Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

Diocese of Peoria Diœcesis Peoriensis | |

|---|---|

Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Territory | 26 counties across central Illinois |

| Ecclesiastical province | Chicago |

| Metropolitan | Chicago |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 16,933 sq mi (43,860 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2015) 1,492,335 121,965 (8.2%) |

| Parishes | 158 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | February 12, 1875 (149 years ago) |

| Cathedral | St. Mary's Cathedral |

| Patron saint | [citation needed] |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Louis Tylka |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Blase J. Cupich |

| Vicar General | Philip D. Halfacre |

| Bishops emeritus | Daniel R. Jenky |

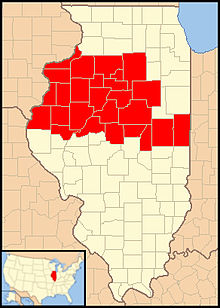

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| cdop.org | |

The Diocese of Peoria (Latin: Diœcesis Peoriensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory, or diocese, of the Catholic Church in the north central region of Illinois in the United States. It is a suffragan diocese within the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Chicago.

The current bishop of the Diocese of Peoria is Louis Tylka.[1] The mother church of the diocese is the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Peoria.

Territory

[edit]The Diocese of Peoria comprises the following Illinois counties:

Bureau, Champaign, DeWitt, Fulton, Hancock, Henderson, Henry, Knox, LaSalle, Livingston, Logan, Marshall, Mason, McDonough, McLean, Mercer, Peoria, Piatt, Putnam, Rock Island, Schuyler, Stark, Tazewell, Vermilion, Warren and Woodford.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]1670 to 1776

[edit]During the 17th century, present day Illinois was part of the French colony of New France. The Diocese of Quebec, which had jurisdiction over the colony, sent numerous French missionaries to the region.

Catholicism in the Peoria area dates from the days of the French missionary Jacques Marquette, who rested at the Native American village of Peoria on his voyage up the Illinois River in 1673. Opposite present day Peoria, the French explorers Robert de La Salle and Henri de Tonti in 1680 built Fort Crèvecoeur. Mass was celebrated there by three French Recollect Fathers: Gabriel Ribourdi, Zenobius Membre, and Louis Hennepin. With some breaks in the succession, the line of missionaries extends to within a short period of the founding of modern Peoria. After the British took control of New France in 1763, the Archdiocese of Quebec retained jurisdiction in the Illinois area.

1776 to 1875

[edit]In 1776, the new United States claimed sovereignty over the area of Illinois. After the American Revolution ended in 1783, Pope Pius VI erected in 1784 the Prefecture Apostolic of the United States, encompassing the entire territory of the new nation. In 1785, Bishop John Carroll sent his first missionary to Illinois. In 1787, the area became part of the Northwest Territory of the United States. Pius VI created the Diocese of Baltimore, the first diocese in the United States, to replace the prefecture apostolic in 1789.[2][3]

With the creation of the Diocese of Bardstown in Kentucky in 1810, supervision of the Illinois missions shifted there from the Diocese of Baltimore. In 1827, the Diocese of St. Louis assumed jurisdiction over the western half of the new state of Illinois. In 1834, the Vatican erected the Diocese of Vincennes, which included eastern Illinois.[4] In 1839, Father Raho, an Italian priest, visited Peoria, remaining long enough to build the old stone church in Kickapoo.

In 1843, the Vatican erected the Diocese of Chicago, taking the Illinois parishes from the Dioceses of St. Louis and Vincennes. St. Mary's, the first Catholic church in Peoria proper, was erected by John A. Drew in 1846. Among his successors as pastor of St. Mary's was the poet, Abram J. Ryan.

