Badajoz

Badajoz

Badajos | |

|---|---|

Location of Badajoz | |

| Coordinates: 38°52′49″N 6°58′31″W / 38.88028°N 6.97528°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous Community | Extremadura |

| Province | Badajoz |

| Comarca | Tierra de Badajoz |

| Founded | c. 875 |

| Founded by | Ibn Marwan (over a previous Visigothic settlement) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ignacio Gragera (PP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,470 km2 (570 sq mi) |

| Elevation (AMSL) | 185 m (607 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 150,530 |

| • Rank | 302 |

| • Density | 100/km2 (270/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST (GMT +2)) |

| Postal code | 70862 |

| Area code | +34 (Spain) + 924 (Badajoz) |

| Website | www |

Badajoz[a] is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The population in 2011 was 151,565.

Badajoz was conquered by the Moors in the 8th century and re-founded as Baṭalyaws, and later in the 11th century the city became the seat of a separate Moorish kingdom, the Taifa of Badajoz. After the Reconquista, the area was disputed between Spain and Portugal for several centuries with alternating control resulting in several wars including the Spanish War of Succession (1705), the Peninsular War (1808–1811), the Storming of Badajoz (1812), and the Spanish Civil War (1936). Spanish history is largely reflected in the town.

Badajoz is the see of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mérida-Badajoz. Prior to the merger of the Diocese of Mérida and the Diocese of Badajoz, Badajoz was the see of the Diocese of Badajoz from the bishopric's inception in 1255. The city has a degree of eminence, crowned as it is by the ruins of the Moorish castle Alcazaba of Badajoz and overlooking the Guadiana river, which flows between the castle-hill and the powerfully armed fort of San Cristobal. The architecture of Badajoz is indicative of its tempestuous history; even the Badajoz Cathedral, built in 1238, resembles a fortress, with its massive walls. It is served by Badajoz Railway Station and Badajoz Airport.

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]Archaeological finds unearthed in the Badajoz area have been dated to the Bronze Age. Megalithic tombs are dated as far back as 4000 BC,[2] while many of the steles found are from the Late Bronze Age.[3] Other finds include weapons such as axes and swords, everyday items of pottery and utensils, and various items of jewellery such as bracelets. Archaeological excavations have revealed remnants from the Lower Paleolithic period. Artifacts have also been found at the Roman town of Colonia Civitas Pacensis in the Badajoz area, although a significant number of larger artifacts were found in Mérida.[4][5]

With the invasion of the Romans, which started in 218 BC during the Second Punic War, Badajoz and Extremadura became part of the administrative district called Hispania Ulterior (Farther Spain), which was later divided by Emperor Augustus into Hispania Ulterior Baetica and Hispania Ulterior Lusitania; Badajoz became part of Lusitania.[6] Though the settlement is not mentioned in Roman history, Roman villas such as the La Cocosa Villa have been discovered in the area, while Visigothic constructions have also been found in the vicinity.[7]

Founding to Middle Ages

[edit]

Badajoz attained importance during the reign of Moorish rulers such as the Umayyad caliphs of Córdoba, and the Almoravids and Almohads of North Africa. From the 8th century, the Umayyad dynasty controlled the region until the early 11th century.[8] The official foundation of Badajoz was laid by the Muladi nobleman Ibn Marwan, around 875,[9] after he had been expelled from Mérida.[10] Under Ibn Marwan, the city was the seat of an effective autonomous rebel state which was quenched only in the 10th century. In 1021 (or possibly 1031[11]), it became the capital of a small Muslim kingdom, the Taifa of Badajoz;[5] with some 25,000 inhabitants.[8] Badajoz was known as Baṭalyaws (Arabic: بَطَلْيَوْس) during Muslim rule, from which its present name gradually evolved. The invasion of Badajoz by Christian rulers in 1086 under Alfonso VI of León, overturned the rule of the Moors. In addition to an invasion by the Almoravids of Morocco in 1067, Badajoz was later invaded by the Almohads in 1147.[12]

Badajoz was captured by Alfonso IX of León on 19 March 1230.[13] Shortly after its conquest, in the time of Alfonso X the Wise of Castile, a bishopric see was established and work was initiated on the Cathedral of San Juan Bautista. In 1336, during the reign of Alfonso XI of Castile, the troops of King Afonso IV of Portugal besieged the city.[14] However, soon afterwards,[14] the Castilian-Leonese troops, which included Pedro Ponce de León the Elder and Juan Alonso Pérez de Guzmán y Coronel, second lord of Sanlúcar de Barrameda and son of Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, defeated the troops of Afonso IV in the Battle of Villanueva de Barcarrota. Their victory forced the king of Portugal to desert the city and it fell into neglect.

In medieval times, the Sánchez de Badajoz family dominated the area as the lords of Barcarrota, near Badajoz, acquiring the property in 1369 when it was granted to Fernán Sánchez de Badajoz by Enrique II.[15] They temporarily lost Barcarrota to the Portuguese but soon regained control. Fernán Sánchez's grandson of the same name, son of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz, was both lord of Barcarrota and Mayor of Badajoz in 1434.[15] Garci Sánchez de Badajoz, probably his son, was a notable writer, and one of his descendants, Diego Sánchez de Badajoz, was also a notable playwright; his Recopilación en metro was published posthumously in 1554.[16]

From the 11th century-1492, a Jewish community existed in Badajoz.[17]

The first hospital was founded in the town by Bishop Fray Pedro de Silva in 1485.[18] Those affected by the plague epidemic were treated here in 1506. During the 16th century the city experienced a cultural renaissance thanks to personalities such as the painter Luis de Morales, the composer Juan Vázquez, the humanist Rodrigo Dosma, the poet Joaquin Romero de Cepeda, the playwright Diego Sánchez de Badajoz, the Dominican mystic Fray Luis de Granada and architect Gaspar Méndez. In 1524, a board meeting between representatives of Spain and Portugal took place in the Old Town Hall in the city to clarify the status of their territorial arrangements, attended by Hernando Colón, Juan Vespucio, Sebastián Caboto, Juan Sebastián Elcano, Diego Ribeiro and Esteban Gómez.[19]

With reason to assert their rights to the Portuguese Crown, Philip II of Spain briefly moved his court to Badajoz in August 1580. Queen Anne of Austria died in the city two months later, and on 5 December 1580, Philip moved out of the city.[20][21] From 1580 until 1640, as a result of the absence of war, the city flourished once again. According to the historian Vicente Navarro del Castillo, some 428 residents of Badajoz contributed to the Spanish conquest of the Americas, including conquistadors Diego de Valadés,[22] Pedro de Alvarado, Luis de Moscoso, and Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas (father of Inca Garcilaso). In 1640, the city was attacked during the Portuguese Restoration War.[23]

