Crimean Tatars

qırımtatarlar, qırımlılar | |

|---|---|

| |

Crimean Tatars in traditional clothes at the Hıdırlez festival | |

| Total population | |

| c. 720,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Ukraine

| 248,193[a] - 300 000[1] |

| Uzbekistan | 239,000[2] |

| Turkey

| 150,000 |

| Romania | 24,137[3] |

| Russia

| 2,449[a][4] |

| Bulgaria | 1,803[5] |

| Kazakhstan | 1,532[6] |

| United States | 500–1,000[7] |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Urums[8] • Crimean Karaites • Lipka Tatars • Krymchaks • Crimean Roma • Dobrujan Tatars • Kumyks • Balkars • Karachays • Turks[9] • Nogais Volga Tatars • | |

| Part of a series on |

| Crimean Tatars |

|---|

| By region or country |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Culture |

| History |

| People and groups |

Crimean Tatars (Crimean Tatar: qırımtatarlar, къырымтатарлар) or Crimeans (Crimean Tatar: qırımlılar, къырымлылар) are an East European Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea.[10] The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars lasted over 2500 years in Crimea and the Northern Black Sea region, uniting Mediterranean populations with those of the Eurasian Steppe.[11][12][10]

Crimean Tatars constituted the majority of Crimea's population from the time of ethnogenesis until the mid-19th century, and the largest ethnic population until the end of the 19th century.[13][14] Russia attempted to purge Crimean Tatars through a combination of physical violence, intimidation, forced resettlement, and legalized forms of discrimination between 1783 and 1900. From Russia's annexation of Crimea in 1783 to 1800, between 100,000 and 300,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated.

While Crimean Tatar cultural elements were not completely eradicated under the Romanov dynasty, the Crimean Tatars were almost completely driven from the Crimean peninsula under the Soviets.[15] Almost immediately after retaking of Crimea from Axis forces, in May 1944, the USSR State Defense Committee ordered the deportation of all of the Crimean Tatars from Crimea, including the families of Crimean Tatars who had served in the Soviet Army. The deportees were transported in trains and boxcars to Central Asia, primarily to Uzbekistan. The Crimean Tatars lost 18–46 percent of their population as a result of the deportations.[16] Starting in 1967, a few were allowed to return and in 1989 the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union condemned the removal of Crimean Tatars from their motherland as inhumane and lawless, but only a tiny percent were able to return before the full right of return became policy in 1989.

The Crimean Tatars have been members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) since 1991.[17] The European Union and international indigenous groups do not dispute their status as an indigenous people and they have been officially recognized as an indigenous people of Ukraine as of 2014.[18][19] The current Russian administration considers them a "national minority", but not an indigenous people,[20][21] and continues to deny that they are titular people of Crimea, even though the Soviet Union considered them indigenous before their deportation and the subsequent dissolution of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Crimean ASSR).[22][23][24][25] Today, Crimean Tatars constitute approximately 15% of the population of Crimea.[26] A Crimean Tatar diaspora remains in Turkey and Uzbekistan.

Language

[edit]The Crimean Tatar language is a member of Kipchak languages of the Turkic language family. It has three dialects and the standard language is written in the central dialect. Crimean Tatar has a unique position among the Turkic languages because its three "dialects" belong to three different (sub)groups of Turkic. This makes the classification of Crimean Tatar as a whole difficult.

UNESCO ranked Crimean Tatar as one of the most endangered languages that are under serious threat of extinction (severely endangered) in 2010.[27][28] However, according to the Institute of Oriental Studies, due to negative situations, the real degree of threat has elevated to critically endangered languages in recent years, which are highly likely to face extinction in the coming generations.[29]

- Noğay, (çöl "desert", şimaliy "northern"): Noğay is spoken by the vast majority of diaspora Crimean Tatars in Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey and others. It belongs to Bulgar subgrouping of the Kipchak family and Nogai, another Kipchak language, has influenced it. It is related to Kazakh, Karakalpak, and Nogai proper. This dialect was spoken by former nomadic inhabitants of the Crimean steppes. It has roots in Cumania and later the Golden Horde.[30] It was influenced by the Middle Mongol spoken in the Golden Horde and notable Slavic influences occurred during the Imperial Russian invasion in 1783.[31]

- Bağçasaray (orta yolaq "middle region"): Standard Crimean Tatar is classified as a language of the Cuman subgroup of Kipchak and the closest relatives are Karachay-Balkar, Karaim, and Urum. Bağçasaray is spoken in Crimea by sedentary Tatars as the standard language because its speakers comprise a relative majority of Crimean Tartar speakers in Crimea. The middle dialect, although it is a Kipchak language, has strong Turkish, Ukrainian, Mariupol Greek (especially Urum language) elements.[32]

- Yalıboyu (cenübiy "Southern"): The Yalıboyu, Tat-Tarter, or Coastal Tatar language is an Oghuz language descended from Ottoman Turkish.[33] It arrived in Crimea through the Ottoman Empire's conquest of the Principality of Theodoro in 1475.[34] Following the Turkish occupation, Southern Crimea came under direct Ottoman Turkish rule, while the Crimean Khanate in northern regions was vassalized. The language has possible Crimean Gothic and some Italian and Greek influences due to trade routes.[35]

Sub-ethnic groups

[edit]

The Crimean Tatars are subdivided into six sub-ethnic groups:

- The Mountain Tats (not to be confused with the Iranic Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the mountainous Crimea before 1944 predominantly are Cumans, Greeks, Goths and other people, as Tats in Crimea also were called Hellenic Urum people (Greeks settled in Crimea) who were deported by the Imperial Russia to the area around Mariupol;[36] The term Tat appears already in the 8th century Orkhon inscriptions denoting "a subjected foreign people". In the 17th century Crimean context, it probably denoted various peoples of foreign (ie. non-Turkic) origin living under the khan's rule, especially the Greeks, Italians, and the remnants of Goths and Alans inhabiting the mountainous southern section of Crimea.[37][38]

- The Yaliboylu Tats composed of Tatarized descendants of peoples who lived on the Southern Coast of the peninsula before 1944 and practiced Christianity until the 14th century;[36]

- The Noğay Tatars (not to be confused with related Nogai people, living now in Southern Russia) — former inhabitants of the Crimean steppe.[36]

- The Tajfa who are Roma Muslims assimilated into the Crimean Tatar people, speak a Crimean Tatar dialect, and typically consider themselves to be Crimean Tatar first and Roma as a secondary identity.[39][40]

- The Urum: A group of Turkic-speaking Greek Orthodox people native to Crimea, who have assimilated over time. They are closely related to the Ukrainian Greeks and are traditionally believed to be descendants of ancient Crimean Greeks who later had direct contact with the Crimean Khanate.[41][42]

- The Lipka Tatars. Part of the Lipka Tatars, who came from the Crimean Khanate, are considered part of the Crimean Tatars.[43][44] They played a significant role in the Crimean Tatar national movement during the First and Second World Wars (Maciej Sulkiewicz, Mustafa Edige Kirimal, Olgerd Krychynsky).[45] Famous scientists and writers with a world name come from Lipka Tatars (Henryk Sienkiewicz, Ahatanhel Krymsky and Mykhailo Tugan-Baranovsky). Most of them do not know the Crimean Tatar language due to assimilation and speak Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian.