Many of the early Irish immigrants in Illinois in the mid-1800s came to work on the Illinois and Michigan Canal Owing to the failure of the contracting company, the workers received their pay in land scrip instead of cash, forcing them to settle on virgin farm land. These Irish farmers joined the existing German immigrants. They were followed by Poles, Slovaks, Slovenians, Croats, Lithuanians, and Italians who came to work in the coal mines. These groups were organized in ethnic parishes with priests of their own nationalities. In 1851, the first Catholic Church in Rock Island, St. James, was opened.[5]

Diocese of Peoria

[edit]1875 to 1930

[edit]

Due to the rapid growth of the Catholic population in central Illinois in the late 19th century, Coadjutor Bishop Thomas Foley of Chicago became concerned about his ability to govern that region along with Chicago. He requested that the Vatican divide the Diocese of Chicago in 1872, but the Vatican did not act on it. After another appeal to the Vatican in 1874, Pope Pius IX on February 12, 1875, erected the new Diocese of Peoria, taking 23 counties from the Diocese of Chicago. The new diocese was bounded on the west by the Mississippi River and on the east by the Indiana border. Peoria was chosen as the see city.

Pius IX appointed John Spalding of the Diocese of Louisville as the first bishop of Peoria in 1876. That same year, six Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis arrived from Iowa City, Iowa, to care for the sick. They served at the city hospital and made home visits to patients. Shortly after the nuns' arrival, Spalding visited the city hospital. Observing their difficult working conditions, he encouraged them to form a separate congregation with his support. The Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis of Peoria was established in July 1877. St. Francis Hospital opened in Peoria 1878.[6] Stricken with paralysis in 1905, Spalding resigned as bishop in 1908.[7]

Pope Pius X named Edmund Dunne of the Archdiocese of Chicago as the second bishop of Peoria. During the early 1920s, the future Archbishop Fulton Sheen, a popular television host in the 1950s, was a priest in the diocese. After Sheen spent time in pastoral and teaching jobs in the United Kingdom, Dunne ordered him to return to Peoria in 1925. Both Columbia University in New York City and Oxford University in England offered Sheen teaching positions. However, instead of allowing Sheen to take one of these prestigious positions, Dunne assigned him as a curate to St. Patrick's, a poor parish in Peoria. Sheen took the assignment without any complaints and later said he enjoyed his time there.[8] Nine months later, Dunne summoned Sheen to his office. Dunne told him:

I promised you to Catholic University over a year ago. They told me that with all your traipsing around Europe, you'd be so high hat you couldn't take orders. But Father Cullen says you've been a good boy at St. Patrick's. So run along to Washington.[8]

1930 to 1990

[edit]After Dunn died in 1929, Pope Pius XI replaced him in 1930 with Joseph Schlarman. In 1951, he died after 20 years as bishop of Peoria. Auxiliary Bishop William Cousins was the next bishop of the diocese, named by Pope Pius XII in 1952. During his tenure as bishop, Cousins established five new parishes and six new grade schools.[9] Pope John XXIII named Cousins as archbishop of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee in 1958.

To replace Cousins, Pope John XXIII appointed Bishop John Franz from the Diocese of Dodge City in 1959. As bishop, Franz created 17 new grade schools, two new high schools, one Newman Centre, four new parishes, four missions, and elevate eight missions to parish status. He retired in 1971 and Pope Paul VI named Edward O'Rourke to replace Franz.

O'Rourke sold the episcopal residence on Glen Oak Avenue and moved to a one-bedroom brick ranch house near St. Mary's Cathedral, donating the money to the diocesan fund for retired priests.[10] He established the first Diocesan Pastoral Council in 1974.[10] That same year he established he replaced the old system of six deaneries by dividing the diocese into fifteen vicariates. He ordained the first permanent deacons of the diocese in 1976.[10]

O'Rourke established the Annual Stewardship Appeal (now known as the Annual Diocesan Appeal) and the Teens Encounter Christ program.[10] He consolidated Costa Catholic School in Galesburg, Illinois, (1972), Jordan Catholic School in Rock Island, Illinois, (1974), La Salle Catholic School (1978) and Peoria Notre Dame High School (1988).[10] In 1987, Pope John Paul II appointed John J. Myers as coadjutor bishop of the Diocese of Peoria to assist Bishop Edward O'Rourke.[11]

1990 to present

[edit]