1660–1811

[edit]

The battle for control of the town and its fortress continued with attacks by the Portuguese in 1660. In 1705, during the Spanish War of Succession, Badajoz was controlled by the Allies following the death of the heirless King Charles II. It was taken by Spain, prompting Philip V, grandson of Louis XIV of France, to take over the reins of Spain itself.[5][11] In 1715 Portugal signed a peace agreement with Spain and surrendered its claims to Badajoz in lieu of Spain's cession of Sacramento territory in the La Plata area in South America.[24] The Peace Treaty of Badajoz was signed between Spain and Portugal on 6 June 1801.[25] The Portuguese, feeling that an attack by French troops stationed in Ciudad Rodrigo was imminent, agreed to cede Olivenza to Spain and declared that it would close its ports to British ships.[25] This agreement was revoked in 1807 as its terms were breached when the Treaty of Fontainbleau was signed between Spain and France on 27 October 1807.[25]

During the Peninsular War, Badajoz was unsuccessfully attacked by the French in 1808 and 1809. However, on 10 March 1811, the Spanish commander, José Imaz, was bribed into surrendering to a French force under Marshal Soult.[11] A British and Portuguese army, commanded by Marshal Beresford, endeavoured to retake it and on 16 May 1811 defeated a relieving force at Albuera, but the siege was abandoned the following month.[11]

The Storming of Badajoz (1812)

[edit]

In 1812, Arthur Wellesley, Earl of Wellington (and future duke), again attempted to take Badajoz, which had a French garrison of about 5,000 men.[26] Siege operations commenced on 16 March; by early April, there were three practicable breaches[b] in the walls. These were assaulted by two British divisions on 6 April, reputed to be "Wellington's bloodiest siege", with a loss of some 5,000 British soldiers out of 15,000.[28] After a five-hour onslaught the storming of the breaches failed.[29] The French also lost some 1,200 of their 5,000 soldiers in the battle.[28] Despite the failure at the breaches, the castle and another section of undamaged wall had been attacked and the town was successfully taken by the British. After the capture of the city, the victorious troops (after getting drunk on stocks of captured alcohol) sacked the city, killing and raping numerous civilians. In the view of British historian Ronald Fraser, this was the worst night of the Peninsular War.[27] It took three days before the men were brought back into order. When order was restored some 200–300 civilians had likely been killed or injured.[30] Wellington wrote to Lord Liverpool, "The capture of Badajos affords as strong an instance of the gallantry of our troops as has ever been displayed, but I anxiously hope that I shall never again be the instrument of putting them to such a test as that to which they were put last night."[31]

Pedro Caro, 3rd Marquis of la Romana, died at Badajoz on 23 January 1811 in a fit of apoplexy, seized at the moment when he was leaving his house to concert a plan of military operations with Lord Wellington. In the Siege of Badajoz, a detachment of the 45th Regiment of Foot (later amalgamated with the 95th to form the Sherwood Foresters Regiment) succeeded in getting into the castle first and the red coatee of Lt. James MacPherson of the 45th regiment was hoisted in place of the French flag to indicate the fall of the castle. This feat is commemorated on 6 April each year, when red jackets are flown on regimental flag staffs and at Nottingham Castle. Volume 23 of the Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art, published in 1833, described Badajoz as "one of the richest and most beautiful towns in the south of Spain, whose inhabitants had witnessed its siege in silent terror for one and twenty days, and who had been shocked by the frightful massacre."[32] On 5 August 1883 there was an attempted mutiny by elements of the Spanish Armed Forces when a climate of confusion and chaos prevailed.[33]

Spanish Civil War

[edit]The Spanish Civil War in Badajoz in the 1930s was a gruesome affair.[12] During the war, Badajoz was taken by the Nationalists in the Battle of Badajoz. Infamously, several thousand of the town's inhabitants, both men and women, were taken to the town's bullring after the battle and after machine guns were set up on the barriers around the ring, an indiscriminate slaughter began. On 14 August 1936, hundreds of Republicans were shot at the Plaza de Toros.[34] In the course of the night, another 1,200 were brought in. Overall it is estimated that over 4,000 people were murdered by the Nationalists after the battle.[35] Even those who tried to cross the Portuguese border were captured and sent back to Badajoz.[12] The troops who committed the killings at Badajoz were under the command of general Juan Yagüe, who, after the civil war, was appointed Minister of Aviation by Franco. For the actions of his troops at Badajoz, Yagüe was popularly known as the "Butcher of Badajoz".[36]

Modern history

[edit]After the war, the town continued to grow, although since 1960 it has suffered significant migrations to other Spanish regions and other European countries. During the following decades, the predominant economic activity of the city increasingly fell within the tertiary sector, and today Badajoz is a major commercial centre in southwestern Spain and an important bridge between Spain and Portugal for trade and cultural relations. On 6 November 1997, a heavy flood devastated several neighbourhoods of the city, causing the deaths of 21 people and devastating the property of hundreds.[37] The catastrophe was caused by the Atlantic extratropical trough crossing the Iberian Peninsula and inundating the Rivilla and Calamon brooks, which are usually dry.[37] The neighbourhood of Cerro de Reyes, near the confluence of both streams, received the brunt of the damage caused by the flood.[37]

Geography

[edit]

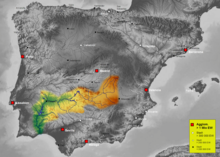

Badajoz is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula on the bank of the Guadiana River on the border with Portugal.[38] It is the capital city of the province of the same name.[5] It is 61 kilometres (38 mi) from Mérida, 89 kilometres (55 mi) from Cáceres, 217 kilometres (135 mi) from Seville, 227 kilometres (141 mi) east of Lisbon, and 406 kilometres (252 mi) from Madrid. The newer part of the city is on the left bank of the river, with several industrial estates and the university hospital.

In geological terms, Badajoz is located in the South Submeseta.[39] It was founded on the banks of the Guadiana River on a Paleozoic limestone hill, carved by the river. On this hill is the Alcazaba, one of the main sights of the city. The municipality of Badajoz contains soils derived from tertiary deposits, dating to the Paleozoic era. Its average altitude is 184 metres (604 ft) above sea level. The highest points are located in the Cerro del Viento (219 metres (719 ft)), at Fuerte San Cristóbal (218 metres (715 ft)) and Cerro de la Muela (205 metres (673 ft)). The lowest point is the Guadiana River (168 metres (551 ft)).

