Records of prime ministers of the United Kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

The article lists the records of prime ministers of the United Kingdom since 1721.

Period of service

[edit]

Longest term

[edit]The prime minister with the longest single term was Robert Walpole, lasting 20 years and 315 days from 3 April 1721 until 11 February 1742.[1] This is also longer than the accumulated terms of any other prime minister.

Shortest term

[edit]Liz Truss holds the record for the shortest unequivocal term of office, at 49 days. She was appointed by Elizabeth II at Balmoral Castle on 6 September 2022, and officially resigned as prime minister to Charles III at Buckingham Palace on 25 October 2022. George Canning holds the record for the second shortest term in office, dying in office on 8 August 1827, 119 days after his appointment.

However, the record of the shortest term may depend on the criteria used. Lord Bath technically assumed office for only two days (10–12 February 1746), but was unable to find more than one person who would agree to serve in his cabinet. A satirist of the time wrote: "the minister to the astonishment of all wise men never transacted one rash thing; and, what is more marvellous, left as much money in the Treasury as he found in it." James Waldegrave, 2nd Earl Waldegrave was a prime minister for four days, 8–12 June 1757. However, neither Pulteney or Waldegrave formed an effective government, and so there are other contenders for the record of shortest term of office.

In November 1834, the Duke of Wellington declined to become prime minister for a second term, but formed a "caretaker" administration for 25 days (17 November – 9 December 1834) while his recommendation for the post, Robert Peel, returned from Europe. This caretaker administration is not necessarily considered a term of office in its own right, however.

Period between first and last day as PM

[edit]The prime minister with the longest period between the start of their first appointment and the end of their final term was the Duke of Portland, whose first term began on 2 April 1783 and whose second and final term ended on 4 October 1809, a period of about 26 years and 6 months.

Intervals between terms of office

[edit]The Duke of Portland was out of office between his two terms for 23 years and 101 days, from 19 December 1783 to 31 March 1807.

The shortest interval (or "fastest comeback") was achieved by Henry Pelham, who resigned on 10 February 1746 but returned to office two days later (12 February) when Lord Bath had been invited to form a ministry but failed to do so. The shortest interval where an intervening ministry had been formed was achieved by Lord Melbourne, who was out of office after being dismissed on 14 November 1834, but returned 155 days (under six months) later, following the end of successor Robert Peel's first ministry on 18 April 1835.

Number of terms

[edit]A prime minister's "term" is traditionally regarded as the period between the appointment and resignation, dismissal, or death, with the number of general elections taking place in the intervening period making no difference.

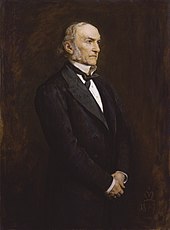

The only prime minister to serve four terms under that definition was William Ewart Gladstone:

- 3 December 1868 – 20 February 1874

- 23 April 1880 – 23 June 1885

- 1 February – 25 July 1886

- 15 August 1892 – 5 March 1894

Three prime ministers have served three terms:

- The Earl of Derby

- 23 February 1852 – 17 December 1852

- 20 February 1858 – 11 June 1859

- 28 June 1866 – 25 February 1868

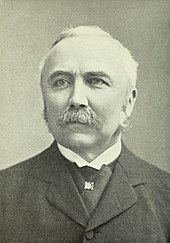

- The Marquess of Salisbury

- 23 June 1885 – 28 January 1886

- 25 July 1886 – 11 August 1892

- 25 June 1895 – 11 July 1902

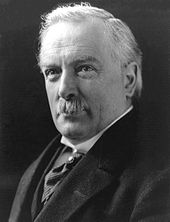

- Stanley Baldwin

- 22 May 1923 – 22 January 1924

- 4 November 1924 – 4 June 1929

- 7 June 1935 – 28 May 1937

Thirteen prime ministers have served two terms: Winston Churchill, Benjamin Disraeli, Ramsay MacDonald, The Viscount Melbourne, The Duke of Newcastle, Lord Palmerston, Robert Peel, William Pitt the Younger, The Duke of Portland, The Marquess of Rockingham, Lord John Russell, The Duke of Wellington, and Harold Wilson.

Terms of PMs and reigns of sovereigns

[edit]The office of prime minister has coincided with the reigns of twelve British monarchs (including a Regency during the incapacity of George III from 1811 to his death in 1820), to whom the prime minister has been constitutionally head of government to the sovereign's headship of state.

Until 1837, the death of a sovereign led to Parliament being dissolved within six months which led to a general election. The results of such elections were:

- 1727 – Robert Walpole held

- 1761 – the Duke of Newcastle held

- 1820 – Lord Liverpool held

- 1830 – the Duke of Wellington defeated, Lord Grey appointed

- 1837 – Lord Melbourne held

Served under most sovereigns

[edit]Stanley Baldwin is the only prime minister to have served three sovereigns, in succession: King George V, King Edward VIII, and King George VI.

Ten prime ministers served under two sovereigns, nine through being in office at transitions between reigns.

- Robert Walpole — George I and George II

- The Duke of Newcastle — George II and George III

- Lord Liverpool — George III and George IV

- The Duke of Wellington — George IV and William IV

- Lord Melbourne — William IV and Queen Victoria

- Robert Peel — William IV and Queen Victoria (not in office during transition of reign)

- Lord Salisbury — Queen Victoria and Edward VII

- H. H. Asquith — Edward VII and George V

- Winston Churchill — George VI and Elizabeth II

- Liz Truss — Elizabeth II and Charles III

Number of PMs serving during reign

[edit]- Elizabeth II – 15, from Winston Churchill to Liz Truss

- George III – 14, from the Duke of Newcastle to Lord Liverpool

- Victoria – 10, from Lord Melbourne to Lord Salisbury

- George II – 5, from Robert Walpole to the Duke of Newcastle

- George V – 5, from H. H. Asquith to Stanley Baldwin

- George IV – 4, from Lord Liverpool to the Duke of Wellington

- William IV – 4, from the Duke of Wellington to Lord Melbourne

- Edward VII – 4, from Lord Salisbury to H. H. Asquith

- George VI – 4, from Stanley Baldwin to Winston Churchill

- Charles III – 3, from Liz Truss to Keir Starmer

- George I – 1, Robert Walpole

- Edward VIII – 1, Stanley Baldwin

PMs born during reigns in which they held office

[edit]Ten prime ministers have served office under sovereigns in whose own reigns they were born.

King George III (reigned 1760–1820)

[edit]- Spencer Perceval – born 1762, served 1809–1812 – was assassinated in 1812; his is the only complete lifetime lived by a prime minister under a single sovereign

- Lord Liverpool – born 1770, served 1812–1827

Queen Victoria (reigned 1837–1901)

[edit]- Lord Rosebery – born 1847, served 1894–1895

Queen Elizabeth II (reigned 1952–2022)

[edit]- Sir Tony Blair – born 1953, served 1997–2007

- David Cameron – born 1966, served 2010–2016

- Theresa May – born 1956, served 2016–2019

- Boris Johnson – born 1964, served 2019–2022

- Liz Truss – born 1975, served 2022

Cameron, Johnson, and Truss have the additional distinction of being younger than all of Elizabeth II's children.

PMs who lived under most reigns

[edit]Both Robert Walpole (1676–1745) and Lord Wilmington (c. 1673–1743) lived under the reigns of the same seven sovereigns: Charles II, James II, joint sovereigns William III and Mary II, Queen Anne, George I, and George II.

Winston Churchill (1874–1965), Clement Attlee (1883–1967), Anthony Eden (1897–1977) and Harold Macmillan (1894–1986) all lived under the reigns of the same six sovereigns: Victoria, Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII, George VI and Elizabeth II.

Time between the start or end of a monarch's reign and the appointment of a prime minister

[edit]The record for the prime minister appointed latest into a monarch's reign is held by Liz Truss, who was appointed 70 years and 7 months into the reign of Elizabeth II. She also holds the record for the prime minister appointed closest to the end of a monarch's reign, being appointed two days before the death of Elizabeth II.

The record for the prime minister appointed soonest into the reign of a monarch goes to Rishi Sunak, the immediate successor of Liz Truss, appointed 47 days into the reign of Charles III.

