King-Emperor

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

The 'R' and 'I' after his name indicate 'King' and 'Emperor' in Latin ('Rex' and 'Imperator').

A king-emperor or queen-empress is a sovereign ruler who is simultaneously a king or queen of one territory and emperor or empress of another. This title usually results from a merger of a royal and imperial crown, but recognises the two territories as different politically and culturally as well as in status (emperor being a higher rank than king). It also denotes a king's imperial status through the acquisition of an empire or vice versa.

The dual title signifies a sovereign's dual role, but may also be created to improve a ruler's prestige. Both cases, however, show that the merging of rule was not simply a case of annexation where one state is swallowed by another, but rather of unification and almost equal status, though in the case of the British monarchy the suggestion that an emperor is higher in rank than a king was avoided by creating the title "king--emperor" or "queen-empress" instead of "emperor-king" or "empress-queen".

In Austria-Hungary

[edit]Another use of this dual title was in 1867, when the multi-national Austrian Empire, which was German-ruled and facing growing nationalism, undertook a reform that gave nominal and factual rights to Hungarian nobility. This reform revived the Austrian-annexed Kingdom of Hungary, and therefore created the dual-monarchic union state of Austria-Hungary and the dual title of "emperor-king" (in German Kaiser und König, in Hungarian Császár és Király).

The Habsburg dynasty therefore ruled as Emperors of Austria over the western and northern half of the Empire (Cisleithania), and as Kings of Hungary over the Kingdom of Hungary and much of Transleithania. Hungary enjoyed some degree of self-government and representation in joint affairs (principally foreign relations and defence). The federation bore the full name of "The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen".

In the Italian colonial empire

[edit]Following the Italian occupation of Ethiopia in 1936, King Victor Emmanuel III was proclaimed Emperor of Ethiopia. Thus, he became the King-Emperor (in Italian Re Imperatore), ruling over both the Kingdom of Italy and the Ethiopian Empire.

The King-Emperor was represented by the Viceroy, who was also appointed as Governor-General of Italian East Africa (AOI – Africa Orientale Italiana). The capital city of the Viceroy and Governor-General was Addis Ababa.

In the German Empire

[edit]In 1871, the North German Confederation united with the Southern German states to form the German Empire. The Constitution stated that the King of Prussia, then William I, would be crowned German Emperor (Deutscher Kaiser). William wanted to be proclaimed Emperor of Germany (Kaiser von Deutschland), but this would have caused sovereignty problems with the southern German princes and also with Austria.

After the devastating loss in the First World War and the German Revolution, Emperor William II attempted to abdicate the throne of Germany while retaining his throne as King of Prussia, believing the Kingdom of Prussia and the German Empire to be in a personal union. But after being informed that he could not abdicate one throne without the other, William was forced to abdicate both thrones and lived the rest of his live in exile in the Netherlands.

In the British Empire

[edit]

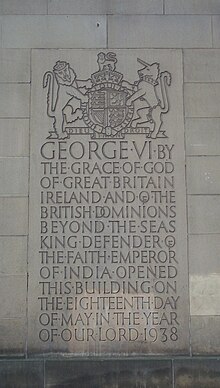

The British Crown had officially taken over the governing of British India from the East India Company in 1858, in the aftermath of what the British called 'the Indian Mutiny'. Henceforth, India (including British India and the Princely States) was ruled directly from Whitehall via the India Office. In 1876, Queen Victoria was recognized as Empress of India by the British Government, via the Royal Titles Act 1876; this title was proclaimed in India at the Delhi Durbar of 1877. She was thus the Queen-Empress, and her successors, until George VI, were known as King-Emperors. This title was the shortened form of the full title, and in widespread popular use.

The reigning King-Emperors or Queen-Empress used the initials R I (Rex Imperator or Regina Imperatrix) or the abbreviation Ind. Imp. (Indiae Imperator/Imperatrix) after their name (while the one reigning Queen-Empress, Victoria, used the initials R I, the three consorts of the married King-Emperors simply used R).

British coins, and those of the British Empire and Commonwealth dominions, routinely included some variation of the titles Rex Ind. Imp., although in India itself the coins said "Empress", and later "King Emperor." When, in August 1947, India became independent, all dies had to be changed to remove the latter two abbreviations, in some cases taking up to a year. In the United Kingdom, coins of George VI carried the title to 1948.

Titles

[edit]- When the Goryeo dynasty, Korean people sometimes referred to their kings as the "Holy Emperor-King" (神聖帝王, 신성제왕).[1]

- The Serbian emperor Stefan Dušan (r. 1346–55), who started off as king (1331–46), is attested with the title "Emperor of Greece and King of All Serb Lands and the Maritime" in a document dating to between 1347 and 1356 (see also Emperor of the Serbs).[2][3]

- The Holy Roman Emperors were also Kings of Italy, Bohemia, Germany, Burgundy, and/or Hungary for most of the time that title existed.

- Napoleon was simultaneously Emperor of the French and King of Italy. His title was shortened to "Emperor-King" (Empereur-Roi or l'Empereur et Roi) rather than "King-Emperor".

- John VI of Portugal was made titular Emperor of Brazil alongside being King of Portugal and was titled King-Emperor until his death. After John VI's death, his son Pedro briefly succeeded him as King of Portugal while reigning as Emperor of Brazil.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 강효백 (2020-12-11). "[강효백의 新 아방강역고-7] 고려는 황제국 스모킹건12(3)". Aju Business Daily (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-08-22.

- ^ Miklosich, Franz (1858). Monumenta serbica spectantia historiam Serbiae, Bosnae, Ragusii ed: Fr. apud Guilelmum Braumüller. p. 154.

- ^ James Evans (30 July 2008). Great Britain and the Creation of Yugoslavia: Negotiating Balkan Nationality and Identity. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-85771-307-0.