Climate

[edit]Badajoz has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) being very similar to the climates found between the microclimates of the coast and of the central valley of California (e.g. Stockton[40]), with mild winters but with more common temperatures below zero and hot summers being sometimes a year at 40 °C or more.[41] At the same time the precipitation is at a threshold close to a semi-arid climate. The climate of Badajoz has drastic changes between the summer and winter as seen in the chart below. Altitude of the measuring station is 203 metres (666 ft). The average annual temperature is 17.1 °C (62.8 °F). The average high temperature in July is 34.8 °C (94.6 °F) whereas the coldest average low temperatures is 3.3 °C (37.9 °F) in January. Average annual rainfall is 447 millimetres (17.6 in), with December recording the maximum of 69 millimetres (2.7 in) and July is the driest month with rainfall of 0.5 millimetres (0.020 in).[42] Humidity level is at an annual average level of 64%. The city receives an average 2,860 hours of sunshine a year.[43]

| Climate data for Badajoz (1991–2020), extremes (1920–) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.6 (101.5) |

43.4 (110.1) |

45.4 (113.7) |

44.8 (112.6) |

43.7 (110.7) |

35.8 (96.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

45.4 (113.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46.7 (1.84) |

39.0 (1.54) |

41.3 (1.63) |

42.6 (1.68) |

38.0 (1.50) |

12.5 (0.49) |

3.3 (0.13) |

4.6 (0.18) |

23.4 (0.92) |

63.8 (2.51) |

59.9 (2.36) |

60.6 (2.39) |

435.7 (17.15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.6 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 58.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143 | 175 | 227 | 252 | 303 | 348 | 387 | 352 | 272 | 210 | 156 | 122 | 2,947 |

| Source: Météo Climat[44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Badajoz (1981–2010), extremes (1920–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.2 (91.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

43.4 (110.1) |

45.3 (113.5) |

44.8 (112.6) |

43.7 (110.7) |

35.4 (95.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

45.3 (113.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50 (2.0) |

42 (1.7) |

30 (1.2) |

49 (1.9) |

36 (1.4) |

14 (0.6) |

4 (0.2) |

5 (0.2) |

24 (0.9) |

61 (2.4) |

65 (2.6) |

69 (2.7) |

447 (17.6) |

| Average precipitation days | 6.6 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 59.2 |

| Average snowy days | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 74 | 65 | 64 | 58 | 52 | 48 | 49 | 56 | 68 | 76 | 82 | 64 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 146 | 163 | 226 | 244 | 292 | 335 | 376 | 342 | 260 | 206 | 155 | 114 | 2,860 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[43][45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]In 2010, Badajoz had 150,376 inhabitants. According to the 2010 census, Badajoz had 73,074 men and 77,312 women, representing a percentage of 48.6% and a 51.4% respectively.[46] Compared to the statistics for the Extremadura region (49.7% and 50.3%), Badajoz city had a greater relative presence of women.

Although the city is the most populated of Extremadura, it has a relatively low population density (102.30 inhabitants/km2), due to the extension of its municipality, one of the largest in Spain, with an area of 1,470 km2. In addition to the metropolitan centre the population includes districts, neighborhoods and towns with small populations, the most populous of which is Guadiana, which had 2,524 people in 2012, but gained independence on 17 February 2012.[47]

- Source: INE

Note: The increase shown in 2001 was reduced because of the independence of the municipalities of Valdelacalzada and Pueblonuevo del Guadiana in 1993.[48]

Administration

[edit]Badajoz was the birthplace of the statesman Manuel de Godoy, the duke of Alcudia (1767–1851). Many of the provincial administration buildings are located in Badajoz, as well as the government buildings of the municipal administration. Politically, Badajoz belongs to the Spanish Congress Electoral District of Badajoz, which is the largest electoral district about of 52 districts in the Spanish Congress of Deputies in terms of geographical area and includes a significant part of the Extremadura region. The electoral district was first contested in modern times in the 1977 General Election.[49] At the time of the 2011 election, Badajoz had six deputies representing the district in congress, four from the People's Party-United Extremadura party (PP-EU), and two from the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).[50]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

|

|

|

|

Districts

[edit]| Name | Type | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Alcazaba | District | 254 |

| Alvarado | District | 389 |

| Balboa | District | 532 |

| Gévora | District | 2308 |

| Guadiana del Caudillo | Gained independence on 17 February 2012[51] | 2543 |

| Novelda del Guadiana | District | 909 |

| Sagrajas | District | 631 |

| Valdebótoa | District | 1.294 |

| Villafranco del Guadiana | District | 1.544 |

| TOTAL PEDANÍAS | 7861 |

Economy

[edit]Historically, frequent wars ravaged Badajoz's economy and people were poor. Agricultural land was not fertile with no industry of any major importance in its territory. However, the historic monuments in the town and also in Mérida were major attractions to visitors, leading to the growth of tourism, and in recent years there has been some industrial development.[12]

Badajoz primarily is now a commercial city, ranked 25th place in economic importance in Spain according to Spain's Economic Yearbook for 2007, published by Servicio de Estudios de La Caixa. Because of its location, the city shares a considerable transit trade with Portugal. The service sector is dominant in the city. The main shopping street is Menacho, where most national and international chains are located. The Centro Comercial Abierto Menacho is the largest outdoor shopping centre in Extremadura which has had several hundred thousand euros invested into it, and it is visited by thousands of Portuguese a year.[52] Notable industries include manufacturing of linen, woollen and leather goods, hats, pottery, and soap.[53] Trade thrives on customers from the province and Portugal. Because of the importance of such trading relations with the neighboring country, in 2006, a new trade fair venue, Institución Ferial de Badajoz (IFEBA) was established in the suburbs near the bank of the Caia River. An economic and cultural centre, it has a wide range of markets from fish and various food stalls to health shops,"[54] The Old Town area has been affected by this trade fair but is slowly recovering, with the opening of new stores.[55]

The city's industrial land on the western side of the river is concentrated almost entirely in a large industrial estate, El Nevero, located next to the A-5 (one of the six radial roads in Spain with numbers A-1-A-6), which is continually expanding, with a diversity of companies operating there. There are also other industrial estates in the suburbs and small businesses in neighborhoods like San Roque. In summer 2007, the project to build the new 38 million euro headquarters of the Caja de Badajoz was made public,[56] which began to be built in October 2008 and is currently in use. The Torre Caja Badajoz is a financial centre that has a building height of 88 metres (289 ft) with 17 floors, now the tallest building in Extremadura.[57] The city also has an airport, located 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) from the town centre, expanded in 2009 and a conference centre.[58]