These records all come about largely due to (but are not inherently dependent on) the unique circumstance of the end of Elizabeth II's record-breaking long reign coinciding with the start of Liz Truss' record-breaking short term. Various other records can be derived from these facts, such as the shortest time between the end of a prime minister's term and end of a monarch's reign being the 2 days between the resignation of Boris Johnson and death of Elizabeth II, or the shortest time between the start of a monarch's reign and end of a prime minister's term being the 47 days between the ascension of Charles III and the resignation of Liz Truss.

Age

[edit]Age at appointment

[edit]

The youngest prime minister to be appointed was William Pitt the Younger on 19 December 1783 at the age of 24 years and 208 days.

The oldest prime minister to be appointed for the first time was Lord Palmerston on 6 February 1855 at the age of 70 years and 109 days.

The oldest prime minister to be appointed overall, and oldest to win a General Election, was William Ewart Gladstone, who was born on 29 December 1809 and appointed for the final time on 15 August 1892 at the age of 82 years and 231 days, following that year's General Election.

Age on leaving office

[edit]The youngest prime minister to leave office was the Duke of Grafton, who retired in 1770, aged 34. The oldest was Gladstone, who was 84 years at the time of his final retirement in 1894.

Age differences of outgoing and incoming PMs

[edit]Greatest age difference – Lord Rosebery (born 7 May 1847) was 37 years, 129 days younger than William Ewart Gladstone (born 29 December 1809) whom he succeeded after the final retirement of the latter in 1894.

Smallest age difference – George Canning (born 11 April 1770) was 57 days senior to Lord Liverpool (born 7 June 1770), whom he succeeded after Liverpool retired in 1827. Canning and Liverpool were one of four pairs of immediately consecutive prime ministers who shared a birth year, the others being:

- William Pitt the Younger (served 1783–1801 and 1804–1806) and Lord Grenville (served 1806–1807), both born in 1759

- Lord Aberdeen (served 1852–1855) and Lord Palmerston (served 1855–1858 and 1859–1865), both born in 1784

- Harold Wilson (served 1964–1970 and 1974–1976) and Edward Heath (served 1970–1974), both born in 1916

The decade of the 1730s was the most productive for births of future prime ministers, with five: Lord Rockingham (born 1730, served 1765–1766 and 1782), Lord North (born 1732, served 1770–1782), the Duke of Grafton (born 1735, served 1768–1770), Lord Shelburne (born 1737, served 1782–1783), and the Duke of Portland (born 1738, served 1783 and 1807–1809).

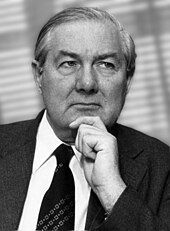

Longest-lived

[edit]The longest-lived prime minister was James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, who was born on 27 March 1912 and died on 26 March 2005 at the age of 92 years 364 days, which was the day before his 93rd birthday. Prior to this the longest-living prime minister was Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, who was born on 10 February 1894 and died on 29 December 1986 (aged 92 years, 322 days). Alec Douglas-Home is the only other prime minister to have lived into his ninety-third year (he died on 9 October 1995 at 92 years, 99 days).

Of the eight former prime ministers currently alive, the oldest is John Major (born 29 March 1943), who is 81 years old. If he lives up to 28 March 2036, he will surpass Callaghan's record and he will become the longest-lived prime minister.

Shortest-lived

[edit]The shortest-lived prime minister was the Duke of Devonshire, who was born on 8 May 1720 and died on 2 October 1764 at the age of 44 years and 147 days.

Longest-lived after office

[edit]The prime minister who lived the longest after leaving office for the final time was the Duke of Grafton, who left office on 28 January 1770. He died on 14 March 1811, 41 years and 45 days later.

In the last 100 years, the prime minister who lived the longest after leaving office was Edward Heath, whose term ended on 4 March 1974. He died on 17 July 2005, 31 years and 135 days later.

Shortest-lived after office

[edit]

The prime minister who lived the shortest period after leaving office was Henry Campbell-Bannerman, who resigned on 3 April 1908 and died just 19 days later on 22 April 1908, while still resident in 10 Downing Street.

General elections

[edit]Most PMs in office between general elections

[edit]There have been two intervals between general elections, both in the 18th century, when on both occasions five successive prime ministers were in office.

- Between the general elections of 1761 and 1768: the Duke of Newcastle (resigned 26 May 1762), Lord Bute (resigned 8 April 1763), George Grenville (resigned 10 July 1765), Lord Rockingham (resigned 30 July 1766) and Lord Chatham (until dissolution of the parliament).

- In the shorter interval between the general elections of 1780 and 1784: Lord North (resigned 27 March 1782), Lord Rockingham (second ministry, died in office 1 July 1782), Lord Shelburne (resigned 26 March 1783), the Duke of Portland (resigned 18 December 1783) and William Pitt the Younger (until dissolution of the parliament).

In modern times, since members of the House of Lords ceased to hold prime ministerial office (after 1902), there have been two occasions where there were three prime ministers in office between general elections:

- Between the general elections of 1935 and 1945: Stanley Baldwin (retired 28 May 1937), Neville Chamberlain (resigned 10 May, and subsequently died 1940) and Winston Churchill (until dissolution of the parliament). It is important to note that this was an unusually long period between general elections, with the election due in 1940 not being held as a consequence of the Second World War.

- Between the general elections of 2019 and 2024: Boris Johnson (resigned 6 September 2022), Liz Truss (resigned 25 October 2022), and Rishi Sunak (until dissolution of the parliament).

Most general elections contested as party leader

[edit]The most general elections contested by an individual is six. H. H. Asquith contested the January 1910, December 1910, 1918, 1922, 1923 and the 1924 general elections.

The most general elections lost by an individual is four. Charles James Fox was unsuccessful after contesting the 1784, 1790, 1796 and 1802 general elections, and subsequently never became prime minister. The most general elections won by an individual is four. Robert Walpole, Lord Liverpool, William Ewart Gladstone, and Harold Wilson each won four general elections.

Age at losing a general election

[edit]The youngest person to be on the losing side at a general election was Charles James Fox, who led his Whig Party to defeat in the 1784 general election when aged 35. The youngest prime minister to be on the losing side at a general election was Rishi Sunak, at 44 years and 54 days when the Conservative Party lost the 2024 general election.

William Ewart Gladstone, was the oldest, at 76 years, when his party lost the 1886 general election, although he returned to office in 1892. The oldest prime minister to be defeated without returning to office was Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, who was 75 when the Conservative Party lost the 1880 general election. Aged 70 years, 200 days, Jeremy Corbyn is the oldest person to be on the losing side of a general election without ever becoming prime minister when the Labour Party lost the 2019 general election.

Age at winning a general election

[edit]The youngest prime minister to be on the winning side at a general election was William Pitt the Younger, who led the Tory Party to victory in the 1784 general election when aged 25. In recent years, the youngest prime minister to be on the winning side at a general election was David Cameron, who was 43 years and 209 days old when he led the Conservative Party to victory as the largest party in the 2010 general election.

William Ewart Gladstone, was the oldest. He was 82 years of age when he returned to office after his Liberal Party was successful in the 1892 general election. The oldest prime minister to be victorious at a general election for the first time was Winston Churchill, who was 75 years of age when his Conservative Party won the 1951 general election.

In office without a general election

[edit]

15 former prime ministers never fought a general election while they held office (or to gain office), usually by serving terms sandwiched between the victors of elections and the prime ministers who faced the next elections. Chronologically they were:

- Lord Wilmington

- The Duke of Devonshire

- Lord Bute

- George Grenville

- The Duke of Grafton

- Lord Rockingham (served both his terms election-less)

- Lord Shelburne

- Spencer Perceval

- George Canning

- Lord Goderich

- Lord Aberdeen

- Lord Rosebery

- Arthur Balfour[note 1]

- Neville Chamberlain

- Liz Truss

PMs who served from (or later entered) the House of Lords

[edit]John Russell was unique in serving one entire term at Downing Street as Commons MP, when known as Lord John Russell (as younger son of a Duke of Bedford) in 1846–1852, and his second and last entirely as a member of the Lords as the 1st Earl Russell in 1865–1866, having been raised to the peerage between terms in 1861.