Historians suggest that inhabitants of the mountainous parts of Crimea lying to the central and southern parts (the Tats), and those of the Southern coast of Crimea (the Yalıboyu) were the direct descendants of the Pontic Greeks, Scythians, Ostrogoths (Crimean Goths), and Kipchaks along with the Cumans while the latest inhabitants of the northern steppe represent the descendants of the Nogai Horde of the Black Sea, nominally subjects of the Crimean Khan.[46][47] It is largely assumed that the Tatarization process that mostly took place in the 16th century brought a sense of cultural unity through the blending of the Greeks, Italians, Ottoman Turks of the southern coast, Goths of the central mountains and Turkic-speaking Kipchaks and Cumans of the steppe and forming of the Crimean Tatar ethnic group.[48][49][50][51][52] However, the Cuman language is considered the direct ancestor of the current language of the Crimean Tatars with possible incorporations of the other languages, like Crimean Gothic.[53][54][55][56] The fact that Crimean Tatars' ethnogenesis took place in Crimea and consisted of several stages lasting over 2500 years is proved by genetic research showing that the gene pool of the Crimean Tatars preserved both the initial components for more than 2.5 thousand years, and later in the northern steppe regions of the Crimea.[57][58][59]

The Mongol conquest of the Kipchaks led to a merged society with a Mongol ruling class over a Kipchak speaking population which came to be dubbed Tatar and which eventually absorbed other ethnicities on the Crimean peninsula like Italians, Greeks, and Goths to form the modern day Crimean Tatar people; up to the Soviet deportation, the Crimean Tatars could still differentiate among themselves between Tatar, Kipchak, Nogays, and the "Tat" descendants of Tatarized Goths and other Turkified peoples.[60]

- Crimean Tatars of different sub-ethnic groups

-

Crimean Tatar, 1700.

-

Mountain Crimean Tatars, 1820s-1830s, D. K. Bonatti.

-

Nogai Tatars. Russian engraving, beginning of the 19th century.

-

Family of Crimean Tatars. French engraving, 1840s.

-

Crimean Tatar girl, Kapsikhor, XIX century, by Gustav Radde.

-

Crimean Tatar girls in Alupka, 1889, by Kostyantin Trutovsky.

-

Crimean Tatars girls, XIX century.

-

Crimean Tatar girls, a collection of photographs of pre-revolutionary Russia.

-

Crimean Tatar noble woman with children, 1925.

-

Lipka Tatars, 2021.

Genetics

[edit]The genetic composition of the Crimean Tatars is distinguished by the presence of two predominant patterns: the so-called "sea pattern" and the "steppe pattern". The former is believed to have originated from Mediterranean populations,[61] while the latter is attributed to the nomadic tribes of the Great Eurasian steppe.[62][63][64] The primary contributor to the "sea pattern" of the Crimean Tatars is not the later migrations of Greeks from the Byzantine Empire, but rather the ancient populations from the city-states of the Eastern Mediterranean dating back to the 7th to 5th centuries BC. This assertion is further substantiated by the analysis of the Crimean Tatar gene pool as revealed by the Human Origins full-genome panel data.[65] Geneticists have concluded that the Crimean Tatars, as a distinct ethnic group, were formed directly within Crimea, rather than migrating to the region, thereby affirming their status as the indigenous inhabitants of Crimea.[62][66]

Contrary to hypotheses suggesting that the gene pool of the Crimean Tatars was significantly influenced by Central Asian populations or Mongolic groups, genetic research indicates a considerable divergence from both,[67] with the Balkars, a highland ethnic group from the Caucasus, being most genetically akin to the Crimean Tatars.[64][68] Furthermore, the hypothesis positing a substantial impact of Slavic populations on the genetic makeup of the Crimean Tatars is also refuted by genetic studies, which reveal no significant influx of "Slavic" genetic material into the Crimean Tatar gene pool despite prolonged proximity.[69]

The preliminary phase of the comprehensive analysis of complete Y-chromosomes, undertaken at the Laboratory of Genomic Geography of the N. I. Vavilov Institute of General Genetics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, focused on three specific haplogroups — G1, N3, and R1b — unveiled connections between the Crimean Tatars and the genomes of individuals from the Bronze Age steppes of Eurasia, specifically those associated with the Yamnaya archaeological culture, and the "European" (N3a3) and "Asian" (N3a5) Neolithic variants of haplogroup N3 in Northern Eurasia. These findings may reflect not only the genetic legacy of the Scythians and Sarmatians but also more ancient affiliations between the populations of mainland Eastern Europe and the Crimean Peninsula.[70]

The genetic composition of the Crimean Tatars is primarily constituted by five predominant haplogroups: R1a, R1b, J2, G2a3b1 and E1b1b1, which together account for 67% of the genetic diversity, whereas other haplogroups are classified as minor, each contributing between 1% and 5% to the overall genetic makeup of the Crimean Tatars.[64]

-

Ancestral populations of Crimean Tatars based on mitochondrial DNA compared to Central Asian populations [Comas et al., 2004].[73]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The Crimean Tatars were formed as a people in Crimea and are descendants of various peoples who lived in Crimea in different historical eras. The main ethnic groups that inhabited the Crimea at various times and took part in the formation of the Crimean Tatar people are Tauri, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Ancient Greeks, Crimean Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Khazars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Italians. The consolidation of this diverse ethnic conglomerate into a single Crimean Tatar people took place over the course of centuries. The connecting elements in this process were the commonality of the territory, the Turkic language and Islamic religion.[76][77][10][64]

By the end of the 15th century, the main prerequisites that led to the formation of an independent Crimean Tatar ethnic group were created: the political dominance of the Crimean Khanate was established in Crimea, the Turkic languages (Cuman-Kipchak on the territory of the khanate) became dominant, and Islam acquired the status of a state religion throughout the Peninsula. By a preponderance Cumanian population of the Crimea acquired the name "Tatars", the Islamic religion and Turkic language, and the process of consolidating the multi-ethnic conglomerate of the Peninsula began, which has led to the emergence of the Crimean Tatar people.[23] Over several centuries, on the basis of Cuman language with a noticeable Oghuz influence, the Crimean Tatar language has developed.[78][79][80][81]

In the Golden Horde

[edit]

At the beginning of the 13th century in the Crimea, the majority of the population, which was already composed of a Turkic people — Cumans, became a part of the Golden Horde. The Crimean Tatars mostly adopted Islam in the 14th century and thereafter Crimea became one of the centers of Islamic civilization in Eastern Europe. In the same century, trends towards separatism appeared in the Crimean Ulus of the Golden Horde. De facto independence of the Crimea from the Golden Horde may be counted since the beginning of princess (khanum) Canike's, the daughter of the powerful Khan of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh and the wife of the founder of the Nogai Horde Edigey, reign in the peninsula. During her reign she strongly supported Hacı Giray in the struggle for the Crimean throne until her death in 1437. Following the death of Canike, the situation of Hacı Giray in Crimea weakened and he was forced to leave Crimea for Lithuania.[82]

The Crimean Tatars emerged as a nation at the time of the Crimean Khanate, an Ottoman vassal state during the 16th to 18th centuries.[83] Russian historian, doctor of history, Professor of the Russian Academy of Sciences Ilya Zaytsev writes that analysis of historical data shows that the influence of Turkey on the policy of the Crimea was not as high as it was reported in old Turkish sources and Imperial Russian ones.[84] The Turkic-speaking population of Crimea had mostly adopted Islam already in the 14th century, following the conversion of Ozbeg Khan of the Golden Horde.[85] By the time of the first Russian invasion of Crimea in 1736, the Khan's archives and libraries were famous throughout the Islamic world, and under Khan Krym-Girei the city of Aqmescit was endowed with piped water, sewerage and a theatre where Molière was performed in French, while the port of Kezlev stood comparison with Rotterdam and Bakhchysarai, the capital, was described as Europe's cleanest and greenest city.[86]

In the Crimean Khanate

[edit]

In 1441, an embassy from the representatives of several strongest clans of the Crimea, including the Golden Horde clans Shırın and Barın and the Cumanic clan — Kıpçak, went to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to invite Hacı Giray to rule in the Crimea. He became the founder of the Giray dynasty, which ruled until the annexation of the Crimean Khanate by Russia in 1783.[87] Hacı I Giray was a Jochid descendant of Genghis Khan and of his grandson Batu Khan of the Golden Horde. During the reign of Meñli I Giray, Hacı's son, the army of the Great Horde that still existed then invaded the Crimea from the north, Crimean Khan won the general battle, overtaking the army of the Horde Khan in Takht-Lia, where he was killed, the Horde ceased to exist, and the Crimean Khan became the Great Khan and the successor of this state.[87][88] Since then, the Crimean Khanate was among the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.[89] The Khanate officially operated as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, with great autonomy after 1580.[90] At the same time, the Nogai hordes, not having their own khan, were vassals of the Crimean one, Muskovy and Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth[91][92] paid annual tribute to the khan (until 1700[93] and 1699 respectively). In the 17th century, the Crimean Tatars helped Ukrainian Cossacks led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky in the struggle for independence, which allowed them to win several decisive victories over Polish troops.[94]

