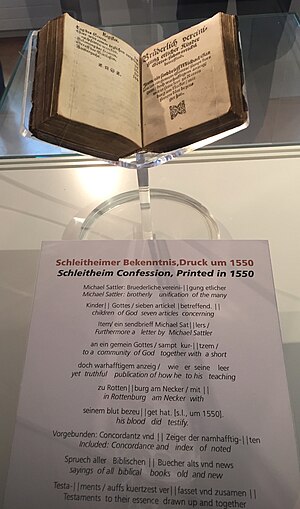

Schleitheim Confession

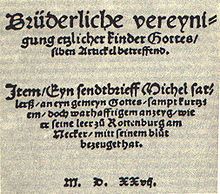

The Schleitheim Confession was the most representative statement of Anabaptist principles, by a group of Swiss Anabaptists in 1527 in Schleitheim, Switzerland. The real title is Brüderliche vereynigung etzlicher Kinder Gottes siben Artickel betreffend ... ("Brotherly Union of a Number of Children of God Concerning Seven Articles").

Origin

[edit]The Confession is believed to have been written by Michael Sattler.[1] The South German Ordnung of approximately the same date is similar to that of the Schleitheim Confession but contains many more Biblical references supporting the confession.[2]: 191 The Schleitheim confession continues to be a guide for churches such as many Schwarzenau Brethren, the Bruderhof and the Hutterites, who trace their spiritual heritage back to the Radical Reformation and the Anabaptists.[3][4]

Doctrine

[edit]The Confession consisted of seven articles, written during a time of severe persecution:[5]

- Baptism

- Baptism is administered only to those who have consciously repented, turned away from sin, amended their lives and believe that Christ has died for their sins and who request it for themselves (believer's baptism). Infant baptism is specifically denounced.

- The Ban (Excommunication)

- A Christian should live with discipline and walk in the way of righteousness, following after Jesus every day. Those members of the Body who slip and fall into sin should be admonished twice in private, but the third offense should be openly disciplined and banned as a final recourse. This should always occur prior to the breaking of the bread, to preserve the unity and purity of the Body of Christ.

- Breaking of Bread (Communion)

- Only those who have been baptized into the Body of Christ are members of the Body, thus only they can take part in the communion of the Body of Christ. Participation in Communion is an observance and remembrance of Christ's body and blood; the physical body and blood of Christ is not believed to be received in the sacrament.[6]

- Separation from Evil

- The community of Christians shall have no association with those who remain in disobedience and a spirit of rebellion against God. There can be no fellowship with the wickedness of this earthly world; therefore there can be no participation in the organizations, works, church services, meetings or civil affairs of those who live in contradiction to the commands of God (this may include Catholics and Protestants as well as other religions and pagans). All evil must be put away, including using weapons of force such as the sword and armor.

- Pastors in the Church

- All elders and leaders in the church must be men of good repute, as described in Scripture. Some of the responsibilities they must faithfully carry out are teaching, public reading of Scripture, disciplining, applying the ban, leading in prayer, and the sacraments. They are to be supported by the church, but must also be disciplined if they sin.

- The Sword (Christian pacifism) – nonresistance

- Violence must not be used in any circumstance. The way of nonviolence is patterned after the example of Christ who never exhibited violence in the face of persecution or as a punishment for sin. A Christian must love their enemies and pray for those who persecute them, as Jesus did. A Christian should not pass judgment in worldly disputes. It is not appropriate for a Christian to serve as a magistrate; a magistrate acts according to the rules of the world and uses force or orders force to be used, not acting according to the rules of heaven; their weapons are worldly, but the weapons of a Christian are spiritual.

- The Oath

- No oaths should be taken because Jesus prohibited the taking of oaths and swearing, teaching rather complete honesty. Testifying or affirming is not the same thing as swearing. When a person bears testimony, they are testifying about the truth and the present, whether it be good or evil.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ J. Philip Wogaman, Douglas M. Strong, Readings in Christian Ethics: A Historical Sourcebook, Westminster John Knox Press, USA, 1996, p. 141

- ^ Estep, William (1996). Eerdmans, William B (ed.). The Anabaptist Story: An Introduction to Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism. Cambridge, UK: Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-0886-8.

- ^ "Guides". Bruderhof. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- ^ "Bruderhof - Fellowship for Intentional Community". Fellowship for Intentional Community. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- ^ Donald B. Kraybill, Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites, JHU Press, USA, 2010, p. 184

- ^ Janz, "The Trial and Martyrdom of Michael Sattler (1527)", The Anabaptists.

- ^ The Schleitheim Confession, Crockett, KY: Rod and Staff Publishers, 1985.

Further reading

[edit]- Philips, Dietrich (October 1945). "The Schleitheim Confession of Faith". The Mennonite Quarterly Review. 19: 248.

- Meihuizen, H. W. (July 1967). "Who Were the False Brethren Mentioned in the Schleitheim Articles?". The Mennonite Quarterly Review. 41 (3): 200–22.[page needed]

- Sattler, Michael (1973). John Howard Yoder (ed.). The Legacy of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press. ISBN 978-0-8361-1187-3. OCLC 379353.

- Snyder, C. Arnold (1984). The Life and Thought of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press. ISBN 978-0-8361-1264-1. OCLC 10230672.[page needed]

- Snyder, C. Arnold (Winter 1985). "The Schleitheim Articles in Light of the Revolution of the Common Man: Continuation or Departure?". Sixteenth Century Journal. 16 (4): 419–430. doi:10.2307/2541218. JSTOR 2541218.

- Ste. Marie, Andrew V. (18 April 2017). Walking in the Resurrection: The Schleitheim Confession in Light of the Scriptures. Sermon on the Mount Publishing. ISBN 978-1-68001-000-8.

External links

[edit]- Schleitheim Confession text

- Commentary on the Confession in Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Brüderlich vereinigung etlicher Kinder Gottes / sieben artikel betreffend The original text of the Schleitheim confession, with scanned images of the pages.