Notable landmarks

[edit]The city is studded with Moorish and medieval architecture, although its remnants of Roman and Visigothic architecture are not as prominent as in nearby Mérida.[5] The Alcazaba fortress is the most notable structure in the city which attests to the Moorish culture in Badajoz. It was the only important fort on the southern Portuguese frontier during the 17th and 18th centuries and controlled the routes of southern Portugal and Andalusia and was a staging point for invasions against Portugal.[24] It was occupied by the dukes of La Roca during the Christian period. It presently serves as the Archeological Museum of Badajoz.[8] Many of Badajoz's historical monuments which were in ruins have been refurbished. Its restaurants, pubs and nightlife are a major attraction for the Portuguese across the border.[59] The 13th-century Badajoz Cathedral (converted from a mosque in 1238) is in the old city and its architecture is indicative of the tempestuous history of Badajoz, resembling a fortress, with its massive walls.[11] Three of the cathedral's windows are unique – one is in Gothic style, the second is Renaissance style and the third is in Platersque style. [60]

Municipal buildings

[edit]

Palacio de Congresos de Badajoz, the congressional palace, is the work of the architects José Selgas and Lucia Cano. Palacio Municipal houses the City Hall. The remains of the original City Hall building are in ruins. The current building dates to 1852, and the clock was added in 1889.[61] In 1937, the municipal architect, Rodolfo Martinez, renovated the building, with particular emphasis on stylistic uniformity, expanding its towers and changing its decorative elements. It features a balustrade, a central balcony and columns.

Badajoz has several municipal libraries serving the city and wider province, including the Biblioteca Pública Municipal A. Dominguez, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Bda. de Llera, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Cerro de Reyes, Biblioteca Pública Municipal Pardaleras, and the Biblioteca Pública Municipal San Roque.

Historical sites

[edit]

Alcazaba

[edit]The Alcazaba, a Moorish citadel built in the 9th century by Ibn Marwan, was fortified by the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf in 1169, although there are traces of earlier work dating back to 913 and 1030. The Alcazaba served as the primary residences for the rulers of the Taifa of Badajoz in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Almohad rulers were expelled in the 13th century at the hands of Alfonso IX of León.[62] The Torre de Espantaperros has a height of 30 metres (98 ft) and is built of mud and mortar. It has an octagonal plan with a quadrangular structure that once provided scenic views of the countryside. The name is attributed to the sharp ringing of a bell that was one installed in the tower. The building attached to it, built in the 16th century called La Galera, once served as city hall, then a prison and finally it is now the Archaeological Museum. A well-tended garden surrounded this monument where archeological finds from the Visigothic, Roman, and other periods were found.[63][12][64]

Vauban fort

[edit]The Vauban military fort was built in the 17th century during the war between Spain and Portugal that lasted from 1640 to 1668 as a defense measure to counter-attack forces entering the city from the northwest and southeast. It is made of stone, brick and lime concrete. It has eight bastions built on the northern part of the fort as the Guadiana and Rivilla rivers on the south provided the defense. The bastions are named as the San Pedro, La Trinidad, the Santa María, the San Roque, the San Juan, the Santiago, the San José and the San Vicente.[65]

La Giralda

[edit]

La Giralda, located near Plaza de la Soledad, is a replica of the Giralda in Sevilla. The structure was completed in 1930 by a local businessman for commercial intent.[66] Built in the neo-Arab Andalusian regionalist style, it is decorated with ceramic tiles and metal work and has the symbol of Mercury embossed on it as symbol of commerce.[67] In 1978, Telefónica acquired the building and refurbished it, established operating offices. In 1998, Telefónica vacated the structure, and four years later, offered the structure to potential buyers for €4.2 million. No buyer was uncovered, and Telefónica announced plans to reestablish local offices in the Giralda but later abandoned it. Various proposals for the local government to acquire the building have been made, including plans for appropriating an expansion of the Museum of Fine Arts, a regional cultural centre, and an Easter-centric museum, Easter being a major touristic draw for the city.[68]

Puerta de Palmas

[edit]

The Puerta de Palmas was built in 1551.[69] It has two cylindrical towers flanking the entrance door. Prince Philip II and Emperor Charles V and date of construction are mentioned on the outer side of the tower. The towers are fortified with battlements and they have two decorative cords at the top and bottom levels. Its entrance is east-facing, and is double-arched and is decorated with medallions of the shield of the Emperor Charles V. It was once used as a prison, but has since undergone many renovations and has been an entrance point to the city.[69]

Real Monasterio de Santa Ana

[edit]It is a Christian monastery in Badajoz, declared a Bien de Interés Cultural site in 1988.[70] It is the headquarters of the Order of St. Clare in the city and lies in the heart of the old city. It was founded in 1518 by Ms. Leonor de Vega i Figueroa, under the blessing of Pope Leo X, and belonged to the jurisdiction of the Franciscan province of San Miguel.[70] According to the tombstone in the grounds, Figueroa was abbess of the monastery for forty years until her death on April 17, 1558. She was buried in the grounds, until moved to the Cripta Real del Monasterio de El Escorial. The monastery underwent a major transformation in the 18th century although the original structure partly remains.[70] Outwardly, part of the building has buttresses and a tower with two bells. On the vault of the chancel stands a lookout tower with a lattice brick convent, topped with pinnacles. The church of the monastery has a single nave which was rebuilt in the late 17th century, and the presbytery is covered by a late Gothic rib vault dated to the first half of the 16th century.[70] The church contains numerous altarpieces, imagery, paintings, and silverware.[70]

Gardens

[edit]

The Jardines de la Galera date back to the 10th century from the aftasids. They are nestled between the Torre de Espantaperros and the Chemin de ronde, within the Alcazaba. Many Alhambran ruins still exist within the gardens, and have been open to the public since 2007 after the site was restored after being closed for more than thirty years. The etymology of the gardens stems from the fact that the gardens provided a respite for prisoners sentenced to the gallows in Seville. Plant species extant in the gardens include cinnamomum camphora, dichondra repens, ceiba speciosa, and trees of the myrtle, laurel, orange, lemon, and pomegranate.[71] Other parks and gardens include Castelar, which has a central pond and several monuments dedicated to the romanticist writer Carolina Coronado and to Luis Chamizo Trigueros,[72] la Legión, Rivillas y Calamón, San Fernando, and La Viña.The city also has a water and leisure park, called the Lusiberia.[58]

Museums

[edit]The Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo (MEIAC) has collections of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American artists. The building is located on the site of the old Pretrial Detention and Correctional centre, which had been built in the mid-1950s on the grounds of a former 17th-century military stronghold, known as the Fort of Pardaleras.[73][74] The Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes (Provincial Museum of Fine Arts), the premier gallery of Extremadura, is set in two palatial 19th-century homes next to the Plaza de la Soledad. It is 2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft) in size, with more than 1,200 paintings and sculptures from the 16th to the 20th century representing over 350 artists such as Zurbarán, Luis de Morales, Caravaggio, [75] Flemish painters, Francisco de Goya, Felipe Checa, Torre Isunza, Eugenio Hermoso, Adelard Covarsí, Antonio Juez Nieto, Francisco Pedraja Muñoz, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí, among others.