In 1711, when Peter I of Russia went on a campaign with all his troops (80,000) to gain access to the Black Sea, he was surrounded by the army of the Crimean Khan Devlet II Giray, finding himself in a hopeless situation. And only the betrayal of the Ottoman vizier Baltacı Mehmet Pasha allowed Peter to get out of the encirclement of the Crimean Tatars.[95] When Devlet II Giray protested against the vizier's decision,[96] his response was: "You should know your Tatar affairs. The affairs of the Sublime Porte are entrusted to me. You do not have the right to interfere in them".[97] Treaty of the Pruth was signed, and 10 years later, Russia declared itself an empire. In 1736, the Crimean Khan Qaplan I Giray was summoned by the Turkish Sultan Ahmed III to Persia. Understanding that Russia could take advantage of the lack of troops in Crimea, Qaplan Giray wrote to the Sultan to think twice, but the Sultan was persistent. As it was expected by Qaplan Giray, in 1736 the Russian army invaded the Crimea, led by Münnich, devastated the peninsula, killed civilians and destroyed all major cities, occupied the capital, Bakhchisaray, and burnt the Khan's palace with all the archives and documents, and then left the Crimea because of the epidemic that had begun in it. One year after the same was done by another Russian general — Peter Lacy.[87][98] Since then, the Crimean Khanate had not been able to recover, and its slow decline began. The Russo-Turkish War of 1768 to 1774 resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and the Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea, Imperial Russia violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783.

The main population of the Crimean khanate were Crimean Tatars, along with them in the Crimean khanate lived significant communities of Karaites, Italians, Armenians, Greeks, Circassians and Roma. In the early 16th century under the rule of the Crimean khans passed part of Nogays (Mangyts), who roamed outside the Crimean Peninsula, moving there during periods of drought and starvation. The majority of the population professed Islam of the Hanafi stream; part of the population – Orthodox, Monotheletism, Judaism; in the 16th century. There were small Catholic communities. The Crimean Tatar population of the Crimean Peninsula was partially exempt from taxes. The Greeks paid dzhyziya, the Italians were in a privileged position due to the partial tax relief made during the reign of Meñli Geray I. By the 18th century the population of the Crimean khanate was about 500 thousand people. The territory of the Crimean khanate was divided into Kinakanta (governorships), which consisted of Kadylyk, covering a number of settlements.[99]

Nogay slave trade (15th–18th centuries)

[edit]Until the beginning of the 18th century, the Crimean Nogays were known for frequent, at some periods almost annual, slave raids into present-day 'mainland' Ukraine and Russia.[100][101][83][102] For a long time, until the late 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East which was one of the important factors of its economy.[99][103] One of the most important trading ports and slave markets was Kefe.[104][105] According to the Ottoman census of 1526, taxes on the sale and purchase of slaves accounted for 24% of the funds, levied in Ottoman Crimea for all activities.[106] But in fact, there were always small raids committed by both Tatars and Cossacks, in both directions.[107] The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi wrote that there were 920,000 Ukrainian slaves in the Crimea but only 187,000 free Muslims.[83] However, the Ukrainian historian Sergey Gromenko considers this testimony of Çelebi a myth popular among ultranationalists, pointing out that today it is known from the writings on economics that in the 17th century, the Crimea could feed no more than 500 thousand people.[108] For comparison, according to the notes of the Consul of France to Qırım Giray khan Baron Totta, a hundred years later, in 1767, there were 4 million people living in the Crimean khanate,[109] and in 1778, that is, just eleven years later, all the Christians were evicted from its territory by the Russian authorities, which turned out to be about 30 thousand,[110] mostly Armenians and Greeks, and there were no Ukrainians among them. Also, according to more reliable modern sources than Evliya's data, slaves never constituted a significant part of the Crimean population.[111] Russian professor Glagolev writes that there were 1.800.000 free Crimean Tatars in the Crimean Khanate in 1666,[112] it also should be mentioned that a huge part of Ukraine was part of the Crimean Khanate, that is why Ukrainians could have been taken into account in the general population of the Khanate by Evliya (see Khan Ukraine).

Some researchers estimate that more than 2 million people were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate. Polish historian Bohdan Baranowski assumed that in the 17th century Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (present-day Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus) lost an average of 20,000 yearly and as many as one million in all years combined from 1500 to 1644.[83][113] One of the most famous victims of the Tatar slave trade was a young woman from Ruthenia, captured during her wedding who came to be known as Roxelana (Hürrem Sultan), a concubine of Sultan Suleiman.

In retaliation, the lands of Crimean Tatars were being raided by Zaporozhian Cossacks,[107] armed Ukrainian horsemen, who defended the steppe frontier – Wild Fields – against Tatar slave raids and often attacked and plundered the lands of Ottoman Turks and Crimean Tatars. The Don Cossacks and Kalmyk Mongols also managed to raid Crimean Tatars' land.[114] The last recorded major Crimean raid, before those in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) took place during the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725).[107] However, Cossack raids continued after that time; Ottoman Grand Vizier complained to the Russian consul about raids to Crimea and Özi in 1761.[107] In 1769 one last major Tatar raid, which took place during the Russo-Turkish War, saw the capture of 20,000 slaves.[103]

Nevertheless, some historians, including Russian historian Valery Vozgrin and Polish historian Oleksa Gayvoronsky have emphasized that the role of the slave trade in the economy of the Crimean Khanate is greatly exaggerated by modern historians, and the raiding-dependent economy is nothing but a historical myth.[115][116] According to modern researches, livestock occupied a leading position in the economy of the Crimean Khanate, Crimean Khanate was one of the main wheat suppliers to the Ottoman Empire. Salt mining, viticulture and winemaking, horticulture and gardening were also developed as sources of income.[99]

Several modern historians have argued that historiography on the Crimean Tatars has been strongly influenced by Russian historians, who have rewritten the history of the Crimean Khanate to justify the annexation of Crimea in 1783, and, especially, then by Soviet historians who distorted the history of Crimea to justify the 1944 deportation of the Crimean Tatars.[117][118][119][120][121]

In the Russian Empire

[edit]

The Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and the Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea, Russia violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783. After the annexation, the wealthier Tatars, who had exported wheat, meat, fish and wine to other parts of the Black Sea, began to be expelled and to move to the Ottoman Empire. Due to the oppression by the Russian administration and colonial politics of Russian Empire, the Crimean Tatars were forced to immigrate to the Ottoman Empire. Further expulsions followed in 1812 for fear of the reliability of the Tatars in the face of Napoleon's advance. Particularly, the Crimean War of 1853–1856, the laws of 1860–63, the Tsarist policy and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) caused an exodus of the Tatars; 12,000 boarded Allied ships in Sevastopol to escape the destruction of shelling, and were branded traitors by the Russian government.[86] Of total Tatar population 300,000 of the Taurida Governorate about 200,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated.[122] Many Crimean Tatars perished in the process of emigration, including those who drowned while crossing the Black Sea. In total, from 1783 till the beginning of the 20th century, at least 800 thousand Tatars left Crimea. Today the descendants of these Crimeans form the Crimean Tatar diaspora in Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

Ismail Gasprali (1851–1914) was a renowned Crimean Tatar intellectual, influenced by the nationalist movements of the period, whose efforts laid the foundation for the modernization of Muslim culture and the emergence of the Crimean Tatar national identity. The bilingual Crimean Tatar-Russian newspaper Terciman-Perevodchik he published in 1883–1914, functioned as an educational tool through which a national consciousness and modern thinking emerged among the entire Turkic-speaking population of the Russian Empire.[86] After the Russian Revolution of 1917 this new elite, which included Noman Çelebicihan and Cafer Seydamet Qırımer proclaimed the first democratic republic in the Islamic world, named the Crimean People's Republic on 26 December 1917. However, this republic was short-lived and abolished by the Bolshevik uprising in January 1918.[123]

- Crimea and Crimean Tatars in History

-

Caffa in ruins (1788) after Russian annexation of Crimea

-

Abandoned houses in Qarasuvbazar.