Without counting Lord Russell, eighteen prime ministers served their entire terms from the House of Lords where they were already members. In the following chronological list, those PMs who never served in the House of Commons during their political career are marked with an asterisk (*):

- Lord Wilmington

- The Duke of Newcastle *

- The Duke of Devonshire

- Lord Bute *

- Lord Rockingham *

- The Duke of Grafton

- Lord Shelburne (later Lord Lansdowne) *

- Duke of Portland

- Lord Grenville

- Lord Liverpool

- Lord Goderich (later Lord Ripon)

- The Duke of Wellington

- Lord Grey

- Lord Melbourne

- Lord Derby

- Lord Aberdeen *

- Lord Salisbury

- Lord Rosebery *

Three prime ministers were elevated from the Commons to the House of Lords during their terms through being raised to the peerage.

- Robert Walpole – created 1st Earl of Orford five days before formally resigning in 1742

- William Pitt the Elder – created 1st Earl of Chatham five days after taking office in 1766

- Benjamin Disraeli – created 1st Earl of Beaconsfield in 1876, two years after taking his second term of office in 1874

Lord North succeeded to his father's peerage as the 2nd Earl of Guilford in 1790 after being in office.

Alec Douglas-Home disclaimed his hereditary peerage as the 14th Earl of Home four days after coming to office in 1963 (under the Peerage Act of that year), giving up his seat in the Lords, and subsequently sat in the Commons after succeeding in a by-election, pending which for 20 days he held office from neither House. He returned to the Lords when made a life peer as Baron Home of the Hirsel in 1974.

Thirteen prime ministers have served their entire terms as Members of the House of Commons but were elevated to the House of Lords afterwards by being created peers.

- Henry Addington – became the 1st Viscount Sidmouth in 1805

- Arthur Balfour – became the 1st Earl of Balfour in 1922

- H. H. Asquith – became the 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith in 1925

- Stanley Baldwin – became the 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley in 1937

- David Lloyd George – became the 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor in 1945 (22 years after being prime minister, although he did not live to take his seat in the Lords)

- Clement Attlee – became the 1st Earl Attlee in 1955

- Anthony Eden – became the 1st Earl of Avon in 1961

- Harold Wilson – became Baron Wilson of Rievaulx in 1983 (life peer)

- Harold Macmillan – became the 1st Earl of Stockton in 1984

- James Callaghan – became Baron Callaghan of Cardiff in 1987 (life peer)

- Margaret Thatcher – became Baroness Thatcher in 1992 (life peer)

- David Cameron – became Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton in 2023 (life peer)

- Theresa May – became Baroness May of Maidenhead in 2024 (life peer)

In contrast, 18 prime ministers preceding the current (Keir Starmer) have never become members of the House of Lords, including six of his eight immediate predecessors. Henry Pelham (served 1743 to his death in 1754) was the first to be a lifelong "Commoner". (The convention of prime ministers leading from the House of Commons only became established in the 20th century.)

Holders of Irish peerages (with the exception of 28 Irish representative peers allowed after 1801, who were elected from among their peers) legally did not sit in the House of Lords in the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom, but were allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Lord Palmerston was the only Irish peer to serve as prime minister, thus leading from the House of Commons.

Service in House of Commons

[edit]

The shortest period between entering Parliament and being appointed prime minister was achieved by William Pitt the Younger who became prime minister two years after first becoming an MP. The longest period of service as an MP before becoming prime minister was 47 years for Lord Palmerston.

The oldest debut of a future prime minister as MP was by Keir Starmer who was elected, aged 52 years 247 days, at general election in 2015.

The youngest at first election was Augustus FitzRoy, Earl of Euston (later the Duke of Grafton), who was elected on 10 December 1756 aged 21 years and 73 days. He also had the shortest period as an MP enjoyed by a prime minister, nearly five months, representing two successive seats (the first of which he only held for 11 days before being elected for his second) until going to the House of Lords when he succeeded his father as the 3rd Duke of Grafton on 6 May 1757, eleven years before his term of office began.

Winston Churchill served the longest as MP, for a total of 63 years and 360 days, for five successive seats, between 1 October 1900 and retirement on 25 September 1964, excluding two intervals out of parliament (in 1908 and in 1922–1924). He retired as Father of the House. He was in the Commons throughout both his terms as prime minister, and his service covered the terms of eleven other prime ministers, from Lord Salisbury (second ministry) to Alec Douglas-Home, but did not serve under Bonar Law who was in office when Churchill was briefly out of parliament.

David Lloyd George had the longest unbroken career as an MP, for one seat, Carnarvon Boroughs, from a by-election on 10 April 1890 until his death on 26 March 1945, a period of 54 years and 350 days. He received a peerage on 1 January 1945 but was not able to take his seat in the Lords. From 1929 he had been Father of the House. His career as an MP covered the terms of eleven other prime ministers, from Lord Salisbury (first ministry) to Winston Churchill (first ministry).

Alec Douglas-Home had the longest interval between terms of service in the Commons. He automatically vacated his Commons seat at Lanark on 11 July 1951 by succeeding his father and going to the House of Lords as the 14th Earl of Home. He gained his next Commons seat at Kinross and Western Perthshire in a by-election on 7 November 1963, after becoming prime minister and disclaiming his hereditary peerage. The interval between these terms as MP was 12 years and 123 days. He had a previous interval out of the Commons between defeat in the 1945 general election and returning in that of 1950 over four years later.

No parliamentary constituency has been represented by more than one serving prime minister. Four future prime ministers sat for Newport, Isle of Wight (constituency abolished 1832): Lord Palmerston and Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington) in 1807–1809, George Canning in 1826–1827 and William Lamb, later Lord Melbourne in April–May 1827.

It is rare for veteran prime ministers sitting in the Commons to lose seats through electoral defeat at subsequent general elections. Those who have are:

- Arthur Balfour (Manchester East) in 1906

- H. H. Asquith (East Fife) in 1918

- Ramsay MacDonald (Seaham) in 1935

- Liz Truss (South West Norfolk) in 2024

PMs who were Fathers of the House

[edit]Five prime ministers through longest unbroken service became Father of the House. Henry Campbell-Bannerman was the first prime minister to achieve this status, uniquely while in office, in 1907. He was still serving as an MP when he died shortly after retiring as prime minister. The others listed in the table below became Father after the end of their terms. James Callaghan became Father only 4 years and 36 days after the end of his term in office, while at the other extreme Edward Heath became Father 18 years after the end of his.

| Name | Entered House | Tenure as PM | Became Father | Left House | Party | Constituency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry Campbell-Bannerman | 1868 | 1905–1908 | 1907 | 1908 (died) | Liberal | Stirling Burghs | |

| David Lloyd George | 1890 | 1916–1922 | 1929 | 1945 | Liberal | Caernarvon Boroughs | |

| Winston Churchill | 1900 |

|

1959 | 1964 | Conservative |

| |

| James Callaghan | 1945 | 1976–1979 | 1983 | 1987 | Labour | Cardiff South and Penarth | |

| Edward Heath | 1950 | 1970–1974 | 1992 | 2001 | Conservative | Old Bexley and Sidcup | |

Number of living former PMs

[edit]None

[edit]Four prime ministers have been in office at a time when no former prime ministers were alive.

- Robert Walpole – As the first prime minister, for his entire term, April 1721 to February 1742.

- Henry Pelham – From the death of Robert Walpole in March 1745, until his own death in March 1754.

- The Duke of Newcastle – For his entire first term, June 1754 to May 1756.

- William Ewart Gladstone – From the death of Benjamin Disraeli in April 1881 until the end of his second term in June 1885.

One

[edit]Twelve prime ministers have been in office at times when only one former prime minister has been alive at or for each time.

- Lord Wilmington – From his appointment in February 1742 until his death in July 1743, only Robert Walpole was alive.

- Henry Pelham – From his appointment in August 1743 until the death of Robert Walpole, in March 1745, only Walpole was alive.

- The Duke of Newcastle – In his second term, July 1757 to May 1762, only the Duke of Devonshire was alive.

- The Duke of Devonshire – In his term, November 1756 to June 1757, only the Duke of Newcastle was alive.