The Museo de la Ciudad "Luis de Morales" ("Luis de Morales" City Museum) was built in what may have been the home of the Renaissance painter Luis de Morales and contains many his paintings.[12] The Museo Arqueológico Provincial (Provincial Archaeological Museum) is located within the fortress, containing pieces from all parts of the Province of Badajoz. The building houses the 16th-century palace of the dukes of Feria. The collection is organized into six major areas: prehistory, early history, Roman, Visigoth, Medieval Islam and Christian. The elegant building is built of stone and brick masonry, and has four towers at the corners with a terraced facade. The interior is made up of Mudejar brick arches resting on octagonal columns.[76]

The Museo Catedralicio (Cathedral Museum) is situated on the cathedral grounds. It provides a historical journey through the different stages of the building's construction. It also features artifacts from the founding of the archdiocese to the present day. The collections include Filipino ivories, carvings and Flemish tapestries, the tombstone of Alfonso Suárez de Figueroa, and the Custodia Procesional del Corpus of 1558. There are also works by Luis de Morales and Zurbarán.[77] The Museo Taurino (Bullfighting Museum) is located in the city centre, organized by the Extremadurian Bullfighting Club. It includes posters, photographs and objects from the world of bullfighting.[78] The Museo del Carnaval (Carnival Museum) opened in 2007 in the Menacho centre. Costumes of groups who participated over the years in the city's carnival are exhibited in the museum. In 2008, it joined the Extremadura network of museums.[79]

Plazas

[edit]

Plaza de España is in the centre of the city, the layout was designed by the city architect Rodolfo Martinez in 1917 and completed in 1920.[80] The large cathedral centers the historical area. Plaza de Cervantes is considered place of importance for the history of Badajoz. Parts of the square occupy an area which belonged to St. Andrew's Church and its cemetery. It is decorated in white marble with a concentric mosaic of pointed stars dating to 1888. Plaza Alta, recently restored, was for centuries the center of the city since it exceeded the limits of the Muslim citadel; it was formerly known simply as "the square". Spanish flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucía performed on the Plaza Alta on 10 July 2013.[81] La Giralda is located near Plaza de la Soledad.

Residential buildings

[edit]Casa Álvarez-Buiza, a private house and commercial complex, was built in the San Juan district by Adel Franco Pinna between 1918 and 1912.[82] The building located on the Plaza de La Soledad once housed the offices of the Bank of Spain.[83] Artistic elements include the use of lime, brick and colorful ceramics with an Andalusian influence. Casa del Cordón is a private house, built in the late Gothic style of the early 16th century, and has mullioned windows. It currently houses the Archdiocese. Casa Puebla, built in 1921, is one of the other designs of Pinna, who designed numerous buildings around Badajoz. It is one of the best examples of regional architecture in Andalusian style and the property has two facades, the main one featuring neo-Renaissance elements.[84]

Cemeteries

[edit]During the Visigoths period the burials, as noted from the archeological finds, were near the Picuriña, Pardaleras, and Cerro de Reyes sites. During the Arab period, burials were along the roads and near the eastern suburb of the Citadel, close to Cerro de la Muela and also in the area of Santiago bastion; these locations were noted during recent excavations. Badajocenses Christians from the earliest centuries towards the end of 19th century buried their dead in or near churches.[85]

Badajoz's oldest two cemeteries are Cementerio de San Juan and Cementerio de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. The cemeteries in active use are the Cementerio de San Juan, Cementerio Virgen de las Nieves de Balboa, Cementerio de la Inmaculada Concepción de Gévora, Cementerio San Isidro de Novelda, Cementerio Inmaculado Corazón de María de Valdebótoa and Cementerio Santiago Apóstol de Villafranco.[86] The Cementerio de San Juan is the oldest of cemeteries still in service and is dated to earlier than1839.[87][88]

Bridges

[edit]

The city of Badajoz is home to five bridges, four of which span the Guadiana.[89][90]

The Puente de Palmas, also known as Puente Viejo, is the oldest bridge in Badajoz; the masonry was first laid in 1460, but a sudden rise in the river's waters destroyed the structure in 1545.[91] It was rebuilt under D. Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, Governor of Badajoz, during the reign of Philip II of Spain. In 1603, 16 of its 24 spans were destroyed by floods and were restored between 1609 and 1612. The bridge was once again rebuilt in 1833; José María Otero was the engineer and Valentin Falcato, the architect.[91] Further improvements were made during the early 21st century, when the number of spans was increased to 32 and towers were added at both ends giving a total length of 600 metres (2,000 ft).[91] The bridge reflects the city's history with all the changes made to its spans, arches, pillars and buttresses over the centuries.

Puente de la Universidad, or Puente Nuevo, is downstream of the old Palmas Bridge. It was built in 1960.[92] Puente de la Autonomía Extremeña was completed in 1990 and is located upstream of Puente de Palmas, connecting to the major roads which lead to Madrid and to Highway N-435 Badajoz-Fregenal de la Sierra.[93] Puente Real is a suspension bridge across the Guadiana, the fourth bridge in the city which was completed in 1994 The foundation stone was laid by the King of Spain in 1992. It has six spans of viaducts of 32 metres (105 ft) each in a total bridge length of 452 metres (1,483 ft). It has a bicycle lane and links to the Elvas Avenue leading to Portugal and many other city centres.[94]

Culture and education

[edit]While not a city renowned for its culture and art, many notable artists, musicians, and writers were born in the city. Hailing from the city in the arts are the actors Luis Alcoriza, Manuel de Blas, the writers Arturo Barea, Vicente Barrantes Moreno, José López Prudencio, Emilio Morote Esquivel, Jesús García Calderón, the singers Antonio Hormigo, Rosa Morena, Federico Cabo, Guadiana Almena, La Caita, Porrina de Badajoz and the pianists Cristóbal Oudrid and Esteban Sánchez, and painters such as Luis de Morales, Antonio Vaquero Poblador, Felipe Checa, Adelardo Covarsí Yustas, and many others. The Institución Ferial de Badajoz (IFEBA), established in 2006, has not only become an important economic centre but has become a prominent regional cultural centre, and aside from trading it also regularly hosts cultural events from horse racing to break dancing to paintballing to Caribbean dancing.[54] The principal theatre in Badajoz is the Teatro López de Ayala, a grand white-painted theatre with arched windows with a capacity of 800 seats.[95] Performances of theatre, opera, concerts, and exhibitions are put on in the venue.