-

The Crimean Tatar national dance, Qaytarma (1790s)

-

Crimean Tatar squadron of the Russian Empire (1850)

-

Crimean Tatar archer (Wacław Pawliszak, c. 1890)

-

Kurultay of the Crimean Tatar People, 1917

In the Soviet Union (1917–1991)

[edit]

As a part of the Russian famine of 1921 the Peninsula suffered widespread starvation.[124] More than 100,000 Crimean Tatars starved to death,[124] and tens of thousands of Tatars fled to Turkey or Romania.[125] Thousands more were deported or killed during the collectivization in 1928–29.[125] The Soviet government's "collectivization" policies led to a major nationwide famine in 1931–33. Between 1917 and 1933, 150,000 Tatars—about 50% of the population at the time—either were killed or forced out of Crimea.[126] During Stalin's Great Purge, statesmen and intellectuals such as Veli İbraimov and Bekir Çoban-zade were imprisoned or executed on various charges.[125]

In May 1944, the entire Crimean Tatar population of Crimea was exiled to Central Asia, mainly to Uzbekistan, on the orders of Joseph Stalin, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Chairman of the USSR State Defense Committee. Although a great number of Crimean Tatar men served in the Red Army and took part in the partisan movement in Crimea during the war, the existence of a Tatar Legion in the Nazi army and the collaboration of some Crimean Tatar religious and political leaders with Hitler during the German occupation of Crimea provided the Soviet leadership with justification for accusing the entire Crimean Tatar population of being Nazi collaborators. Some modern researchers argue that Crimea's geopolitical position fueled Soviet perceptions of Crimean Tatars as a potential threat.[127] This belief is based in part on an analogy with numerous other cases of deportations of non-Russians from boundary territories, as well as the fact that other non-Russian populations, such as Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians were also removed from Crimea (see Deportation of the peoples inhabiting Crimea).

All 240,000 Crimean Tatars were deported en masse, in a form of collective punishment, on 17–18 May 1944 as "special settlers" to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and other distant parts of the Soviet Union.[128] This event is called Sürgün in the Crimean Tatar language; the few who escaped were shot on sight or drowned in scuttled barges, and within months half their number had died of cold, hunger, exhaustion and disease.[86] Many of them were re-located to toil as forced labourers in the Soviet Gulag system.[129]

Civil rights movement

[edit]Starting in 1944, Crimean Tatars lived mostly in Central Asia with the designation as "special settlers", meaning that they had few rights. "Special settlers" were forbidden from leaving small designated areas and had to frequently sign in at a commandant's office.[130][131][132][133] Soviet propaganda directed towards Uzbeks depicted Crimean Tatars as threats to their homeland, and as a result there were many documented hate crimes against Crimean-Tatar civilians by Uzbek Communist loyalists.[134][135] In the 1950s the "special settler" regime ended, but Crimean Tatars were still kept closely tethered to Central Asia; while other deported ethnic groups like the Chechens, Karachays, and Kalmyks were fully allowed to return to their native lands during the Khrushchev thaw, economic and political reasons combined with basic misconceptions and stereotypes about Crimean Tatars led to Moscow and Tashkent being reluctant to allow Crimean Tatars the same right of return; the same decree that rehabilitated other deported nations and restored their national republics urged Crimean Tatars who wanted a national republic to seek "national reunification" in the Tatar ASSR in lieu of restoration of the Crimean ASSR, much to the dismay of Crimean Tatars who bore no connection to or desire to "return" to Tatarstan.[135][136] Moscow's refusal to allow a return was not only based on a desire to satisfy the new Russian settlers in Crimea, who were very hostile to the idea of a return and had been subject to lots of Tatarophobic propaganda, but for economic reasons: high productivity from Crimean Tatar workers in Central Asia meant that letting the diaspora return would take a toll on Soviet industrialization goals in Central Asia.[131] Historians have long suspected that violent resistance to confinement in exile from Chechens led to further willingness to let them return, while the non-violent Crimean Tatar movement did not lead to any desire for Crimean Tatars to leave Central Asia. In effect, the government was punishing Crimean Tatars for being Stakhanovites while rewarding the deported nations that contributed less to the building of socialism, creating further resentment.[137][138]

A 1967 Soviet decree removed the charges against Crimean Tatars on paper while simultaneously referring to them not by their proper ethnonym but by the euphemism that eventually became standard of "citizens of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in Crimea", angering many Crimean Tatars who realized it meant they were not even seen as Crimean Tatars by the government. In addition, the Soviet government did nothing to facilitate their resettlement in Crimea and to make reparations for lost lives and confiscated property.[139] Before the mass return in the perestroika era, Crimean Tatars made up only 1.5% of Crimea's population, since government entities at all levels took a variety of measures beyond the already-debilitating residence permit system to keep them in Central Asia.[140][141]

The abolition of the special settlement regime made it possible for Crimean Tatar rights activists to mobilize. The primary method of raising grievances with the government was petitioning. Many for the right of return gained over 100,000 signatures; although other methods of protest were occasionally used, the movement remained completely non-violent.[142][143] When only a small percentage of Crimean Tatars were allowed to return to Crimea, those who were not granted residence permits would return to Crimea and try to live under the radar. However, the lack of a residence permit resulted in a second deportation for them. A last-resort method to avoid a second deportation was self-immolation, famously used by Crimean Tatar national hero Musa Mamut, one of those who moved to Crimea without a residence permit. He doused himself with gasoline and committed self-immolation in front of police trying to deport him on 23 June 1978. Mamut died of severe burns several days later, but expressed no regret for having committed self-immolation.[143] Mamut posthumously became a symbol of Crimean Tatar resistance and nationhood, and remains celebrated by Crimean Tatars.[144] Other notable self-immolations in the name of the Crimean Tatar right of return movement include that of Shavkat Yarullin, who fatally committed self-immolation in front of a government building in protest in October 1989, and Seidamet Balji who attempted self-immolation while being deported from Crimea in December that year but survived.[145] Many other famous Crimean Tatars threatened government authorities with self-immolation if they continued to be ignored, including Hero of the Soviet Union Abdraim Reshidov. In the later years of the Soviet Union, Crimean Tatar activists held picket protests in Red Square.[146][133]

After a prolonged effort of lobbying by the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, the Soviet government established a commission in 1987 to evaluate the request for the right of return, chaired by Andrey Gromyko.[147] Gromyko's condescending attitude[148] and failure to assure them that they would have the right of return[149] ended up concerning members of the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement. In June 1988 he issued an official statement that rejected the request for re-establishment of a Crimean Tatar autonomy in Crimea and supported only allowing an organized return of a few more Crimean Tatars, while agreeing to allow the lower-priority requests of having more publications and school instruction in the Crimean Tatar language at the local level among areas with the deported populations.[150] The conclusion that "no basis to renew autonomy and grant Crimean Tatars the right to return"[151] triggered widespread protests.[152] Less than two years after Gromyko's commission had rejected their request for autonomy and return, pogroms against the deported Meskhetian Turks were taking place in Central Asia. During the pogroms, some Crimean Tatars were targeted as well, resulting in changing attitudes towards allowing Crimean Tatars to move back to Crimea.[153] Eventually a second commission, chaired by Gennady Yanaev and inclusive of Crimean Tatars on the board, was established in 1989 to reevaluate the issue, and it was decided that the deportation was illegal and the Crimean Tatars were granted the full right to return, revoking previous laws intended to make it as difficult as possible for Crimean Tatars to move to Crimea.[154][155]