- Lord Russell – In his second term, October 1865 to June 1866, only Lord Derby was alive.

- Lord Derby – In his third term, June 1866 to February 1868, only Lord Russell was alive.

- Benjamin Disraeli – From the death of Lord Russell in May 1878 until the end of his second term in April 1880, only Gladstone was alive.

- William Ewart Gladstone – From his second appointment in April 1880 until the death of Benjamin Disraeli, in April 1881, only Disraeli was alive. In his third term, February 1886 to July 1886, and in his fourth term, August 1892 to March 1894, only Lord Salisbury was alive.

- Lord Salisbury – In his first term, June 1885 to January 1886, and in his second term, July 1886 to August 1892, only Gladstone was alive. In his third term, from the death of Gladstone until the end of the term, May 1898 to July 1902, only Lord Rosebery was alive.

- Arthur Balfour – From the death of Lord Salisbury in August 1903 until the end of his term in December 1905, only Lord Rosebery was alive.

- Winston Churchill – In his second term, October 1951 to April 1955, only Clement Attlee was alive.

- Clement Attlee – From the death of Stanley Baldwin in November 1947 until the end of his term in October 1951, only Winston Churchill was alive.

Most

[edit]Following Labour's victory at the 2024 general election, there are currently eight living former prime ministers, which is the record for the number of living former prime ministers at any time. From oldest to youngest:

| Name | Date of birth | Tenure |

|---|---|---|

| Sir John Major | 29 March 1943 | 1990–1997 |

| Gordon Brown | 20 February 1951 | 2007–2010 |

| Sir Tony Blair | 6 May 1953 | 1997–2007 |

| Theresa May | 1 October 1956 | 2016–2019 |

| Boris Johnson | 19 June 1964 | 2019–2022 |

| David Cameron | 9 October 1966 | 2010–2016 |

| Liz Truss | 26 July 1975 | 2022 |

| Rishi Sunak | 12 May 1980 | 2022–2024 |

Sunak is still a serving member of the House of Commons.

The most recent death of a former prime minister was that of Margaret Thatcher (served 1979–1990) on 8 April 2013 (aged 87).

In the House of Commons

[edit]The record for most prime ministers (current or former) to be members of the House of Commons at the same time is four: a sitting prime minister and three former prime ministers. This has occurred on five separate occasions:

| Prime minister | Former prime ministers | From | To | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanley Baldwin | Asquith, Lloyd George, Law | 20 May 1923 | 30 October 1923 | 163 days |

| Ramsay MacDonald | Asquith, Lloyd George, Baldwin | 22 January 1924 | 9 October 1924 | 261 days |

| Neville Chamberlain | Lloyd George, MacDonald, Baldwin | 28 May 1937 | 30 June 1937 | 33 days |

| Margaret Thatcher | Heath, Wilson, Callaghan | 4 May 1979 | 13 May 1983 | 4 years 9 days |

| Rishi Sunak | May, Johnson, Truss | 25 October 2022 | 9 June 2023 | 8 months 14 days |

The fewest former prime ministers still sitting in the House of Commons is zero, which has happened on a number of occasions, most recently between 12 September 2016 when David Cameron left Parliament and 24 July 2019 when Theresa May left office.

Died in office

[edit]

Seven prime ministers have died in office:

- Lord Wilmington – died on 2 July 1743, aged 70

- Henry Pelham – died on 6 March 1754, aged 59

- Lord Rockingham – died on 1 July 1782, aged 52

- William Pitt the Younger – died on 23 January 1806, aged 46; the youngest to die in office

- Spencer Perceval – was assassinated by John Bellingham on 11 May 1812, aged 49

- George Canning – died on 8 August 1827, aged 57

- Lord Palmerston – died on 18 October 1865, aged 80 (two days before his 81st birthday); the oldest to die in office

Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Bonar Law each resigned during their respective final illnesses. Law died five months after his resignation, but Campbell-Bannerman lived only another 19 days, dying at 10 Downing Street, the only prime minister ever to do so.

Others who died within one year of the end of their term were the Duke of Portland who died in 1809, 26 days after he left office, and Neville Chamberlain, who died in 1940, 183 days after he left office, of a cancer that was undiagnosed at the time of his resignation.

Assassination and attempts

[edit]Spencer Perceval is the only British prime minister to have been assassinated.

Lord Liverpool, Robert Peel, Margaret Thatcher, and John Major survived targeted assassination attempts in 1820, 1843, 1984, and 1991 respectively while in office, while Edward Heath survived one in 1974 after he had been ousted from office.[2]

Died while immediate successors were in office

[edit]Nine former prime ministers have died while their immediate successors were in office:

- The Duke of Portland – died during Spencer Perceval's term

- Robert Peel – died during Lord John Russell's first term

- Lord Aberdeen – died during Lord Palmerston's second term

- Benjamin Disraeli – died during William Ewart Gladstone's second term

- William Ewart Gladstone – died during Lord Salisbury's third term

- Lord Salisbury – died during Arthur Balfour's term

- Henry Campbell-Bannerman – died during H. H. Asquith's term

- Bonar Law – died during Stanley Baldwin's first term

- Neville Chamberlain – died during Winston Churchill's first term

All of the above-listed prime ministers were older than their immediate successors. The Duke of Portland and Lord Aberdeen are the only ones among this list whose immediate successors also died in office.

Armed forces veterans

[edit]

The earliest prime minister to be an armed forces veteran was Henry Pelham (1743–1754), who had served as a volunteer soldier in James Dormer's Regiment of Dragoons during the Jacobite rising of 1715 and fought at the Battle of Preston that year against the Jacobite forces.

The most recent prime minister to be an armed forces veteran was James Callaghan (1976–1979), who served in the Royal Navy in the Second World War, from 1942 to 1945, seeing action with the East Indies Fleet and reaching the rank of Lieutenant. He was the only future prime minister to serve in the navy rather than the army.

In contrast to many nations, Britain has had only two prime ministers who have been military generals: Lord Shelburne (1782–1783), who was promoted from Lieutenant-General to full General in the British Army in the latter year, and the Duke of Wellington, who achieved the supreme rank of Field Marshal in 1813. He was prime minister twice, in 1828–1830 and 1834, in the interval between his two terms as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces. During his military career he took part in some 60 battles, seeing more wartime combat than any other future prime minister.

No future prime ministers have yet served in the flying services, although Neville Chamberlain (1937–1940) and Winston Churchill (1940–1945 and 1951–1955) were honorary Air Commodores in the Auxiliary Air Force during their respective terms of office.

Active members of the regular armed forces are disqualified for membership of the House of Commons at least since 1975.[3]

Active service veterans

[edit]Jacobite Rising (1715)

[edit]- Henry Pelham – Dormer's Regiment – fought in the Battle of Preston

Jacobite Rising (1745)

[edit]- Lord Rockingham – Colonel of volunteers raised against invasion from Scotland

Seven Years' War

[edit]- Lord Shelburne – Colonel, 20th Foot – Canada, France, Germany

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

[edit]- The Duke of Wellington – Field Marshal, Army – Flanders, India, Peninsular War, and Waterloo Campaign

In addition, the following served in home-based militia, volunteer, or yeomanry units raised during the same wars, but were not deployed abroad:

- William Pitt the Younger – Colonel of volunteers (he was serving when he died in office in 1806)

- Lord Grenville – Major of yeomanry, Lieutenant-Colonel of volunteers

- Henry Addington – Captain of volunteers

- Spencer Perceval – Volunteer, London and Westminster Light Horse

- Lord Liverpool – Colonel of fencible cavalry, later of militia

- Lord Goderich – Major of yeomanry

- Robert Peel – Captain of militia

- Lord Melbourne – Major of volunteer infantry

- Lord Palmerston – Captain of volunteers, Lieutenant-Colonel of militia

- Lord Russell – Captain of militia

Mahdist War

[edit]- Winston Churchill – Lieutenant, 4th Queen's Own Hussars, attached 21st Lancers

Second Boer War

[edit]- Winston Churchill – Lieutenant, South African Light Horse and war correspondent (prisoner of war)

World War I

[edit]- Winston Churchill – Major, Grenadier Guards, later Lieutenant-Colonel, Royal Scots Fusiliers – Western Front

- Clement Attlee – Major, South Lancashire Regiment – Gallipoli Campaign, Mesopotamian campaign and Western Front (wounded)

- Anthony Eden – Major, Rifle Brigade – Western Front

- Harold Macmillan – Captain, Grenadier Guards – Western Front (wounded)

World War II

[edit]- Edward Heath – Lieutenant-Colonel, Royal Artillery – North West Europe

- James Callaghan – Lieutenant, Royal Navy – East Indies

Although Eden and Alec Douglas-Home were Territorial Army officers at outbreak of war in 1939, neither was mobilised and the latter was invalided due to disabling spinal tuberculosis.