Like much of southern Spain, flamenco is very popular, and performances are regularly put on in Badajoz on the Plaza Alta and other venues. Some flamenco palos linked to Badajoz are Extremaduran jaleos and Extremaduran tangos. The classical music group Banda Municipal de Música, established in 1867, also performs at such venues in Badajoz and the wider province; as of 2013 it had 33 musicians.[96] In 1998 the municipal government established the Municipal School of Music in Badajoz (Escuelas Municipales de Música de Badajoz). As of 2013, classes are held in four venues in the public schools of Enrique Segura Covasí, Luis de Morales, Santo Tomás de Aquino and Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, teaching some 600 students.[97] The school teaches clarinet, flute, guitar, percussion, piano, saxophone, trumpet, violin, and singing. Cristóbal Oudrid (1825–1877), one of the founding fathers of Spanish musical nationalism, was born in Badajoz, son of the resident military bandmaster. Rosa Morena, a well-known flamenco-pop singer who was popular in the 1970s, was born in the city and still lives there; her most popular song is Échale guindas al pavo.

The festival known as "Feria de San Juan" is held every year from 23 June to 1 July at this border town, which is a major attraction not only for people of Spain but also to the Portuguese who cross the border to attend the one-week festival. This festival also includes bull fights.[59]

Badajoz is influenced by its border with Portugal. Portuguese restaurants and pastries can be found in the city, and residents often travel across the border for meals/excursions.

Badajoz is home to the Universidad de Extremadura (UNEX) Badajoz campus, situated on the west side of the river. The university was founded on 4 November 1968, when the Faculty of Badajoz belonging to the University of Seville was established.[98] Today, the University of Extremadura has branches in Badajoz, Cáceres, Mérida, and Plasencia. In 1971 the Council of Ministers approved the establishment of the College of Arts of Cáceres under the University of Salamanca. Secondary schools such as the Normal Schools of Education of Cáceres and Badajoz were integrated into the university in 1972 following the General Law of Education decree of 1970.[98] The Intermediate Technical School of Agricultural Engineering of Badajoz was founded in Badajoz 1968, renamed the College of Agricultural Engineering in 1972.[98]

Religion

[edit]

Badajoz is the see of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mérida-Badajoz. Prior to the merger of the Diocese of Mérida and the Diocese of Badajoz, Badajoz was the see of the Diocese of Badajoz from the bishopric's inception in 1255.[11] Christianity thus became the dominant religion in Badajoz and the see of the Diocese of Badajoz is based here at the Badajoz Cathedral (Cathedral of St. John the Baptist), a gothic style building which was built in 1284 in the main plaza called the Plaza de España. It underwent extensive refurbishment during the 16th to 18th centuries. The paintings of Luis de Morales, a local artist of the Renaissance period, are exhibited in the cathedral.[12] The tower of the cathedral, 41 metres (135 ft) in height, was built in the gothic style in 1542 under architect Gaspar Méndez. Built with ashlar masonry, the windows are made of stone and carved. On two of its faces clocks were fixed during the renovations carried out in 1715. The tower has a belfry and is fortified with battlements.[99] In 1827, Richard Alfred Davenport wrote a gushing description of the dean of the cathedral of Badajoz, remarking that he was "more learned than all the doctors of Salamanca, Coimbra, and Alcala, united; he understood all languages, living and dead, and was perfect master of every science divine."[100]

Adoratrices is a small chapel dedicated to St. Joseph to commemorate the arrival of Christians along with King Alfonso IX of León. The Brotherhood of St. Joseph, founded in 1556, functioned from this chapel. During the 19th-century War of Independence the chapel was bombed and its importance declined during subsequent years. However, in 1917 it was refurbished in the neo-Gothic style and now the convent Madres Adoratrices Esclavas del Santísimo y de la Caridad functions from here.[101]

The San Andres and La Concepcion churches are of the 13th century.[12] Other religious buildings include the Real Monasterio de Santa Ana, Convento de las Clarisas Descalzas, Convento de Carmelitas, Ermita de los Pajaritos, Ermita de la Soledad, Parroquia de la Concepción, Parroquia de San Agustín, Parroquia de San Andrés, Parroquia de San Juan Bautista, and the Parroquia de Santo Domingo. Ermita de la Soledad is a gothic style chapel, which was originally funded by Duke Francisco de Tutavilla y del Rufo of San Germán in 1664 in a different location.[102] It fell into ruin and was rebuilt in its present location from 1931. Parroquia de San Juan Bautista, situated in a large pink and white painted domed building dates to the 18th century, and was originally a Franciscan convent, funded by King João V of Portugal.[103]

Sports and recreation

[edit]Football

[edit]The city formerly hosted CD Badajoz, which dissolved in 2012 after finishing the season in Segunda División B Group 1.[104] Now, the city's main association football club is CD Badajoz 1905, a new club formed in 2012 by disappeared CD Badajoz supporters which is currently playing in the Regional Preferente in Extremadura, the fifth level of competition of the Spanish league football, after promotion in the 2012–13 season in the playoffs. Its stadium is Estadio Nuevo Vivero.

Cerro Reyes is currently unaffiliated with any league. Formerly, the club was a member of Segunda División B, having played their 2010–11 campaign in the division.[105] The club plays at Estadio José Pache.

Another football club based in Badajoz is Badajoz CF, a member of Tercera División – Group 14. UD Badajoz plays its home matches at Estadio Nuevo Vivero.[106]

Basketball

[edit]Badajoz's basketball club is AB Pacense, formed in 2005 from the remnants of Badajoz's dissolved basketball clubs, including CajaBadajoz, Círculo Badajoz, and Habitacle. The club competed in the Liga EBA, and calls Polideportivo La Granadilla its home arena.[107] The club was dissolved in summer 2013.