In independent Ukraine (1991–2014)

[edit]Today, more than 250,000 Crimean Tatars have returned to their homeland, struggling to re-establish their lives and reclaim their national and cultural rights against many social and economic obstacles. One-third of them are atheists, and over half that consider themselves religious are non-observant.[156] As of 2009, only 15 out of 650 schools in Crimea provided education in the Crimean Tatar language, and 13 of them only do so in the first three grades.[157]

Squatting in Crimea has been a significant method for Crimean Tatars to rebuild communities in Crimea destroyed by the deportations. These squats have sometimes resulted in violence by Crimean Russians, such as the 1992 Krasny Ray events, in which the security forces of the separatist Republic of Crimea (not to be confused with the post-2014 government of the same name) attacked a Crimean Tatar squat near the village of Krasny Ray. As a result of the attack on the Krasny Ray settlement, Crimean Tatars stormed the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea, leading to the release of 26 squatters who had been abducted by the Crimean security forces.[158]

Crimean Tatars were recognised as an indigenous people by the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine, and granted a limited number of seats in the 1994 Crimean parliamentary election. Nonetheless, they faced constant discrimination from the authorities of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, which was primarily governed by ethnic Russians and directed towards Russian interests.[158] Under the presidency of Viktor Yushchenko, increased attention was paid to Crimean Tatars, with trials for crimes against humanity beginning for those involved in the deportations.[157] However, issues of land failed to be resolved.[159]

2014 annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

[edit]

Following news of Crimea's independence referendum organized with the help of Russia on 16 March 2014, the Kurultai leadership voiced concerns of renewed persecution, as commented by a U.S. official before the visit of a UN human rights team to the peninsula.[160] At the same time, Rustam Minnikhanov, the president of Tatarstan was dispatched to Crimea to quell Crimean Tatars' concerns and to state that "in the 23 years of Ukraine's independence the Ukrainian leaders have been using Crimean Tatars as pawns in their political games without doing them any tangible favors". The issue of Crimean Tatar persecution by Russia has since been raised regularly on an international level.[161][162]

On 18 March 2014, the day Crimea was annexed by Russia, and Crimean Tatar was de jure declared one of the three official languages of Crimea. It was also announced that Crimean Tatars will be required to relinquish coastal lands on which they squatted since their return to Crimea in the early 1990s and be given land elsewhere in Crimea. Crimea stated it needed the relinquished land for "social purposes", since part of this land is occupied by the Crimean Tatars without legal documents of ownership.[163] The situation was caused by the inability of the USSR (and later Ukraine) to sell the land to Crimean Tatars at a reasonable price instead of giving back to the Tatars the land owned before deportation, once they or their descendants returned from Central Asia (mainly Uzbekistan). As a consequence, some Crimean Tatars settled as squatters, occupying land that was and is still not legally registered.

Some Crimean Tatars fled to Mainland Ukraine due to the annexation of Crimea – reportedly around 2,000 by 23 March.[164] On 29 March 2014, an emergency meeting of the Crimean Tatars representative body, the Kurultai, voted in favor of seeking "ethnic and territorial autonomy" for Crimean Tatars using "political and legal" means. The meeting was attended by the Head of the Republic of Tatarstan and the chair of the Russian Council of Muftis.[165] Decisions as to whether the Tatars will accept Russian passports or whether the autonomy sought would be within the Russian or Ukrainian state have been deferred pending further discussion.[166] As of 2016[update], the Mejlis worked in emergency mode in Kyiv.[167]

After the annexation of Crimea by Russian Federation, Crimean Tatars were persecuted and discriminated by Russian authorities, including cases of torture, arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances by Russian security forces and courts.[168][169][170]

On 12 June 2018, Ukraine lodged a memorandum consisting of 17,500 pages of text in 29 volumes to the UN's International Court of Justice about racial discrimination against Crimean Tatars by Russian authorities in occupied Crimea and state financing of terrorism by Russian Federation in Donbas.[171][172]

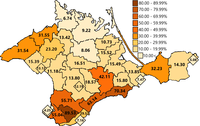

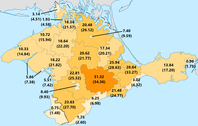

Distribution

[edit]In the 2001 Ukrainian census, 248,200 Ukrainian citizens identified themselves as Crimean Tatars with 98% (or about 243,400) of them living in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.[173][174] An additional 1,800 (or about 0.7%) lived in the city of Sevastopol, also on the Crimean peninsula, but outside the border of the autonomous republic.[173] This territory was annexed by Russia in 2014.

About 150,000 remain in exile in Central Asia, mainly in Uzbekistan. According to Tatar activists, Eskişehir Province houses about 150,000 Crimean Tatars. Some activists set the national level figure as high as 6 million, which is considered an overestimation.[175] Crimean Tatars in Turkey mostly live in Eskişehir Province, descendants of those who emigrated in the late 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.[175] The Dobruja region of Romania and Bulgaria is home to more than 27,000 Crimean Tatars, with the majority in Romania and approximately 3,000 on the Bulgarian side of the border.[3]

Culture

[edit]

Yurts or nomadic tents have traditionally played an important role in the cultural history of Crimean Tatars. There are different types of yurts; some are large and collapsible, called "terme", while others are small and non-collapsible (otav).

Two types of alphabet are in use: Cyrillic and Latin. Initially Crimean Tatars used Arabic script. In 1928, it was replaced with the Latin alphabet. Cyrillic was introduced in 1938 based on the Russian alphabet. The Cyrillic alphabet was the only official one between 1938 and 1997. All its letters coincide with those of the Russian alphabet. The 1990s saw the start of the gradual transition of the language to the new Latin alphabet based on the Turkish one.[176]

The songs (makam) of the nomadic steppe Crimean Tatars are characterized by diatonic, melodic simplicity and brevity. The songs of mountainous and southern coastal Crimean Tatars, called Crimean Tatar: Türkü, are sung with richly ornamented melodies. Household lyricism is also widespread. Occasionally, song competitions take place between young men and women during Crimean holidays and weddings. Ritual folklore includes winter greetings, wedding songs, lamentations and circular dance songs (khoran). Epic stories or destans are very popular among the Crimean Tatars, particularly the destans of "Chora batyr", "Edige", "Koroglu", and others.[177]

On the Nowruz holiday, Crimean Tatars usually cook eggs, chicken soup, puff meat pie (kobete), halva, and sweet biscuits. Children put on masks and sing special songs under the windows of their neighbours, receiving sweets in return.

The traditional cuisine of the Crimean Tatars has similarities with that of Greeks, Italians, Balkan peoples, Nogays, North Caucasians, and Volga Tatars, although some national dishes and dietary habits vary between different Crimean Tatar regional subgroups; for example, fish and produce are more popular among Yaliboylu Tatar dishes while meat and dairy is more prevalent in Steppe Tatar cuisine. Many Uzbek dishes were incorporated into Crimean Tatar national cuisine during exile in Central Asia since 1944, and these dishes have become prevalent in Crimea since the return. Uzbek samsa, laghman, and Crimean Tatar: plov (pilaf) are sold in most Tatar roadside cafes in Crimea as national dishes. In turn, some Crimean Tatar dishes, including chibureki, have been adopted by peoples outside Crimea, such as in Turkey and the North Caucasus.[178]

Crimean Tatar political parties

[edit]National movement of Crimean Tatars

[edit]Founded by Crimean Tatar civil rights activist Yuri Osmanov, the National Movement of Crimean Tatars (NDKT) was the major opposition faction to the Dzhemilev faction during the Soviet era. The official goal of the NDKT during the Soviet era was the restoration of the Crimean ASSR under the Leninist principle of national autonomy for titular indigenous peoples in their homeland, conflicting with the desires of an independent Tatar state from the OKND, the predecessor of the Mejilis. Yuri Osmanov, founder of the organization, was highly critical of Dzhemilev, saying that the OKND, the predecessor of the Mejilis, did not sufficiently try to mend ethnic tensions in Crimea. However, the OKND decreased in popularity after Yuri Osmanov was killed.[179][180][181]

Mejlis

[edit]In 1991, the Crimean Tatar leadership founded the Kurultai, or Parliament, to act as a representative body for the Crimean Tatars which could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies.[182] Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is the executive body of the Kurultai.