War-bereaved

[edit]The following lost close relations in their lifetimes as a result of war:

- Lord Rosebery – one son killed in action in the First World War

- H. H. Asquith – one son killed in action in the First World War (during his period in office)

- Bonar Law – two sons killed in action in the First World War

- Anthony Eden – two brothers killed in action in the First World War, and one son killed in action in the Second World War

- Alec Douglas-Home – one brother killed on active service in the Second World War

Also:

- Lord Bute – one male line grandson (born in his lifetime) died serving aboard ship in the Napoleonic War

- Robert Peel – one surviving son died serving in the Indian Rebellion of 1857

- William Ewart Gladstone – two male line grandsons (born in his lifetime) were killed in action in the First World War

- Lord Salisbury – four male line grandsons (born in his lifetime) were killed in action in the First World War

Decorated

[edit]

The most decorated British prime minister was Winston Churchill, KG, OM, CH, TD, who received a total of 38 orders, decorations and medals,[note 2] from the United Kingdom and thirteen other states (on continents of Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America). Ten were awarded for active service as an Army officer in Cuba, India, Egypt, South Africa, the United Kingdom, France, and Belgium. The greater number of awards were given in recognition of his service as a minister of the British government.[4][note 3]

Churchill was also the only British prime minister to have received a Nobel Prize (for Literature, in 1953).

The most widely decorated prime minister by the number of states from which he received honours was the Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, who is known to have received 28 orders, decorations and medals from the United Kingdom and seventeen other states (all in Europe), in recognition of his military services.

The British order of knighthood most frequently conferred on prime ministers has been the Order of the Garter, of which 30 male prime ministers (beginning with Sir Robert Walpole and later including Sir Winston Churchill and Sir Anthony Eden) have been Knights Companion (KG), and the first female, Margaret Thatcher, a Lady Companion (LG) of the Order. Nine prime ministers, including Thatcher, received it after serving office. Currently, the only living knights among them are Sir John Major, knighted in 2005, and Sir Tony Blair, knighted in the 2022 New Year Honours. Current Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer is a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, having been knighted in 2014 before entering office.

The only prime minister to have received a British gallantry award was Anthony Eden, who won the Military Cross (MC) while serving in the army in the First World War, before entering parliament.[5][6]

Family

[edit]Married

[edit]

The longest-married prime minister was James Callaghan, who was married to his wife Audrey for 66 years from 28 July 1938 until her death on 15 March 2005.

Four prime ministers married while in office, three not being their first marriage:

- Robert Walpole to Maria Skerrett before 3 March 1738. She died after a miscarriage on 4 June that year, after at least 93 days' marriage, making this the shortest marriage ever held by a prime minister (although she previously cohabited as his mistress).

- The Duke of Grafton to Elizabeth Wrottesley on 24 June 1769. She survived him, dying in 1822.

- Lord Liverpool to Lady Mary Chester on 24 September 1822. She survived him.

- Boris Johnson married Carrie Symonds, his third wife, on 29 May 2021. He divorced both his first wife, Allegra Mostyn-Owen, and his second, Marina Wheeler.

Widowed

[edit]Widowed the longest

[edit]The British prime minister widowed the longest is Lord Rosebery who died more than 38 years after his wife.

Recently, the British prime minister widowed the longest is Harold Macmillan, who was widowed from 21 May 1966 to his death on 29 December 1986, a total of 20 years.

Widowed the shortest

[edit]The British prime minister widowed the shortest is James Callaghan, who died on 26 March 2005. His wife, Audrey Callaghan, died on 15 March 2005, only 11 days before him.

Other widowed

[edit]- Robert Walpole (twice widowed, when in office: 1737 and 1738)

- The Duke of Devonshire

- George Grenville

- Lord Shelburne (twice widowed)

- Henry Addington

- Lord Liverpool (widowed when in office: 1821; remarried)

- The Duke of Wellington

- Lord Melbourne

- Lord Russell (remarried)

- Lord Aberdeen (twice widowed)

- Benjamin Disraeli

- Lord Salisbury (when in office: 1899)

- Henry Campbell-Bannerman (widowed when in office: 1906)

- H. H. Asquith (remarried)

- David Lloyd George (remarried)

- Bonar Law

- Stanley Baldwin

- Ramsay MacDonald

- Clement Attlee

- Alec Douglas-Home

- Margaret Thatcher

Divorced

[edit]Three British prime ministers have been divorced.

- The Duke of Grafton divorced his first wife, Anne (née Liddell), by Act of Parliament passed 23 March 1769, during his term of office, then remarried on 24 June that year to Elizabeth Wrottesley. (Anne remarried on 26 March 1769 to John FitzPatrick, 2nd Earl of Upper Ossory and died in 1804 in Grafton's lifetime.)

- Anthony Eden, divorced his first wife Beatrice (née Beckett) in 1950, then remarried two years later to Clarissa Spencer-Churchill on 14 August 1952, before his term of office began. (Beatrice never remarried and died in 1957 in Eden's lifetime.)

- Boris Johnson divorced his first wife Allegra Mostyn-Owen in 1993 and married Marina Wheeler two weeks later. In 2018, Johnson and Wheeler separated, finalising their divorce in November 2020 during Johnson's term of office.

Bachelors

[edit]Four British prime ministers have been bachelors.

Most children

[edit]The most prolific prime minister was apparently Lord Grey who in wedlock fathered ten sons and six daughters[7] in addition to one illegitimate daughter by Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire who was subsequently raised by Grey's parents.[8]

Had children in office

[edit]Four prime ministers are known to have fathered children while in office: Lord John Russell (two sons, George (1848) and Francis (1849)), Tony Blair (one son, Leo (2000)), David Cameron (one daughter, Florence (2010)) and Boris Johnson (one son, Wilfred (2020) and one daughter, Romy (2021)).[9]

Russell and Johnson also have the rare distinction of fathering further children after leaving Downing Street.[10] David Lloyd George possibly had a daughter with his mistress Frances Stevenson after leaving office, but the historical consensus is that it is unlikely that he was her father.[11]

No female prime minister has ever given birth in office.

Kindred PMs

[edit]At least 24 British prime ministers were related to at least one other prime minister by blood or marriage.

Fathers and sons

[edit]Two sets of father and son have successively held the office:

- Lord Chatham (aka "Pitt the Elder") and William Pitt the Younger

- George Grenville and William, Lord Grenville

Brothers

[edit]- The only brothers to hold the office were Henry Pelham (PM 1743–1754) and his older brother and immediate successor Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle (PM 1754–1756, 1757–1762).

Full cousins

[edit]- Pitt the Younger and Lord Grenville (who directly succeeded the former in office) were the only set of full cousins to hold the office, their fathers being brothers-in-law.

Uncles and nephews

[edit]There have been two blood uncle-nephew sets of prime ministers.

- George Grenville and William Pitt the Younger

- Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury and Arthur Balfour, who succeeded Salisbury in office after the latter's last term. The phrase "Bob's your uncle" is said to have originated in connection with this set, from ministerial promotions Balfour gained under Salisbury.[12][13]

Great-great-uncle and great-great-nephew

[edit]- Lord Wilmington was two-greats uncle of Spencer Perceval, whose mother, Catherine (née Compton), Baroness Arden, was a blood great-niece of Wilmington.

Father-in-law and son-in-law

[edit]- The Duke of Portland, married in 1766 Lady Dorothy Cavendish, daughter of the Duke of Devonshire (who had died in 1764).