Golf

[edit]Badajoz plays host to two golf courses.[108] One, the Don Tello Golf Course, (Spanish: Club de Golf de Mérida Don Tello), is a 9-hole course constructed in 1994. The course is described as "gentle and undulating", set on the banks of the Guadiana River.[109] The second, the Guadiana Golf Course, (Spanish: Golf del Guadiana), is an 18-hole construct built in 1992. The course is described as challenging, in part due to the 14 lacustrine features and abundance of trees on the course.[110]

Transport

[edit]

Badajoz railway station, (Spanish: Estación de Tren de Badajoz), (IATA: BQZ), situated in the north of the city, is the only railway station at Badajoz. The station accommodates long-distance and medium-distance trains, both operated by the public company Renfe. It is the last Spanish railway station before the Portuguese railway system. It is expected the station will be replaced by a new facility located at the border with Portugal with high-speed services run by the Southwest–Portuguese corridor and the Madrid–Lisbon line[broken anchor]. In August 2017 Comboios de Portugal, the Portuguese national railway company, instituted a daily service from Badajoz to Entroncamento, with connections to Lisbon and Porto.[111] [112][113]

Badajoz Airport, (Spanish: Aeropuerto de Badajoz) (IATA: BJZ, ICAO: LEBZ), is located 13 km (8 mi) east of the city centre. The civilian airport shares a runway and control tower with Talavera la Real Air Base (Spanish: Base Aérea de Talavera la Real) operated by the Spanish Air Force, named after the nearby municipality of Talavera la Real.[114] The two aircraft reception facilities utilize a 2,852-metre (9,257 ft) asphalt runway. The airport currently caters for two civil routes, one to Barcelona and the other to Madrid, both operated by Air Nostrum.[115]

Healthcare

[edit]

The first hospital founded in Badajoz in 1694, was the Hospital de San Sebastián.[33]

Badajoz falls under the healthcare region of Área de Salud de Badajoz, which also includes the municipalities of Alburquerque, Alconchel, Barcarrota, Gévora, Jerez de los Caballeros, La Roca de la Sierra, Montijo, Oliva de la Frontera, Olivenza, Pueblonuevo del Guadiana, San Vicente de Alcántara, Santa Marta, Talavera la Real and Villanueva del Fresno, divided into 17 zones, seven of which are in Badajoz itself.[116] The hospitals in Badajoz are Hospital Universitario de Badajoz, Hospital Perpetuo Socorro, Hospital Materno Infantil, while clinics include Clínica "Clideba" de Capio, Clínica "Caser" de Capio, and Clínica Extremeña de Salud.[117] Hospital Universitario de Badajoz lies beyond Puente Real on the left side of the river, next to the University of Extremadura.

Notable people

[edit]- Pedro Acedo Penco (1955), politician

- Pedro de Alvarado (1485–1541), conquistador

- Estefanía Domínguez Calvo (born 1984), Spanish professional triathlete

- Manuel Godoy (1767–1851), Spanish Secretary of State

- Luis de Morales (1509–1586), painter[11]

- Rosa Morena (1941–2019), New flamenco singer

- Cristóbal Oudrid (1825–1877), pianist, conductor and composer

- Toñi Salazar (born 1963), Singer and composer

- Encarna Salazar (born 1961), Singer

- Juan Salazar (born 1954), Flamenco singer

- Enrique Salazar (1956–1982), Singer and composer

- José Salazar (1958) Singer and composer

- Pepa Bueno (1964) Newsreader, Journalist

- Hernando de Soto (1497–1542) Conquistador

Town twinning

[edit]Badajoz is twinned with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ English: UK: /ˈbædəhɒz, -hɒs/ BAD-ə-hoz, -hoss, US: /ˌbɑːdəˈhoʊz/ BAH-də-HOHZ, Spanish: [baðaˈxoθ] ; formerly written Badajos in English.

- ^ A "practicable breach" was one where two soldiers could get through side by side without needing to use their hands.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ Tarlow & Nilsson Stutz 2013, p. 377.

- ^ "Spain.info". Spain.info. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES" (PDF) (in Spanish). Cajaespana.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Erskine 2012, p. 329.

- ^ Glick 1995, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 73.

- ^ "Historia (History)" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ O'Callaghan 1983, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm 1911, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ring, Salkin & La Boda 1995, p. 74.

- ^ "Convento de San José (Adoratrices)" (in Spanish). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ a b O'Callaghan, Kagay & Vann 1998, p. 154.

- ^ a b Gallagher 1968, p. 8.

- ^ Wiltrout 1987, p. 65.

- ^ "Badajoz, Spain". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Díaz y Pérez 1887, p. 551.

- ^ Vallín 1899, p. 93.

- ^ Deutscher 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Danvers 1988, p. 39.

- ^ Fuentes del Archivo General de Indias para el estudio del conquistador Diego Valadés (in Spanish).

- ^ Villalón, M. C. (1988), En 1640, después de un prolongado período (PDF) (in Spanish), Dialnet.unirioja.es

- ^ a b Frey & Frey 1995, p. 108.

- ^ a b c "Peace Treaty of Badajoz between Portugal". Grupos de Amigos de Olivenca. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ MacFarlane 2004, p. 127.

- ^ a b Melón, Miguel Ángel (2012). "Badajoz (1811–1812) La resistencia en la frontera" (PDF). In Butró Prída, Gonzalo; Rújula, Pedro (eds.). Los sitios en la guerra de la Independencia: La lucha en las ciudades. Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz. pp. 242–244. ISBN 978-84-9828-393-8.

- ^ a b Fletcher 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Press & Slater 2006, p. 180.

- ^ "Siege of Badajoz Archived December 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Treneer 1963, p. 133.

- ^ Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art. E. Littell. 1833. p. 612. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Historia" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Kern 1995, p. 179.

- ^ Preston 2012, p. 318.

- ^ "Share on print Juan Yague". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "The flood event that affected Badajoz in November 1997" (PDF). Advances in GeoSciences. April 9, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Frey & Frey 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Yuste 1980, p. 208.

- ^ "Average Weather in Stockton, California, United States, Year Round – Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "Badajoz, Spain Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "Climate & Temperature; Badajoz". Badajoz.climatemps.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Standard climate values for Badajoz". Aemet.es. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ "Météo climat stats Moyennes 1991/2020 Espagne (page 1)" (in French). Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Extreme climate values for Badajoz". Aemet.es. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Badajoz: Población por municipios y sexo" (in Spanish). INE. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ "Guadiana del Caudillo celebra su primer año como independiente" (in Spanish). Badajoz7dias.com. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ La población de Badajoz. Fundacion BBVA. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Lúcia 1986, p. 313.

- ^ "Badajoz" (in Spanish). Elecciones.mir.es. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Diario Oficial de Extremadura del 23 de febrero de 2012. Página 3943 Archived July 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Doe.juntaex.es, accessed 9 July 2013

- ^ Información comercial española: Boletín ICE económico (in Spanish). Ministerio de Economía. 2008. p. 270. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Knight 1854, p. 461.

- ^ a b "Ferias en España en IFEBA Institución Ferial de Badajoz". Portalferias.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Inicio" (in Spanish). Feria Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Caja Badajoz construye el edificio más alto de Extremadura para su sede social" (in Spanish). Elperiodicoextremadura.com. July 9, 2007. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Nueva Sede Corporativa de la Caja de Badajoz" (in Spanish). Portal.cajabadajoz.es. November 18, 2007. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Lusiberia". Lusiberia.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 196.

- ^ Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 198.

- ^ "Plazas" (PDF) (in Spanish). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "Monuments: Alcazaba" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Tower Espantaperros" (in Spanish). Aytobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Kendrick, Michelson & Barbero 2008, p. 199.