From the 1990s until October 2013, the political leader of the Crimean Tatars and the chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People was former Soviet dissident Mustafa Dzhemilev. Since October 2013 the chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People has been Refat Chubarov.[183]

Following the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, Russian authorities declared the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People an extremist organization, and banned it on 26 April 2016.[184]

New Milliy Firqa

[edit]In 2006, a new Crimean Tatar party in opposition to the Mejlis was founded, taking the name of the previously-defunct Milly Firqa party from the early 20th century. The party claims to be successor of the ideas of Yuri Osmanov and NDKT.[185]

Notable Crimean Tatars

[edit]See also

[edit]- Index of articles related to Crimean Tatars

- Noman Çelebicihan Battalion

- De-Tatarization of Crimea

- Aqmescit Friday mosque

- Crimean legends

- Tatarophobia

- Tatars

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Crimean Tatar population of Ukraine and Russia according to the 2001 Ukrainian and 2010 Russian censuses respectively, both held before 2014 annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation. A 2014 Crimean census, conducted by Russia after the annexation, reported 246,073 Crimean Tatars on the Russian-held territory[186][187][188]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The distribution of the population by nationality [ethnicity] and mother tongue". Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Big Russian Encyclopedia – Crimean Tatars". Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Recensamant Romania 2002". Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii (in Romanian). 2002. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity Archived 24 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "Bulgaria Population census 2001". Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Перепись 2009. (in Russian) Archived 1 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Национальный состав населения Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.rar)

- ^ "The Crimean Tatar National Movement and the American Diaspora". Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Novik, Aleksandr (2011). Культурное наследие народов Европы (in Russian). Наука. ISBN 978-5-02-038267-1.

- ^ Williams, Brian (2021). The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-49128-1.

The Turks and Crimean Tatars are both Turkic peoples and closely related by language, religion, and cultural tradition.

- ^ a b c Agdzhoyan 2018.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2001). "The Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. An Historical Reinterpretation". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 11 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1017/S1356186301000311. JSTOR 25188176. S2CID 162929705. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Агджоян А. Т., Схаляхо Р. А., Утевская О. М., Жабагин М. К., Тагирли Ш. Г., Дамба Л. Д., Атраментова Л. А., Балановский О. П. Генофонд крымских татар в сравнении с тюркоязычными народами Европы Archived 2020-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, 2015

- ^ Illarionov, A. (2014). "The ethnic composition of Crimea during three centuries" (in Russian). Moscow, R.F.: Institute of Economical Analysis. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- ^ Troynitski, N.A. (1905). "First General Census of Russian Empire's Population, 1897 (Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Под ред. Н.А.Тройницкого. т.II. Общий свод по Империи результатов разработки данных Первой Всеобщей переписи населения, произведенной 28 января 1897 года. С.-Петербург: типография "Общественная польза", 1899–1905, 89 томах (119 книг))" (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Dennis, Brad (3 July 2019). "Armenians and the Cleansing of Muslims 1878–1915: Influences from the Balkans". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 39 (3): 411–431. doi:10.1080/13602004.2019.1654186. ISSN 1360-2004. S2CID 202282745. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (1991). "'Punished Peoples' of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF). p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "UNPO: Crimean Tatars". unpo.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Verkhovna Rada recognized Crimean Tatars indigenous people of Ukraine (Рада визнала кримських татар корінним народом у складі України) Archived 28 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Mirror Weekly. 20 March 2014

- ^ Dahl, J. (2012). The Indigenous Space and Marginalized Peoples in the United Nations. Springer. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-1-137-28054-1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Vanguri, Star (2016). Rhetorics of Names and Naming. Routledge. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-317-43604-1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Uehling, Greta Lynn (2000). Having a Homeland: Recalling the Deportation, Exile, and Repatriation of Crimean Tatars. University of Michigan. pp. 420–424. ISBN 978-0-599-98653-4. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Yevstigneev, Yuri (2008). Россия: коренные народы и зарубежные диаспоры (краткий этно-исторический справочник) – lit. "Russia: indigenous peoples and foreign diasporas (a brief ethno-historical reference)" (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Litres. ISBN 9785457236653. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ a b Vozgrin, Valery "Historical fate of the Crimean Tatars" Archived 11 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sasse, Gwendolyn (2007). The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict. Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-932650-01-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (1999). A Homeland Lost: Migration, the Diaspora Experience and the Forging of Crimean Tatar National Identity. University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 541. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ In the 2014 census, many of those who indicated the nationality "Tatar" in the census were actually Crimean Tatars.

- ^ "World Atlas of Languages - Crimean Tatar".

- ^ "National Corpus of the Crimean Tatar Language | Фонд Східна Європа". East Europe Foundation. 21 December 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "The Crimean Tatar language belongs to the languages that are under serious threat". Представництво Президента України в Автономній Республіці Крим. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Tatar language | History, People, & Locations | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Sava, Işılay IŞIKTAŞ (21 September 2022). "KIRIM TATARCADA MOĞOLCA ALINTI KELİMELER". Karadeniz Araştırmaları (in Turkish). 19 (75): 933–951. doi:10.56694/karadearas.1173609. ISSN 2536-5126.

- ^ Kavitskaya, Darya (1 January 2009). Crimean Tatar. LINCOM publishers. p. 11. ISBN 978-3895866906.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams (2001) "The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation", ISBN 90-04-12122-6

- ^ National movements and national identity among the Crimean Tatars: (1905-1916). BRILL. 1996. ISBN 9789004105096.

- ^ Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1936). The Goths in the Crimea. Cambridge, MA. p. 259.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Crimean Tatars (КРИМСЬКІ ТАТАРИ) Archived 25 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

- ^ Dariusz Kolodziejczyk (2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th-18th Century), A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by an Annotated Edition of Relevant Documents. Vol. 47. BRILL. p. 352. ISBN 978-90-04-19190-7.

- ^ "Another New England — in Crimea". Big Think. 24 May 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz; Nomachi, Motoki; Gibson, Catherine (29 April 2016). The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-34839-5.

- ^ Geisenhainer, Katja; Lange, Katharina (2005). Bewegliche Horizonte: Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Bernhard Streck (in German). Leipziger Universitätsverlag. ISBN 978-3-86583-078-4.

- ^ "Mariupol Greeks". Great Russian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Greek Tatars. Urums, who are they? Moor did his job..."

- ^ "Шість століть разом. Сторінки історії забутого народу". crimea-is-ukraine.org (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Адас Якубаускас Литовські татари". www.ji.lviv.ua. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Польські і литовські татари у боротьбі за незалежний Крим в 1918 році". Іслам в Україні (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation". Iccrimea.org. 18 May 1944. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Khodarkovsky – Russia's Steppe Frontier p. 11

- ^ Williams, BG. The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Pgs 7–23. ISBN 90-04-12122-6

- ^ William Zebina Ripley (1899). The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (Lowell Institute Lectures). D. Appleton and Company. pp. 420–.

crimean tatar language.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 449–450, see page 450, (1) half way down & (2) final line.

(1) Meanwhile the Tatars had got a firm footing in the northern and central parts of the peninsula as early as the 13th century...&...(2)...and in the first years of the 20th century, the Tatars emigrated in large numbers to the Ottoman empire.

- ^ Green, Cate. "The medieval 'New England': a forgotten Anglo-Saxon colony on the north-eastern Black Sea coast". Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Another New England — in Crimea". Big Think. 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ István Vásáry (2005) Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Stearns(1979:39–40).