When O'Rourke retired in 1990 after 19 years as bishop, Myers automatically succeeded him. While bishop, Myers issued an order forbidding Catholic hospitals in the diocese from providing emergency contraception to rape victims, a restriction he later eased.[12] He also fired a teacher at a Catholic high school for inviting a speaker to discuss the ordination of women to the priesthood.[12] During Myers' tenure, the diocese saw a rapid increase in vocations to the priesthood, with many seminarians being drawn to his more conservative theology.[13] In 2001, John Paul II appointed Myers as archbishop of the Archdiocese of Newark. John Paul II named Auxiliary Bishop Daniel R. Jenky of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend as the new bishop of Peoria.

As bishop, Jenky led the canonization cause of Archbishop Sheen. However, in 2014, citing undocumented verbal agreements, Jenky announced that he would not permit the cause to progress until Sheen's remains were transferred to Peoria from St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City.[14][15] After three years of litigation between the diocese and the Archdiocese of New York regarding Sheen's wishes, the court ordered his remains to go to Peoria, where they arrived in June 2019.[16]

On May 11, 2020, Pope Francis named Louis Tylka of the Archdiocese of Chicago as coadjutor bishop of the diocese. When Jenky retired in 2022, Tylka automatically became the new and current bishop of Peoria.

Sexual abuse

[edit]In August 2013, the Diocese of Peoria settled a sexual abuse lawsuit for $1.35 million. The plaintiff, Andrew Ward, had accused Reverend Thomas Maloney of molesting him during the 1990s when he was eight years old.[17] The lawsuit claimed that Bishop Myers allowed Maloney to remain in ministry, despite evidence of prior sexual abuse. Maloney was later accused of sexual abuse by three more victims.[18]

In February 2018, Bishop Jenky was sued along with the other Catholic bishops in Illinois. Two of the plaintiffs claimed sexual abuse by priests in the Diocese of Peoria during the 1970s and 1980s. Attorney for the plaintiffs accused Jenky of providing incomplete lists of priests who were considered credibly accused of sexual abuse. The diocese denied the charges.[19]

In November 2018, the diocese removed three retired priests, Reverend George Hiland, Reverend Duane Leclercq, and Reverend John Onderko, from public ministry after determining that all three had credible accusations of sexual abuse of minors.[20]

- The diocese had received accusations against Hiland as early as 1993. One victim, known as "Peter", said that he was abused as a seventh grader during the 1960's in Hiland's car, in the woods and in a cemetery.[21]

- When teaching at Trinity High School in Bloomington, Leclercq would frequently grab boys by the crotch in the hallways. He was arrested in 1985 after a boy made an abuse accusation to the police. Myers, then vicar general for the diocese, went to the police station and succeeded in getting Leclercq's charges dropped.

- Onderko faced a sexual abuse allegation from 1964. Claiming that the diocese never told him the accusation, Onderko sued the diocese for defamation in 2020.[22]

In May 2023, Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul released an investigative report about sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy in Illinois.[23] For the Diocese of Peoria, Raoul reported 51 priests with credible accusations of sexual abuse by 142 accusers.[24][25] The diocese said that none of these priests were still in ministry and all of them had been reported to authorities.[26]

Bishops

[edit]Bishops of Peoria

[edit]- John Lancaster Spalding (1876–1908)

- Edmund Michael Dunne (1909–1929)

- Joseph Henry Leo Schlarman (1930–1951), appointed archbishop ad personam in 1951

- William Edward Cousins (1952–1958), appointed Archbishop of Milwaukee

- John Baptist Franz (1959–1971)

- Edward William O'Rourke (1971–1990)

- John Joseph Myers (1990–2001; coadjutor 1987–1990), appointed Archbishop of Newark

- Daniel Robert Jenky (2002–2022)

- Louis Tylka (2022–Present; coadjutor 2020–2022)

Auxiliary bishops

[edit]Peter Joseph O'Reilly (1900-1923)

Other diocesan priests who became bishops

[edit]- Gerald Thomas Bergan, appointed bishop of Des Moines and later archbishop of Omaha

- Fulton J. Sheen, appointed auxiliary bishop of New York and later bishop of Rochester, and elevated to archbishop (titular archbishop of the historic Archdiocese of Newport in Wales)[27] upon retirement in 1969

Education

[edit]The diocese has 31 elementary schools and seven high schools.