Brothers-in-law

[edit]- Pitt the Elder was married from 1754 to George Grenville's sister Hester.

- Lord Palmerston was married from 1839 to Lord Melbourne's sister Emily, dowager Countess Cowper.

Uncles-in-law and nephews-in-law

[edit]- William Pitt the Elder married Hester Grenville who was the sister of George Grenville and the aunt of William Grenville, which makes William Pitt the Elder the uncle-in-law of William Grenville.

- Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden. In 1952, during Churchill's second term, Eden married Clarissa, daughter of John Strange Spencer-Churchill, Winston's brother, before succeeding to the office.

Great-uncle-in-law and great-nephew-in-law

[edit]- Lord Grenville was married from 1792 to Anne Pitt, daughter of Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford who was a nephew of William Pitt the Elder.

Great-great-great-grandfather and great-great-great-grandson

[edit]- Alec Douglas-Home was the great-great-great-grandson of Lord Grey.

Great-great-great-uncle and great-great-great-nephew

[edit]Great-great-great-grandfather-in-law and great-great-great-grandson-in-law

[edit]- Harold Macmillan was married from 1920 until 1966 to Dorothy Cavendish, who was a great-great-great-granddaughter of the Duke of Devonshire.

Education

[edit]

| Record | Institution | Number of PMs | First and most recent | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School with most alumni prime ministers | Eton College | 20 | Robert Walpole to Boris Johnson | Harrow School has educated 7 prime ministers, most recently Winston Churchill |

| University with most alumni prime ministers | Oxford University | 31 | Lord Wilmington to Keir Starmer | Cambridge University has educated 14 prime ministers, most recently Stanley Baldwin |

| University college with most alumni prime ministers | Christ Church, Oxford | 13 | George Grenville to Alec Douglas-Home | |

| Vocational institution with most prime ministers as students | The Inns of Court | 12 | Lord Wilmington to Keir Starmer | Of these, eight passed through Lincoln's Inn (William Pitt the Younger to Tony Blair) |

The most popular degree course with future prime ministers is Classics, read by 7 PMs (Robert Peel to Boris Johnson). Six prime ministers read PPE (Harold Wilson to Rishi Sunak).

The first prime minister never to have been a university graduate was the Duke of Devonshire (served 1756–1757); the most recent is John Major (served 1990–1997).

Languages and multilingualism

[edit]One British prime minister did not speak English as a first language – David Lloyd George, who was raised in a Welsh-speaking family.

Many prime ministers have understood Latin and/or Ancient Greek, which were traditionally taught as part of a classics education. The most recent prime minister noted to have studied these languages is Boris Johnson.

Until the early 20th century, French was the primary language of diplomacy, and most prime ministers until this time had at least some understanding of it. Benjamin Disraeli was notable for being unable to speak the language and addressing diplomatic conferences in English.[14]

Prime ministers who have been specifically noted as speaking languages other than English include:

- Winston Churchill, who spoke some French.[15]

- Anthony Eden, who spoke Arabic, French, German, Persian and some Turkish.[16]

- Tony Blair, who speaks French.[17]

- Boris Johnson, who as well as Latin and Ancient Greek speaks some French, German, Italian and Spanish.[18]

- Rishi Sunak, who speaks some Hindi and Punjabi.[19]

Wealth

[edit]After being appointed prime minister by King Charles III on 25 October 2022, Rishi Sunak became one of the wealthiest prime ministers ever, with an estimated combined fortune with his wife of £730 million.[20]

The richest prime minister was Lord Derby, with a personal fortune of over £7 million, equivalent to £871 million in 2023.[21]

The poorest prime minister was William Pitt the Younger, who was £40,000 (now over £4 million) in debt by 1800.[22][23]

Legal issues

[edit]Before becoming prime minister, Robert Walpole was impeached and convicted in 1712 for "a high breach of trust and notorious corruption" and sentenced to six months imprisonment in the Tower of London.[24]

In 2006 and 2007, Tony Blair became the first sitting prime minister to be questioned as part of a criminal investigation, following the Cash-for-Honours scandal, but this was not under caution.[25][26]

In 2022, Boris Johnson received a fixed-penalty notice relating to violations of the COVID-19 lockdown regulations in the Partygate scandal, becoming the first prime minister found to have broken the law in office. Future prime minister Rishi Sunak, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, was also fined at the same time.[27]

In January 2023, during his period in office, Rishi Sunak was issued a fixed penalty notice by Lancashire Police for failing to wear a seatbelt in his ministerial car while filming an Instagram video to promote his government's levelling up policy.[28] Sunak hence became the second prime minister in history to be found to have broken the law in office.[29]

Female

[edit]

There have been three female prime ministers, all Conservative. They have led the United Kingdom for a total of 14 years, 268 days.

- Margaret Thatcher – served May 1979 – November 1990, 11 years, 208 days.

- Theresa May – served July 2016 – July 2019, 3 years, 11 days.

- Liz Truss – served September–October 2022, 49 days.

Between Cameron's appointment in 2010 and Sunak's resignation in 2024, male and female Prime Ministers alternated.

Birthplace

[edit]Two prime ministers were born in Ireland, both in Dublin in the Kingdom of Ireland before the Act of Union 1801.

- Lord Shelburne – born in Dublin in 1737

- The Duke of Wellington – born at 6 Merrion Street, Dublin, in 1769

Two further prime ministers were born outside of the British Isles.

- Bonar Law – born in the colony of New Brunswick in what is now Canada, the first prime minister born outside the British Isles

- Boris Johnson – born in New York City in the United States, the first American-born prime minister and the first to be born outside English/British territory

All other prime ministers were born in Great Britain (46 in England and 7 in Scotland). Although of Welsh origin, David Lloyd George was born in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire.

Nationality and ethnicity

[edit]The English are a majority within the United Kingdom. Several prime ministers have come from the other nations of the United Kingdom.

Irish

[edit]Most of the Irish prime ministers were of Anglo-Irish background, largely descended from Protestant English settlers rather than the Gaelic Irish. However, James Callaghan's grandfather had an Irish Catholic background.[30]

- Lord Shelburne (served 1782–1783)

- George Canning (served 1827) – born in England to Irish parents, represented English constituencies, except for a brief period as MP for Tralee in 1802–1806

- The Duke of Wellington (served 1828–1830)

- Lord Palmerston (served 1855–1858 and 1859–1865) – born in England to an Anglo-Irish noble family, represented an English constituency

- James Callaghan (served 1976–1979)

Scottish

[edit]- Lord Bute (served 1762–1763)

- Lord Aberdeen (served 1852–1855)

- William Ewart Gladstone (served 1868–1874, 1880–1885, 1886, and 1892–1894) – born in England to Scottish parents, represented a Scottish constituency (Midlothian) for his final three terms in office

- Lord Rosebery (served 1894–1895) – born in England to a family of Scottish nobility

- Arthur Balfour (served 1902–1905)

- Henry Campbell-Bannerman (served 1905–1908)

- Bonar Law (served 1922–1923) – born in Canada to parents of Scottish ancestry, lived in Scotland from a young age, sat for a Scottish constituency during his term in office

- Ramsay MacDonald (served 1924 and 1929–1935)

- Harold Macmillan (served 1956–1963) – though born and lived lifelong in England, his paternal grandfather was Scottish and Macmillan considered himself a Scot[31]

- Alec Douglas-Home (served 1963–1964) – born in England to a family of Scottish nobility, lived in Scotland, where he sat for constituencies, in adulthood

- Tony Blair (served 1997–2007) – born in Scotland, and went to school there, but subsequently lived in England

- Gordon Brown (served 2007–2010)

- David Cameron (served 2010–2016) – born in England to a family of part Scottish ancestry, his great-great-grandfather Sir Ewan Cameron was born in Inverness-shire, and he is descended from the Chiefs of Clan Cameron of Lochiel

Welsh

[edit]- David Lloyd George (served 1916–1922) – born in England of Welsh parents and Welsh-speaking, only prime minister from a non-English-speaking background. Sat for a Welsh constituency.