- ^ "CUMAN". Christusrex.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Stearns (1978). "Sources for the Krimgotische". p. 37. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Агджоян А. Т., Схаляхо Р. А., Утевская О. М., Жабагин М. К., Тагирли Ш. Г., Дамба Л. Д., Атраментова Л. А., Балановский О. П. Генофонд крымских татар в сравнении с тюркоязычными народами Европы Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 2015

- ^ "Как мы изучали генофонд крымских татар | Генофонд РФ" (in Russian). xn--c1acc6aafa1c.xn--p1ai. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Стендовый доклад Аджогян" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn. 2001. "The Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. An Historical Reinterpretation". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 11 (3). Cambridge University Press: 329–48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25188176 Archived 13 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 46, 54, 66-67.

- ^ a b Agdzhoyan, Anastasiya; et al. (2014). "THE GENE POOL OF INDIGENOUS CRIMEAN POPULATIONS: MEDITERRANEAN MEETS EURASIAN STEPPE". Moscow University Anthropology Bulletin (Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Seria XXIII. Antropologia) (4). Moscow: 112.

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 46, 70.

- ^ a b c d e Следы древних миграций в генофонде крымских и казанских татар: анализ полиморфизма y-хромосомы = Traces of ancient migrations in the gene pool of Crimean and Kazan Tatars: analysis of y-chromosome polymorphism Archived 2018-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Агджоян А. Т., Утевкая О. М. и др. — Вестник УТГС 2013.

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 97: "Thus, medieval migrations from Asia Minor could have strengthened the "marine" layer of the Crimean gene pool, but its main source was still the ancient populations from the city-states of the Eastern Mediterranean. Indirect confirmation of this hypothesis can be found in the analysis of the Crimean Tatar gene pool according to the Human Origins genome-wide panel (Figure 17, Section 3.3) and the projection of the position of the gene pool of mountain and southern coastal Crimean Tatars on the principal component graph for the same data set, published in the work [Mathieson et al., 2017] using data on ancient DNA of the Balkans and Asia Minor from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age".

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 6, 15 etc..

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 92: "the gene pools of all the populations studied are very distant from both the Mongols and other populations of Central Asia"

- ^ Агджоян А. Т., Схаляхо Р. А., Утевская О. М., Жабагин М. К., Тагирли Ш. Г., Дамба Л. Д., Атраментова Л. А., Балановский О. П. Генофонд крымских татар в сравнении с тюркоязычными народами Европы Archived 2020-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, 2015

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 64: "All six studied Crimean populations, according to the analysis of both haploid and whole-genome autosomal markers, are genetically very distant from their closest geographical neighbors – Ukrainians and Russians: significantly farther than from the populations of the Mediterranean or the Caucasus. This result indicates the absence of a significant genetic contribution of the Slavic population to the gene pool of the studied Crimean populations".

- ^ Agdzhoyan.1, Anastasia. "Генофонд коренных народов Крыма по маркерам Y-хромосомы, мтДНК и полногеномных панелей аутосомных SNP" (PDF). Институт общей генетики им. Н.И. Вавилова Российской академии наук и лаборатория популяционной генетики человека Федерального государственного бюджетное научное учреждение «Медико-генетический научный центр» (in Russian): 20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wells, RS; Yuldasheva, N; Ruzibakiev, R. et al The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity // Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 53.

- ^ Comas, D., Plaza, S., Wells, R. et al. Admixture, migrations, and dispersals in Central Asia: evidence from maternal DNA lineages. Eur J Hum Genet 12, 495–504 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201160

Crimean Tatars were excluded from the admixture analysis since their geographic position corresponds more to Europe rather than Central Asia, and their mtDNA pool is completely of West Eurasian origin.

- ^ В. С. ПАНКРАТОВ, Е. И. КУШНЕРЕВИЧ, член-корреспондент О. Г. ДАВЫДЕНКО (2014). ПОЛИМОРФИЗМ МАРКЕРОВ Y-ХРОМОСОМЫ В ПОПУЛЯЦИИ БЕЛОРУССКИХ ТАТАР (in Russian). Минск: Национальная академия наук Беларуси. с. 95.

- ^ Agdzhoyan 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Мухамедьяров Ш. Ф. Введение в этническую историю Крыма. // Тюркские народы Крыма: Караимы. Крымские татары. Крымчаки. — Moscow: Наука. 2003.

- ^ Хайруддинов М. А. К вопросу об этногенезе крымских татар/М. А. Хайруддинов // Ученые записки Крымского государственного индустриально-педагогического института. Выпуск 2. -Симферополь, 2001.

- ^ Sevortyan E. V. Crimean Tatar language. // Languages of the peoples of the USSR. — t. 2 (Turkic languages). — N., 1966. — Pp. 234–259.

- ^ "Baskakov – on the classification of Turkic languages". www. philology. ru. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Essays on the history and culture of the Crimean Tatars. / Under. edited by E. Chubarova.Simferopol, Crimecity, 2005.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams (2015). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford University Press. p. xi–xii. ISBN 9780190494704. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Gertsen, Mogarychev Крепость драгоценностей. Кырк-Ор. Чуфут-кале. Archived 27 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, 1993, pages 58—64. — ISBN 5-7780-0216-5.

- ^ a b c d Brian L. Davies (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe. pp. 15–26. Routledge.

- ^ Крымское ханство: вассалитет или независимость? // Османский мир и османистика. Сборник статей к 100-летию со дня рождения А.С. Тверитиновой (1910–1973) Archived 14 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine М., 2010. С. 288–298

- ^ Williams, BG. The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Pg 12. ISBN 90-04-12122-6

- ^ a b c d Rayfield, Donald, 2014: "Dormant claims", Times Literary Supplement, 9 May 2014 p 15

- ^ a b c Gayvoronsky, 2007

- ^ Vosgrin, 1992. ISBN 5-244-00641-X.

- ^ Halil İnalcik, 1942 [page needed]

- ^ Great Russian Encyclopedia: Верховная власть принадлежала хану – представителю династии Гиреев, который являлся вассалом тур. султана (официально закреплено в 1580-х гг., когда имя султана стало произноситься перед именем хана во время пятничной молитвы, что в мусульм. мире служило признаком вассалитета) Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kochegarov Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (2008), p. 230

- ^ J. Tyszkiewicz. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejow XIII-XVIII w. Warszawa, 1989. p. 167

- ^ Davies (2007), p. 187; Torke (1997), p. 110

- ^ There is a popular thesis in the Russian-Soviet propaganda about the Crimean Tatars betrayal of Khmelnytsky. However, the words of the vizier of the Crimean khanate Sefer Ğazı show just the opposite. He said: «The Zaporozhian Cossacks spent 800 years in servitude with the Polish kings, then seven years with us, and we, taking them together and hoping that they would be righteous and standing in service, defended them, fought for them with Poland and Lithuania, shed a lot of innocent blood, and did not allow them to be harmed. Back then there were only 8,000 Cossacks, and we Tatars made 20,000 of them. The Cossacks liked it, when we covered them and always came to their aid, then Khmelnytsky kissed me, Sefergazy-Aga, in the legs and wanted to be with us in submission forever. Now the Cossacks have misappropriated us, betrayed us, forgotten our goodness, gone to the Tsar of Moscow. You, members, know that it is traitors and rebels who will betray the Tsar just as they betrayed us and the Poles. Mehmed Giray the Tsar is unable to do anything but to walk on them and destroy them. I do not think any of the Crimeans and Nogais will have a claw on the fingers of their hands, I don't think their eyes will be covered with ground – then only the treachery and the Cossack faith will be avenged.» (source of the quote Archived 7 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Ahmad III, H. Bowen, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H. A. R. Gibb, J. H. Kramers, E. Levi-Provencal and J. Shacht, (E. J.Brill, 1986), 269.