High schools

[edit]- Alleman High School – Rock Island

- Central Catholic High School – Bloomington

- Marquette High School – Ottawa

- Peoria Notre Dame High School – Peoria

- St. Bede Academy – Peru

- St. Thomas More High School – Champaign

- Schlarman Academy – Danville

The Catholic Post

[edit]In 1934, the diocese established a newspaper called The Peoria Register. It originally was part of a chain of diocesan newspapers printed in Denver. In 1969, production and printing of the paper were moved within the diocese and the name was changed to The Catholic Post. After 90 years, the paper published its final edition on Dec. 24, 2023.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Peoria (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ "Our History". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ "Freedom of Religion Comes to Boston | Archdiocese of Boston". www.bostoncatholic.org. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Thompson, Joseph J. (1927). "Diocese of Springfield in Illinois; diamond jubilee history" (PDF). University of Illinois. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- ^ THAE.CO. "St. Joseph's Church » RIPS". Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ OSF Healthcare

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia article

- ^ a b Farney, Kirk D. (2022-06-21). Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-1-5140-0323-7.

- ^ "Previous Bishops". Catholic Diocese of Peoria.

- ^ a b c d e "Most Reverend Edward W. O'Rourke". Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010.

- ^ "Archbishop John Joseph Myers [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Kocieniewski, David (May 30, 2004). "An Archbishop's Hard Line Courts Loyalty and Conflict". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Priesthood Plays in Peoria as Recruiting Thrives : Clergy: Diocese has ordained more men in the last year than dioceses 10 times its size. Much of the credit goes to a conservative bishop who cultivates aspiring priests". Religious News Service. L.A. Times. July 6, 1991. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ Sharon Otterman (11 June 2019). "An Archbishop Could Become a Saint. But First, His Body Must Be Moved". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Sheen cause suspended, call for prayer". The Catholic Post (Press release). September 3–5, 2014. Archived from the original on September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Remains of Venerable Archbishop Sheen transferred; beatification cause resumes". The Catholic Post (Press release). 27 June 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ NJ.com, Mark Mueller | NJ Advance Media for (August 13, 2013). "Church pays $1.35 million in suit alleging Newark archbishop protected abuser in Illinois". nj. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Peoria diocese pays $1.35 million to settle suit against Archbishop Myers | News Headlines". www.catholicculture.org. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Eric Stock; Ryan Denham (2018-10-18). "Illinois Catholic Bishops Sued Over Alleged Sex Abuse Cover-Up". NPR Illinois. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- ^ "Sexual abuse allegations force 3 Peoria priests from public ministry". wqad.com. November 1, 2018. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ "George H. Hiland | Narrative". clergyreport.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ "Accused Priest in Rock Island Sues Peoria Diocese: I Am Innocent, by Linda Cook, Quad Cities Online, March 10, 2020". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ "Diocese of Peoria | Diocese". clergyreport.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "Abusive Clerics and Religious Brothers". clergyreport.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ Bullock, JJ (2023-06-05). "Sweeping investigation reveals decades of scandals within Catholic Diocese of Peoria". Peoria Journal Star. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ Stevenson, Will; Packowitz, Howard (2023-05-23). "Catholic Diocese of Peoria releases statement on IL AG's sex abuse report". www.25newsnow.com. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ "Pope Francis just named an archbishop 'ad personam.' What the heck is that?". pillarcatholic.com. 2021-07-06. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

- ^ "Diocese of Peoria, Ill., shuts down The Catholic Post newspaper after 90 years". National Catholic Reporter. January 17, 2024. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

Sources

[edit]External links

[edit]- Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria Official Site

- Profile of Bishop Daniel R. Jenky

- Catholic Hierarchy

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.