American

[edit]- Boris Johnson, first American-born prime minister (born in New York City). Also first British prime minister to have been potentially eligible for the office of President of the United States: until 2016 he was a natural-born citizen, but had not completed the required 14 years of US residence. He has both Muslim (Turkish and Circassian) and (Russian-Lithuanian) Jewish ancestry, one ancestor having been a rabbi and a great-grandfather having been the journalist and politician Ali Kemal.

Canadian

[edit]- Bonar Law, first Canadian-born prime minister (born in Kingston, Colony of New Brunswick, now Rexton, New Brunswick, Canada)

British Jewry

[edit]- Benjamin Disraeli was of Jewish descent, though his ancestors had lived in other European countries.[32][33][34] His grandfather migrated to England from Italy in 1748.[35]

Anglo-Indian

[edit]- Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool was descended from Portuguese settlers in India; he may also have been one-sixteenth Indian in ancestry.[36][37][38][39]

British Indian

[edit]- Rishi Sunak is the first prime minister of British Asian and British Indian descent, as well as the first person of colour to be prime minister.[40][41] He was born in England to African-born Hindu parents of Indian Punjabi descent. His parents were both born in the Indian diaspora in Southeast Africa, his father in the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya (present-day Kenya) and his mother in Tanganyika Territory (now part of Tanzania).

Religious background

[edit]Christian

[edit]Britain's prime ministers have been predominantly Church of England by denomination, in an office which has had input into the appointment of that Church's bishops. The first to hold the office from outside the Church of England was Lord Bute, who was a member of the Scottish Episcopal Church, while the Duke of Grafton was the first to convert away by formally becoming a Unitarian, after leaving office. Prime ministers of other denominations (when in office, unless otherwise stated) were:

Church of Scotland

[edit]

Scottish Episcopal Church

[edit]Unitarian Church

[edit]- The Duke of Grafton – Church of England when in office, became member of Unitarian congregation in London in 1774.[42]

- Ramsay Macdonald – a Unitarian between leaving his native Free Church of Scotland and joining the Ethical Union.

- Neville Chamberlain – raised in a Unitarian family, but, apart from funerals, was not shown to have attended religious services during his adult life and showed no interest in organised religion.[43]

Congregationalist Church

[edit]Baptist Church

[edit]- David Lloyd George – lost his faith as a youth, but retained an appreciation of good preaching and hymn-singing.[44][45]

- James Callaghan – became atheist by the time he reached office.[46]

Free Church of Scotland

[edit]- Bonar Law

- Ramsay MacDonald – became a Unitarian and then joined the Ethical Union

Methodist Church

[edit]- Margaret Thatcher – until 1951; Anglican subsequently and while in office

Roman Catholic Church

[edit]- Tony Blair – Anglican while in office, he was married to a Catholic and converted to Catholicism after leaving office in 2007

- Boris Johnson – baptised as a Roman Catholic but became an Anglican while at school. On 29 May 2021, he married Carrie Symonds, a Catholic, at Westminster Cathedral, a Catholic church.[47]

Other religions

[edit]Judaism

[edit]

- Benjamin Disraeli – until 1817; Anglican subsequently and while in office

Hinduism

[edit]- Rishi Sunak – on 25 October 2022 became the first Hindu to be prime minister. As chancellor of the exchequer in 2021, he noted leaving lighted Diwali candles on the steps of 11 Downing Street as one of his proudest achievements and also has a history of taking his oath of office with a copy of the Bhagavad Gita.[48] He is also the first religious prime minister to follow a religion which is not Christianity upon taking office.[49]

Non-religious

[edit]- David Lloyd George – lost his faith as a youth, but retained an appreciation of good preaching and hymn-singing[44][45]

- Neville Chamberlain – described himself as "reverent agnostic", despite still holding some sympathies for the Unitarian principles he was raised in[43]

- Winston Churchill – wrote that he "[did] not accept the Christian or any other form of religious belief". Was strongly anti-religious in his early years and agnostic for the rest of his life, supporting the established Anglican church "from the outside".[50]

- Clement Attlee – an agnostic who described himself as "incapable of religious feeling", saying that he believed in "the ethics of Christianity" but not "the mumbo-jumbo"[51]

- James Callaghan – became an atheist while working as a trade union official[46]

- Liz Truss – described herself as "[sharing] the values of the Christian faith and the Church of England, but I'm not a regular practising religious person."[52]

- Keir Starmer – an atheist who chose to take a "solemn affirmation" (rather than an oath) of allegiance to the monarch.[53] He and his Jewish wife and children occasionally attend a liberal synagogue.[54]

Physical characteristics and disability

[edit]Height

[edit]The tallest prime minister is believed to be Lord Salisbury, who was around 6 feet 4 inches (193.0 cm) in height,[55] although Downing Street's own website lists 6-foot-1-inch (185.4 cm) James Callaghan as the tallest.[56]

The shortest prime minister to take office was believed to be Spencer Perceval who stood at around 5 feet 3 inches (160.0 cm) in height,[55] becoming nicknamed "Little P." for his stature.[57] When prime minister Liz Truss took office on 6 September 2022, she drew equal with this record, being also 5 feet 3 inches in height.[58] The next smallest prime ministers were Lord John Russell, who remained "under" 5 feet 5 inches (165.1 cm) throughout his adult life,[59] and Margaret Thatcher, who was 5 feet 5 inches (165.1 cm).[60]

Facial hair

[edit]British male prime ministers, when in office, have been predominately clean-shaven men, except for the following (as borne out by pictures):

Bearded

[edit]- Benjamin Disraeli (goatee) (served 1868 and 1874–1880)

- Lord Salisbury (only prime minister to wear a full-set beard; served 1885–1886, 1886–1892, 1895–1902)

Moustached

[edit]- Arthur Balfour (served 1902–1905)

- Henry Campbell-Bannerman (served 1905–1908)

- David Lloyd George (served 1916–1922)

- Bonar Law (served 1922–1923)

- Ramsay MacDonald (served 1924 and 1929–1935)

- Neville Chamberlain (served 1937–1940)

- Clement Attlee (served 1945–1951)

- Anthony Eden (served 1955–1957)

- Harold Macmillan (served 1957–1963)

In a pattern similar to the bald–hairy rule in Russia, between 1922 and 1957 men with moustaches succeeded clean-shaven men as prime minister, and vice versa.

Side whiskers (sideburns)

[edit]- George Canning (served 1827)

- Lord Grey (served 1830–1834)

- Lord Melbourne (served 1834 and 1835–1841)

- Lord John Russell (served 1846–1852 and 1865–1866)

- Lord Aberdeen (served 1852–1855)

- Lord Palmerston (served 1855–1858 and 1859–1865)

- Lord Derby (served 1852, 1858–1859 and 1866–1868)

- William Ewart Gladstone (served 1868–1874, 1880–1885, 1886, and 1892–1894)

Disability

[edit]At least seven prime ministers are known to have been physically disabled when in office.

- Lord Liverpool – incapacitated by a severe stroke on 17 February 1827,[61] forcing him to retire from office on 9 April 1827

- The Duke of Wellington – permanently deaf in his left ear after an operation intended to improve hearing in 1822

- William Ewart Gladstone – lost the forefinger of his left hand in an accident with a firearm in 1842. He also became partially blind by 1897, following his retirement from office.

- Winston Churchill – became increasingly deaf during his second term (condition onset in 1949) and had a series of strokes that led to his retirement and using a wheelchair in later years[62]

- Harold Macmillan – left with a slight limp and poor strength in his right hand, affecting his handwriting, after several wounds in the First World War.[63] He also became nearly blind later in his retirement.

- Gordon Brown – lost the sight of one eye in a school rugby accident at the age of 16[64]

- Theresa May – has diabetes

Others became disabled after leaving office, notably:

- The Duke of Newcastle – left lame and speech-impaired after a stroke in December 1767

- Lord North – lost his eyesight between 1786 and 1790

- John Russell, 1st Earl Russell – used a wheelchair in later life; his grandson Bertrand Russell recalled him as "a kindly old man in a wheelchair"[65]

- Lord Rosebery – movement, hearing, and eyesight increasingly impaired between a stroke in 1918 and his death in 1929

- Arthur Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour – became immobilised by phlebitis by 1929

- H. H. Asquith – became a wheelchair user by his last year (1928) following a stroke

- Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley – became deaf by October 1947, when he had to ask if a crowd cheering were booing him[66]

Harold Wilson is believed to have been aware he had early stage Alzheimer's disease when he resigned office in 1976, though he continued to serve as an MP until 1983.[67]

Prior to taking office, and while serving as an MP, Alec Douglas-Home was immobilised from 1940 to 1943 following an operation to treat spinal tuberculosis.