- ^ He was claiming: "Such a strong and merciless enemy as Moscow, falling on its feet, fell into our hands. This is such a convenient case when, if we wish so, we can capture Russia from one side to the other, since I know for sure that the whole the strength of the Russian army is this army. Our task now is to pat the Russian army so that it cannot move anywhere from this place, and we will get to Moscow and bring the matter to the point that the Russian Tsar would be appointed by our padishah" (Halim Giray, 1822)

- ^ Halim Giray Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 1822 (in Russian)

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II. ABC-CLIO. p. 732

- ^ a b c Great Russian Encyclopedia: Крымское ханство Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine — A. V. Vinogradov, S. F. Faizov

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). "Ukraine: A History". University of Toronto Press. pp. 105–106.

- ^ Paul Robert, Magocsi (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples, Second Edition. University of Toronto Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-1442698796. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "The Crimean Tatars and the Ottomans". Hürriyet Daily News. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ a b Mikhail Kizilov (2007). "Slave Trade in the Early Modern Crimea From the Perspective of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources". Journal of Early Modern History. 11 (1). Oxford University: 2–7. doi:10.1163/157006507780385125. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Yermolenko, Galina I. (2010). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 111. ISBN 978-1409403746. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Eizo Matsuki, Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University.

- ^ Fisher, Alan (1981). "The Ottoman Crimea in the Sixteenth Century". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 5 (2): 135–170. JSTOR 41035903.

- ^ a b c d Alan W. Fisher, The Russian Annexation of the Crimea 1772–1783, Cambridge University Press, p. 26.

- ^ "Украине не стоит придумывать мифы о Крыме, ведь он украинский по праву – историк" (in Russian). Крим.Реалії. 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Bykova 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Serhiychuk 2008, p. 216.

- ^ Great Russian Encyclopedia Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine: Crimean Khanate

- ^ Религия Караимов Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Глаголев В. С., page 88

- ^ Darjusz Kołodziejczyk, as reported by Mikhail Kizilov (2007). "Slaves, Money Lenders, and Prisoner Guards:The Jews and the Trade in Slaves and Captivesin the Crimean Khanate". The Journal of Jewish Studies: 2. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams (2013). "The Sultan's Raiders: The Military Role of the Crimean Tatars in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013.

- ^ The historical fate of the Crimean Tatars Archived 20 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine — Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Valery Vozgrin, 1992, Moscow (in Russian)

- ^ "The economy of the Crimean Khanate". Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ RFEL:Сергей Громенко против «лысенковщины» в истории Крыма Archived 31 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "Как переписывали историю Крыма (How the Crimean history was rewritten)". Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Serhiy Hromenko «Все было не так»: зачем Россия переписывает историю Крыма Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gulnara Bekirova: Крымскотатарская проблема в СССР: 1944–1991 Archived 31 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gulnara Bekirova Crimea and the Crimean Tatars in XIX—XXth centuries Archived 31 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 2005, page 95

- ^ "Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to the Ottoman Empire" Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, by Bryan Glynn Williams, Cahiers du Monde russe, 41/1, 2000, pp. 79–108.

- ^ Хаяли Л. И. — Провозглашение Крымской народной республики (декабрь 1917 года) Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Maria Drohobycky, Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects, Rowman & Littlefield, 1995, p.91, ISBN 0847680673

- ^ a b c Minahan, James (2000). Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 189. ISBN 9780313309847. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Kinstler, Linda (2 March 2014). "The Crimean Tatars: A Primer". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Aurélie Campana, Sürgün: "The Crimean Tatars’ deportation and exile, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence" Archived 10 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 16 June 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2012, ISSN 1961-9898

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 483. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ^ The Muzhik & the Commissar, Time, 30 November 1953

- ^ Fisher, Alan W. (2014). Crimean Tatars. Hoover Press. pp. 250–252. ISBN 9780817966638. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b Williams, Brian Glyn (2015). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780190494711. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Uehling, Greta (26 November 2004). Beyond Memory: The Crimean Tatars' Deportation and Return. Springer. p. 100. ISBN 9781403981271. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b Allworth, Edward (1998). The Tatars of Crimea: Return to the Homeland : Studies and Documents. Duke University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 9780822319948.

- ^ Stronski, Paul (2010). Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930–1966. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 9780822973898. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b Naimark, Norman (2002). Fires of Hatred. Harvard University Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 9780674975828. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Хаяли Р. И. Политико-правовое урегулирование крымскотатарской проблемы в СССР (1956—1991 гг.) Archived 20 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine // Ленинградский юридический журнал. 2016 № 3. стр. 28-38

- ^ Buckley, Cynthia J.; Ruble, Blair A.; Hofmann, Erin Trouth (2008). Migration, Homeland, and Belonging in Eurasia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780801890758. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2015). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford University Press. pp. 108, 136. ISBN 9780190494704. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Buttino, Marco (1993). In a Collapsing Empire: Underdevelopment, Ethnic Conflicts and Nationalisms in the Soviet Union, p.68 Archived 31 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 88-07-99048-2

- ^ United States Congress Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (1977). Basket Three, Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Religious liberty and minority rights in the Soviet Union. Helsinki compliance in Eastern Europe. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 261. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Report. The Group. 1970. pp. 14–20.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2001). The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. BRILL. ISBN 9789004121225. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b Allworth, Edward (1988). Tatars of the Crimea: Their Struggle for Survival : Original Studies from North America, Unofficial and Official Documents from Czarist and Soviet Sources. Duke University Press. pp. 55, 167–169. ISBN 9780822307587. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Gromenko, Sergey (2016). Наш Крим: неросійські історії українського півострова (in Ukrainian). Український інститут національної пам’яті. pp. 283–286. ISBN 9786176841531. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Yakupova, Venera (2009). Крымские татары, или Привет от Сталина! (PDF). Kazan: Часы истории. pp. 28–30, 47–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Russia. Chalidze Publication. 1983. pp. 121–122.

- ^ Smith, Graham (1996). The nationalities question in the post-Soviet states. Longman. ISBN 9780582218086.

- ^ Fouse, Gary C. (2000). The Languages of the Former Soviet Republics: Their History and Development. University Press of America. p. 340. ISBN 9780761816072. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Mastny, Vojtech (2019). Soviet/east European Survey, 1987-1988: Selected Research And Analysis From Radio Free Europe/radio Liberty. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 9781000312751. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Report Submitted to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives and Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate by the Department of State in Accordance with Sections 116(d) and 502B(b) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as Amended. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1989. p. 1230. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Vyatkin, Anatoly (1997). Крымские татары: проблемы репатриации (in Russian). Ин-т востоковедения РАН. p. 32. ISBN 9785892820318. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Bekirova, Gulnara (1 April 2016). "Юрий Османов". Крым.Реалии (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Skutsch, Carl (2005). Encyclopedia of the world's minorities. Routledge. p. 1190. ISBN 9781579584702. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Arbatov, Aleksey; Lynn-Jones, Sean; Motley, Karen (1997). Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780262510936. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Gabrielyan, Oleg (1998). Крымские репатрианты: депортация, возвращение и обустройство (in Russian). Amena. p. 321.

- ^ a b Kuzio, Taras (24 June 2009). "Crimean Tatars Divide Ukraine and Russia". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b Humeniuk, Natalia. "Самоповернення в Крим" [Self-return in Crimea]. Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Лидер Меджлиса уверен, что самозахват земли в Крыму не остановить" [Mejlis leader certain squatting of Crimean lands cannot be stopped]. Segodnya (in Russian). 4 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "U.N. human rights team aims for quick access to Crimea – official". Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "UNPO: Crimean Tatars: Turkey Officially Condemns Persecution by Russia". unpo.org. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Russia's War Against Crimean Tatars". 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Temirgaliyev, Rustam (19 March 2014). "Crimean Deputy Prime Minister". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ Trukhan, Vassyl. "Crimea's Tatars flee for Ukraine far west". Yahoo. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Baczynska, Gabriela (29 March 2014). "Crimean Tatars' want autonomy after Russia's seizure of peninsula". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "World". Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.