "Program telewizji – sobota – 20 V" [Television Programme – Saturday – 20 May]. Dziennik Polski (in Polish). Kraków, Poland. 19 May 1989. p. 8. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2023 – via Digital Library of Małopolska.

- ^ "Телевидение, программа на неделю" [Television, weekly program] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 6 May 1989. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2016). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Three: The 1980s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Thorsson, Leif; Verhage, Martin (2006). Melodifestivalen genom tiderna : de svenska uttagningarna och internationella finalerna [Melodifestivalen through the ages: the Swedish selections and international finals] (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Premium Publishing. ISBN 91-89136-29-2.