See also

[edit] Politics portal

Politics portal United Kingdom portal

United Kingdom portal- List of British monarchy records

- List of current heads of government in the United Kingdom and dependencies

- List of United Kingdom Parliament constituencies represented by sitting prime ministers

- Records of members of parliament of the United Kingdom

- Records of prime ministers of Australia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Balfour resigned on 4 December 1905 but was succeeded the next day by his then Liberal opponent, Campbell-Bannerman, who did not hold the next general election until January 1906. Balfour contested this as Leader of the Conservative Party and lost.

- ^ Medals in this context mean wearable awards, not including prize medals such as those accompanying the Nobel Prizes.

- ^ Before Churchill, the most decorated was the Duke of Wellington, whose orders, decorations and medals totalled at least 28.

References

[edit]- ^ "Sir Robert Walpole (Whig, 1721–1742) – History of government". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "History – The Year London Blew Up". Channel 4. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ "House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975: Section 1", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1975 c. 24 (s. 1)

- ^ "Orders, Decorations and Medals". The International Churchill Society. 18 June 2008.

- ^ "No. 30111". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1917. p. 5478.

- ^ "No. 13099". The Edinburgh Gazette. 4 June 1917. p. 1070.

- ^

Payne, Edward John (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 586–588, see page 588, third para, penultimate sentence.

By his wife Mary Elizabeth, only daughter of the first Lord Ponsonby, whom he married on the 18th of November 1794, he became the father of ten sons and five daughters.

- ^ Bolen, Cheryl. "Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire". Cheryl Bolen. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "All the babies who have been born at 10 Downing Street". Tatler. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "How many children does Boris Johnson have?", Independent, 11 July 2023

- ^ Hague, Ffion (2008). "New Loves". The Pain and the Privilege: The Women in Lloyd George's Life. London: Harper Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780007219490.

- ^ Trahair, R.C.S. (1994). From Aristotelian to Reaganomics: A Dictionary of Eponyms With Biographies in the Social Science. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-313-27961-4. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Bernstein, Jonathan (2006). Knickers in a Twist: A Dictionary of British Slang. Canongate U.S. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55584-794-4. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Watson, R. (1914). "Disraeli and French". The North American Review. 200 (708): 795–796. JSTOR 25108299.

- ^ "Churchill's French". International Churchill Society. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Aster, Sidney (1976). Anthony Eden. London: St Martin's Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-312-04235-6.

- ^ ""Parlez-vous Franglais, Prime Minister?"". BBC News. 24 March 1998. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Reading into the problem of illiteracy where 'Street' is often king". The Irish Times. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Next UK PM Rishi Sunak on being British, Indian and Hindu at the same time". Business Standard. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^

"Does Rishi Sunak's £730m fortune make him too rich to be PM?". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

Sunak and his wife, Akshata Murty, are sitting on a combined fortune of about £730m

- ^ "Richest British Prime Minister". guinnessworldrecords.com. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ "PITT, Hon. William (1759–1806), of Holwood and Walmer Castle, Kent". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "William Pitt the Younger". Regency History. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Hall of fame: Robert Walpole, Britain's first PM". The Gazette. HMSO. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Police quiz Blair inside Downing St on peerages". The Guardian. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Blair interviewed for second time". The Guardian. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "How much Boris Johnson was fined and what the law says about Covid fixed penalty notices". Daily Telegraph. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Rishi Sunak fined for not wearing seatbelt in back of car". BBC News. 20 January 2023.

- ^ Bruce, Andy; Suleiman, Farouq; Suleiman, Farouq (20 January 2023). "Sunak fined by police for failing to wear seat belt". Reuters.

- ^

Leonard, Dick (2005). James Callaghan — Labour's conservative. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 282–299. doi:10.1057/9780230511507_18. ISBN 978-1-4039-3990-6. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "PM Harold Macmillan - Wind of Change Speech at the Cape Town Parliament - 3 February 1960". YouTube. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Blake, Robert (1967). Disraeli. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-4039-3990-6.

- ^ Wolf, Lucien (1905). "The Disraeli Family". Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England. 5: 202–218.

- ^ Roth, Cecil (1952). Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield. Philosophical Library. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8022-1382-2.

- ^ Shachem, Daniela (18 September 2008). "The Disraeli Legacy". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Blake, Robert (18 October 1984). "Weathering the storm". London Review of Books. Vol. 6, no. 19. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Edward Croke's wife, Isabella Beizor (c. 1710–80), was a Portuguese Indian creole, thus giving Liverpool a trace (probably about one sixteenth, but maybe less) of Indian blood." Hutchinson, Martin, Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool

- ^

Brendon, Vyvyen (2015). Children of the Raj. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781780227474.

It is true that [Lord Liverpool's] maternal grandmother was a Calcutta-born woman, Frances Croke...there is no evidence that her half-Portuguese mother, Isabella Beizor, was Eurasian.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool was Not a Ninny". Shannon Selin. 10 January 2014.

- ^ Rao, Prashant (25 October 2022). "Rishi Sunak is the U.K.'s new Prime Minister. Who is he?". lA. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (24 October 2022). "Rishi Sunak to become first British PM of colour and also first Hindu at No 10". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 19. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 924. ISBN 0-19-861369-5.

- ^ a b Ruston, Alan. "Neville Chamberlain". Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b Crosby, Travis L. (2014). "The Education of a Statesman". The Unknown Lloyd George. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-78076-485-6.

- ^ a b Cregier, Don M. (1976). "Knickerbockers and Red Stockings, 1863–1884". Bounder from Wales — Lloyd George's Career before the First World War. Columbia & London: University of Missouri Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-8262-0203-9.

- ^ a b "James Callaghan". infobritain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Hazel Shearing; Kathryn Snowdon (30 May 2021). "Boris Johnson marries Carrie Symonds at Westminster Cathedral". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "When Rishi Sunak celebrated Diwali at 11 Downing Street, took oath on 'Bhagavad Gita'". Deccan Herald. 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Murphy, Neil (24 October 2022). "Rishi Sunak: young, wealthy and the UK's first Hindu prime minister". The National. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Non-religious Prime Ministers: a history". Humanists UK. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Clement Attlee". Humanist Heritage.

- ^ Hatton, Ben; Wheeler, Richard (2 August 2022). "Nicola Sturgeon is an 'attention seeker' best ignored, claims Liz Truss". PA Media. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022.

- ^ Hazell, Will (10 September 2022). "Atheist Keir Starmer avoids reference to God in pledge of loyalty to King Charles III". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Edwardes, Charlotte (22 June 2024). "'You asked me questions I've never asked myself': Keir Starmer's most personal interview yet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 July 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Englefield, Dermot; Seaton, Janet; White, Isobel (1995). Facts About the British Prime Ministers. Mansell. ISBN 9780720123067.

- ^ "James Callaghan". HMSO. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007.

- ^ "Prime Ministers in History: Spencer Perceval". Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 25 August 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Dasgupta, Reshmi (22 July 2022). "Can tall tales 'short' circuit Rishi Sunak's campaign?". Firstpost. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Prest, John (21 May 2009). "Russell, John, first Earl Russell (1792–1878)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24325. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Statesmen and stature: how tall are our world leaders?". The Guardian. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Attenborough, W. (2014). Churchill and the Black Dog of Depression. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 175–186. ISBN 9781137462299.

- ^ "Harold Macmillan". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022.

- ^ Hinsliff, Gaby (10 October 2009). "How Gordon Brown's loss of an eye informs his view of the world". The Observer. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ Clark, Ronald (2011). The Life of Bertrand Russell. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4482-0215-7.

- ^ Middlemass, Keith; Barnes, John (1969). Baldwin: A Biography. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 1070.

- ^ Morris, Nigel (11 November 2008). "Wilson 'may have had Alzheimer's when he resigned'". The Independent. Retrieved 20 November 2022.