Taft–Hartley Act

| |

| Long title | An Act to amend the National Labor Relations Act, to provide additional facilities for the mediation of labor disputes affecting commerce, to equalize legal responsibilities of labor organizations and employers, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Taft–Hartley Act |

| Enacted by | the 80th United States Congress |

| Effective | June 23, 1947 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 80–101 |

| Statutes at Large | 61 Stat. 136 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 29 U.S.C.: Labor |

| U.S.C. sections created | 29 U.S.C. ch. 7 §§ 141-197 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| |

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United States Congress over the veto of President Harry S. Truman, becoming law on June 23, 1947.

Taft–Hartley was introduced in the aftermath of a major strike wave in 1945 and 1946. Though it was enacted by the Republican-controlled 80th Congress, the law received significant support from congressional Democrats, many of whom joined with their Republican colleagues in voting to override Truman's veto. The act continued to generate opposition after Truman left office, but it remains in effect.

The Taft–Hartley Act amended the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), adding new restrictions on union actions and designating new union-specific unfair labor practices. Among the practices prohibited by the Taft–Hartley act are jurisdictional strikes, wildcat strikes, solidarity or political strikes, secondary boycotts, secondary and mass picketing, closed shops, and monetary donations by unions to federal political campaigns. The amendments also allowed states to enact right-to-work laws banning union shops. Enacted during the early stages of the Cold War, the law required union officers to sign non-communist affidavits with the government.

Background

[edit]In 1945 and 1946, an unprecedented wave of major strikes affected the United States; by February 1946, nearly 2 million workers were engaged in strikes or other labor disputes. Organized labor had largely refrained from striking during World War II, but with the end of the war, labor leaders were eager to share in the gains from a postwar economic resurgence.[1]

The 1946 mid-term elections left Republicans in control of Congress for the first time since the early 1930s.[2] Many of the newly elected congressmen were strongly conservative and sought to overturn or roll back New Deal legislation such as the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which had established the right of workers to join unions, bargain collectively, and engage in strikes.[3] Republican senator Robert A. Taft and Republican congressman Fred A. Hartley Jr. each introduced measures to curtail the power of unions and prevent strikes. Taft's bill passed the Senate by a 68-to-24 majority, but some of its original provisions were removed by moderates, like Republican senator Wayne Morse. Meanwhile, the stronger Hartley bill garnered a 308-to-107 majority in the House of Representatives. The Taft–Hartley bill that emerged from a conference committee incorporated aspects from both the House and Senate bills.[4] The bill was promoted by large business lobbies, including the National Association of Manufacturers.[5]

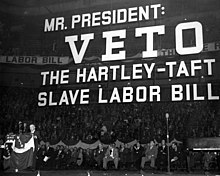

After spending several days considering how to respond to the bill, President Truman vetoed Taft–Hartley with a strong message to Congress,[6] calling the act a "dangerous intrusion on free speech."[7] Labor leaders, meanwhile, derided the act as a "slave-labor bill".[8] Despite Truman's all-out effort to prevent a veto override, Congress overrode his veto with considerable Democratic support, including 106 out of 177 Democrats in the House, and 20 out of 42 Democrats in the Senate.[9][10]

Effects of the act

[edit]As stated in Section 1 (29 U.S.C. § 141), the purpose of the NLRA is:

[T]o promote the full flow of commerce, to prescribe the legitimate rights of both employees and employers in their relations affecting commerce, to provide orderly and peaceful procedures for preventing the interference by either with the legitimate rights of the other, to protect the rights of individual employees in their relations with labor organizations whose activities affect commerce, to define and proscribe practices on the part of labor and management which affect commerce and are inimical to the general welfare, and to protect the rights of the public in connection with labor disputes affecting commerce.

The amendments enacted in Taft–Hartley added a list of prohibited actions, or unfair labor practices, on the part of unions to the NLRA, which had previously only prohibited unfair labor practices committed by employers. The Taft–Hartley Act prohibited jurisdictional strikes, wildcat strikes, solidarity or political strikes, secondary boycotts, secondary and mass picketing, closed shops, and monetary donations by unions to federal political campaigns. It also required union officers to sign non-communist affidavits with the government. Union shops were heavily restricted, and states were allowed to pass right-to-work laws that ban agency fees. Furthermore, the executive branch of the federal government could obtain legal strikebreaking injunctions if an impending or current strike imperiled the national health or safety.[11]

Jurisdictional strikes

[edit]In jurisdictional strikes, outlawed by Taft–Hartley, a union strikes in order to assign particular work to the employees it represents. Secondary boycotts and common situs picketing, also outlawed by the act, are actions in which unions picket, strike, or refuse to handle the goods of a business with which they have no primary dispute but which is associated with a targeted business.[12][citation needed] A later statute, the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, passed in 1959, tightened these restrictions on secondary boycotts still further.