- ^ "Fortificación Vaubán". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Apuntes para la historia de la ciudad de Badajoz: ponencias y comunicaciones (in Spanish). Editora Regional de Extremadura. 1999. p. 75. ISBN 978-84-7671-470-6. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Torre de la Soledad y La Giralda" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "La Giralda, un millón de euros más barata". Hoy.es. January 14, 2012. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Puerta de Palmas" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Historia" (in Spanish). Clarisasbadajoz.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Gardens of La Galera". TripOrg. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Carvajal 2001, p. 21.

- ^ "The Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo (MEIAC)" (in Spanish). Official website of MEIAC. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "MEIAC – Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo". Art10.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "Museo de Bellas Artes" (in Spanish). Ayuntamietno de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Museo Arqueológico" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Museo Catedralicio" (in Spanish). Ayuntamietno de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Bullfighting Museum". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "Museum of Carnival in Badajoz" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "The Arrival of the City Regional" (PDF) (in Spanish). Dialnet Unirioja. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "July". Pacodelucia.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Casa Álvarez-Buiza" (in Spanish). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ "Ejemplos de Historicismo y sus variantes". Casa Álvarez-Buiza (in Spanish). monumentosdebadajoz.es. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ "Casa Puebla" (in Spanish). Turismobadajoz.es. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ "Cementerio de Nuestra-senora-de-la-Soledad" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Cementerios Gestionados" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Los Cementerios de Badajoz Historia" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Los Cementerios de Badajoz Historia" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Sights (Badajoz)". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Bridges of Badajoz". Badajoz Ayer y Hoy. Archived from the original on August 12, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Puente de Palmas". Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Puente de la Universidad" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Puente de la Autonomía" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Puente Real" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ "Teatro López de Ayala" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Banda Municipal de Música" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Escuelas de Música" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Cómo surgió la educación universitaria en Extremadura" (in Spanish). Unex.es. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Torre de la Catedral" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Davenport 1827, p. 108.

- ^ "Adoratrices" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Ermita de la Soledad" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Parroquia de San Juan Bautista" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "El CD Badajoz, condenado a Tercera". Hoy.es. July 2012. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Cerro Reyes". Footballdatabase.eu. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "La web del UD Badajoz". UD Badajoz. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Constituida la Asociación Pacense de Baloncesto". El Periodico Extremadura. September 16, 2005. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Badajoz Golf Course". WorldGolf. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "CLUB DE GOLF DE MÉRIDA DON TELLO". Spain.info. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "GOLF DEL GUADIANA, S.A." Spain.info. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Linha do Leste - Comboios Regionais 5500 e 5501| CP". Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ "High Speed Lines Madrid – Extremadura – Portuguese Border line". ADIF. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/passenger/single-view/view/entroncamento-badajoz-passenger-service-reinstated.html Archived 3 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine Railway Gazette International

- ^ "Badajoz Airport". Airports Guides. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Badajoz Airport Routes". Aena Aeropuertos. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Mapa Sanitario del Área de Salud de Badajoz". Área de Salud de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Directorio del Área de Badajoz". Área de Salud de Badajoz. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Murillo, Ángela (April 16, 2007). "Cinco ciudades hermanas". Hoy (in Spanish). Hoy.es. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. III (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 223.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 181.

- Carvajal, Antonio Salguero (2001). Gévora: estudio de una revista poética de Extremadura (in Spanish). Diputación Provincial de Badajoz. ISBN 9788477960836.

- Danvers, Frederick Charles (1988). The Portuguese in India: Being a history of the rise and decline of their Eastern Empire. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0391-2.

- Davenport, Richard Alfred (1827). New Elegant Extracts: A Unique Selection ... from the Most Eminent Prose and Epistolary Writers ... C.& C. Whittingham.

- Deutscher, Thomas Brian (January 1, 2013). Punishment and Penance: Two Phases in the History of the Bishop's Tribunal of Novara. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4442-7.

- Díaz y Pérez, Nicolás (1887). Extremadura: (Badajoz y Cáceres). D. Cortezo y ca.

- Erskine, Andrew (November 20, 2012). A Companion to Ancient History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-58153-7.

- Fletcher, Ian (August 21, 2012). Badajoz 1812: Wellington's bloodiest siege. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-196-6.[permanent dead link]

- Frey, Linda; Frey, Marsha L. (January 1, 1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-27884-6.

- Gallagher, Patrick (January 1968). The Life and Works of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz. Tamesis Books. ISBN 978-0-900411-00-7.

- Glick, Thomas F. (1995). From Muslim Fortress to Christian Castle: Social and Cultural Change in Medieval Spain. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3349-0.

- Kendrick, Anna; Michelson, Kathryn; Barbero, Meagan (November 25, 2008). Let's Go 2009 Spain & Portugal with Morocco. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-38573-6.

- Kern, Robert (1995). The Regions of Spain: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29224-8.

- Knight, Charles (1854). The English Cyclopaedia: A New Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. Bradbury and Evans.

- Lúcia, Luis Aguiló (January 1, 1986). Decisió electoral i cultura política (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Equip de Sociologia Electoral, Edicions de La Magrana. ISBN 978-84-7410-280-2.

- MacFarlane, Charles (December 1, 2004). Memoir of the Duke of Wellington. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-1907-9.[permanent dead link]

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1983). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9264-8.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F.; Kagay, Donald J.; Vann, Theresa M. (1998). On the Social Origins of Medieval Institutions: Essays in Honor of Joseph F. O'Callaghan. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11096-0.

- Press, Ivy; Slater, Tom (2006). Heritage Americana Grand Format Auction Catalog #629. Heritage Capital Corporation. ISBN 978-1-59967-082-9.

- Preston, Paul (March 22, 2012). The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-746722-8.

- Tarlow, Sarah; Nilsson Stutz, Liv (June 6, 2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956906-9.

- Treneer, Anne (1963). The Mercurial Chemist: A Life of Sir Humphry Davy. Methuen.

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; La Boda, Sharon (1995). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2.

- Wiltrout, Ann E. (January 1, 1987). A Patron and a Playwright in Renaissance Spain: The House of Feria and Diego Sánchez de Badajoz. Tamesis. ISBN 978-0-7293-0254-8.

- Vallín, Acisclo Fernández (1899). Discursos leídos ante la Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales. Establecimiento tipográfico "Sucesores de Rivadeneyra". p. 93.

- Yuste, Abelardo de Unzueta y (1980). Estructura económica de España (in Spanish). A. de Unzueta y Yuste. ISBN 9788430031443.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Spanish)

- Universidad de Extremadura website Archived July 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Real Monasterio de Santa Ana website (in Spanish)