Campaign expenditures

[edit]According to First Amendment scholar Floyd Abrams, the act "was the first law barring unions and corporations from making independent expenditures in support of or [in] opposition to federal candidates".[7]

Closed shops

[edit]The law outlawed closed shops which were contractual agreements that required an employer to hire only labor union members. Union shops, still permitted, require new recruits to join the union within a certain amount of time. The National Labor Relations Board and the courts have added other restrictions on the power of unions to enforce union security clauses and have required them to make extensive financial disclosures to all members as part of their duty of fair representation.[citation needed] On the other hand, Congress repealed the provisions requiring a vote by workers to authorize a union shop a few years after the passage of the act when it became apparent that workers were approving them in virtually every case.[citation needed]

Union security clauses

[edit]The amendments also authorized individual states to outlaw union security clauses (such as the union shop) entirely in their jurisdictions by passing right-to-work laws. A right-to-work law, under Section 14B of Taft–Hartley, prevents unions from negotiating contracts or legally binding documents requiring companies to fire workers who refuse to join the union.[citation needed] Currently all of the states in the Deep South and a number of states in the Midwest, Great Plains, and Rocky Mountains regions have right-to-work laws (with six states—Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Oklahoma—going one step further and enshrining right-to-work laws in their states' constitutions).[citation needed]

Strikes and lockouts

[edit]Notice provisions

[edit]The amendments required unions and employers to give 80 days' notice to each other and to certain state and federal mediation bodies before they may undertake strikes or other forms of economic action in pursuit of a new collective bargaining agreement; it did not, on the other hand, impose any "cooling-off period" after a contract expired.

National emergency provisions

[edit]Section 206 of the Act, codified at 29 U.S.C. § 176, also authorized a president to intervene in strikes or lockouts, under certain circumstances, by seeking a court order compelling companies and unions to attempt to continue to negotiate.[13] Under this section, if the president determines that an actual or threatened lockout affects all or a substantial part of an industry engaged in interstate or foreign "trade, commerce, transportation, transmission, or communication" and that the occurrence or continuation of a strike or lockout would "imperil the national health or safety," the President may empanel a board of inquiry to review the issues and issue a report.[13] Upon receiving the report, the president may direct the U.S. Attorney General to seek an injunction from a federal court.[13] If a court enters an injunction, then a strike by workers or a lockout by employers is suspended for an 80-day period; employees must return to work while management and unions must "make every effort to adjust and settle their differences"[13][14] with the assistance of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service.[13] Presidents have invoked this provision 37 times.[14] In 2002, President George W. Bush invoked the law in connection with the employer lockout of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union during negotiations with West Coast shipping and stevedoring companies.[15] This was the first successful invocation of the emergency provisions since President Richard M. Nixon intervened to halt a longshoremen's strike in 1971.[15]

Prohibition on federal employee strikes

[edit]Section 305 of the Act prohibited federal employees from striking.[16] This prohibition was subsequently repealed and replaced by a similar provision, 5 U.S.C. § 7311, which bars any person who "participates in a strike, or asserts the right to strike against the Government of the United States" from federal employment.[17]

Anti-communism

[edit]The amendments required union leaders to file affidavits with the United States Department of Labor declaring that they were not supporters of the Communist Party and had no relationship with any organization seeking the "overthrow of the United States government by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional means" as a condition to participating in NLRB proceedings. Just over a year after Taft–Hartley passed, 81,000 union officers from nearly 120 unions had filed the required affidavits.[10] This provision was at first upheld in the 1950 Supreme Court decision American Communications Ass'n v. Douds, but in 1965, the Supreme Court held that this provision was an unconstitutional bill of attainder.[18]

Treatment of supervisors

[edit]The amendments expressly excluded supervisors from coverage under the act, and allowed employers to terminate supervisors engaging in union activities or those not supporting the employer's stance.[19] The amendments maintained coverage under the act for professional employees, but provided for special procedures before they may be included in the same bargaining unit as non-professional employees.[20]

Right of employer to oppose unions

[edit]The act revised the Wagner Act's requirement of employer neutrality, to allow employers to deliver anti-union messages in the workplace.[5] These changes confirmed an earlier Supreme Court ruling that employers have a constitutional right to express their opposition to unions, so long as they did not threaten employees with reprisals for their union activities nor offer any incentives to employees as an alternative to unionizing. The amendments also gave employers the right to file a petition asking the board to determine if a union represents a majority of its employees, and allow employees to petition either to decertify their union, or to invalidate the union security provisions of any existing collective bargaining agreement.

National Labor Relations Board

[edit]The amendments gave the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board discretionary power to seek injunctions against either employers or unions that violated the act.[citation needed] The law made pursuit of such injunctions mandatory, rather than discretionary, in the case of secondary boycotts by unions.[citation needed] The amendments also established the general counsel's autonomy within the administrative framework of the NLRB. Congress also gave employers the right to sue unions for damages caused by a secondary boycott, but gave the general counsel exclusive power to seek injunctive relief against such activities.[citation needed]

Federal jurisdiction

[edit]The act provided for federal court jurisdiction to enforce collective bargaining agreements. Although Congress passed this section to empower federal courts to hold unions liable in damages for strikes violating a no-strike clause, this part of the act has instead served as the springboard for creation of a "federal common law" of collective bargaining agreements, which favored arbitration over litigation or strikes as the preferred means of resolving labor disputes.[citation needed]

Conciliation Service

[edit]The United States Conciliation Service, which had provided mediation for labor disputes as part of Department of Labor, was removed from that department and reconstituted as an independent agency, the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (United States). This was done in part because industry forces thought the existing service had been too "partial" to labor.[21]

Other

[edit]The Congress that passed the Taft–Hartley Amendments considered repealing the Norris–La Guardia Act to the extent necessary to permit courts to issue injunctions against strikes violating a no-strike clause, but chose not to do so. The Supreme Court nonetheless held several decades later that the act implicitly gave the courts the power to enjoin such strikes over subjects that would be subject to final and binding arbitration under a collective bargaining agreement.

Finally, the act imposed a number of procedural and substantive standards that unions and employers must meet before they may use employer funds to provide pensions and other employee benefit to unionized employees. Congress has since passed more extensive protections for workers and employee benefit plans as part of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act ("ERISA").

Aftermath

[edit]

Union leaders in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) vigorously campaigned for Truman in the 1948 election based upon a (never fulfilled) promise to repeal Taft–Hartley.[22] Truman won, but a union-backed effort in Ohio to defeat Taft in 1950 failed in what one author described as "a shattering demonstration of labor's political weaknesses".[23]

See also

[edit]- Labor unions in the United States

- Norris–La Guardia Act

- Wagner Act

- Jurisdictional strike

- Solidarity action

- Chauffeurs, Teamsters, and Helpers Local No. 391 v. Terry, 494 U.S. 558 (1990) 5 to 2 on §185 of LMRA 1947, holding that a plaintiff is entitled to trial by jury if the trade union denies representation

Notes

[edit]- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 49–51, 57.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Wagner, Steven. "How Did the Taft-Hartley Act Come About?". History News Network.

- ^ Bowen 2011, pp. 49–51.

- ^ a b Anna McCarthy, The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America, New York: The New Press, 2010, p. 54. ISBN 978-1-59558-498-4.

- ^ "June 20, 1947: On the Veto of the Taft-Hartley Bill". Miller Center. 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ^ a b Debating 'Citizens United', The Nation (2011-01-13)

- ^ "National Affairs: Barrel No. 2". Time. June 23, 1947. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Benjamin C. Waterhouise, Lobbying in America, (Princeton University Press, 2013) 53.

- ^ a b Nicholson, Phillip (2004). Labor's Story in the United States. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-239-1.

- ^ Cox, Archibald (February 1960). "Strikes and the Public Interest - A Proposal for New Legislation". The Atlantic.

- ^ 29 U.S.C. §§ 151-169 Section 8(b)(4)

- ^ a b c d e The UAW-Automakers Labor Dispute and Taft-Hartley's National Emergency Provisions, Congressional Research Service (October 2, 2023).

- ^ a b Paul Wiseman, The president could invoke a 1947 law to try to suspend the dockworkers' strike. Here's how, Associated Press (October 2, 2024).

- ^ a b Sanger, David E.; Greenhouse, Steven (October 9, 2002). "President Invokes Taft-Hartley Act To Open 29 Ports". The New York Times.

- ^ Fleischli, George R. (May–June 1968). "DUTY TO BARGAIN UNDER EXECUTIVE ORDER 10988". Air Force Law Review.

- ^ Kurt L. Hanslowe and John L. Acierno, Law and Theory of Strikes by Government Employees, 67 Cornell L. Rev. 1055, 1059 n.16 (1982).

- ^ United States v. Brown (1965), 381 U.S. 437 (Supreme Court June 7, 1965) ("Held: Section 504 constitutes a bill of attainder and is therefore unconstitutional.").

- ^ Gruenberg, Mark (June 11, 2007). "Taft-Hartley Signed 60 Years Ago". Political Affairs Magazine. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ^ PUBLIC LAWS-CHS.114, 120-JUNE 21, 23,1947 (PDF). 80Ta CONG ., 1ST SESS .-CH. 120-JUNE 23, 1947. p. 136.

- ^ Stark, Louis (June 24, 1947). "Analysis of the Labor Act Shows Changed Era at Hand for Industry". The New York Times. pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Davis, Mike (2000). Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 1-85984-248-8.

- ^ Lubell, Samuel (1956). The Future of American Politics (2nd ed.). Anchor Press. p. 202. OL 6193934M.

Works cited

[edit]- Bowen, Michael (2011). The Roots of Modern Conservatism: Dewey, Taft, and the Battle for the Soul of the Republican Party. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9780807869192.

- McCoy, Donald R. (1984). The Presidency of Harry S. Truman. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0252-0.

References

[edit]- Faragher, J.M.; Buhle, M.J.; Czitrom, D.; and Armitage, S.H. Out of Many: A History of the American People. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

- McCann, Irving G. Why the Taft-Hartley Law? New York: Committee for Constitutional Government, 1950.

- Millis, Harry A. and Brown, Emily Clark. From the Wagner Act to Taft-Hartley: A Study of National Labor Policy and Labor Relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1950.

Further reading

[edit]- Caballero, Raymond. McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Labor Management Relations Act (PDF/details) as amended in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Fred A Hartley" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive