Trespass (album)

| Trespass | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 23 October 1970 | |||

| Recorded | July 1970 | |||

| Studio | Trident (London) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:42 | |||

| Label | Charisma | |||

| Producer | John Anthony | |||

| Genesis chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Trespass | ||||

Trespass is the second studio album by the English rock band Genesis. It was released on 23 October 1970 by Charisma Records, and is their last album with original guitarist Anthony Phillips and their only album with drummer John Mayhew.

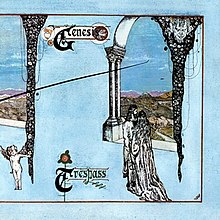

Genesis turned professional in autumn 1969, and began to rehearse intensely and play live shows. After several months of touring they secured a recording contract with Charisma Records, and entered Trident Studios in London in July 1970 to record Trespass. The music marked a departure from more pop-oriented songs, as displayed on their first album From Genesis to Revelation, towards folk-flavoured progressive rock. This ranged from light acoustic pieces with multiple twelve-string guitars such as "Dusk", to the heavier live favorite "The Knife". The sleeve, featuring a knife slash across the front, was designed by Paul Whitehead. It was the first of three covers designed by Whitehead for the band.

Shortly after recording, Phillips decided to leave the group, which almost caused Genesis to split. After discussing the situation, they agreed to continue, and replaced Mayhew with drummer and singer Phil Collins before they resumed touring. Trespass was not a major success upon release; it failed to chart in the UK and the US and it received some mixed reviews from critics, but it was commercially successful in Belgium, which helped sustain the band's career. A reissue briefly charted the UK top 100 in 1984.

Background and recording

[edit]In August 1969, Genesis decided to become a professional band. The founders – guitarist Anthony Phillips, bassist Mike Rutherford, vocalist and flautist Peter Gabriel, and keyboardist Tony Banks – had been joined by drummer John Silver.[4] They split from producer Jonathan King and decided to write more complex material than the straightforward pop on their first album From Genesis to Revelation. Gabriel recalled that the group wanted to explore and mix musical styles.[5] The group bought new equipment, including a bass guitar and a Hammond organ, and recorded songs at Regent Studios for a demo, including "White Mountain" and "Family" (which became "Dusk"). Silver then left to study in the US.[4]

In November, Genesis played their first live shows as a professional band, touring the local university circuit, with new drummer John Mayhew.[6] Mayhew, the oldest and most experienced musician, came from a different background to the rest of the band. Phillips recalled that, despite their efforts to make him feel comfortable, the drummer was unsure of his playing.[7] Also in November, Genesis friend and ex-schoolmate Richard MacPhail arranged for them to take up residence in his family's abandoned weekend retreat house in Wotton, Surrey, called Christmas Cottage. Genesis remained there for six months, a period of intense songwriting in between concerts which would produce the bulk of the material for Trespass.[8]

The group wanted to branch out from their earlier pop-oriented style, and write and perform songs that were unlike any other band at the time.[9] Banks was also transitioning his main instrument from piano to Hammond organ, which was a difficult process for him.[10] Rutherford later said that gigging was "tough, but a good way of getting the music into shape".[11] Two songs that made it to the next album, "Looking for Someone" and "Stagnation", were recorded for a BBC session in February 1970.[12] That same month, growing interest from audiences drew the attention of talent scouts and led to Threshold Records inviting Genesis to record "Looking For Someone" at De Lane Lea Studios. However, their chance for a recording contract with Threshold went up in smoke when Banks started arguing with producer Mike Pinder, saying they needed to do another take because he had played a wrong note on his organ.[13]

In March 1970, they secured a six-week residency at Ronnie Scott's jazz club in Soho, London, during which they were spotted by Charisma Records producer John Anthony. He persuaded label boss Tony Stratton Smith to sign them.[14] In July 1970, they retreated to Trident Studios in London to record a new album.[15] Anthony joined them as their producer and engineer, and the songs were recorded on 16-track tape.[9] Phillips remembered that recording was "slightly more sophisticated" than on From Genesis to Revelation, with the 16-track capability allowing them to multitrack solos, "which would have been unheard of on the previous album."[16] Rutherford and Phillips thought Anthony disliked having someone "drop in" individual parts, remembering by way of example that while recording "Stagnation", Rutherford had to listen to several minutes of the track before putting down a guitar part, by which time he had become too nervous and played it incorrectly.[16][17] The group had written an abundance of material, but with very little studio time in the budget there was no real opportunity to consider which songs should go on the album, and they had to simply record the songs which they had played the most in rehearsals and concerts.[18] They worked well with Anthony, and later recalled that his contributions were important and helped shape the album.[19]

Songs

[edit]Rutherford said that Trespass was the only Genesis album where each track was contributed to by each band member equally; every other album contained songs that were written by one or two individuals, with only minor contributions from the remaining members.[20] Phillips likewise remarked that during the months at Christmas Cottage, Genesis's habit of writing songs in their pre-Genesis writing partnerships (Phillips-Rutherford and Banks-Gabriel) was broken and they all began collaborating on writing each work.[21] Banks felt that the old songwriting process was still present to an extent, with most of the songs originating from one of the two pairs before being brought to the group for further development.[22] Banks later said that "we had played live quite a bit and every song on the album had been performed on stage. We had a selection of at least twice as many songs as appeared on the album, and the versions changed rapidly."[9] Rutherford recalled that since the songs had already been composed, arranged, and refined during live performances, there was no need to work out such things in the studio the way they did for later albums.[23]

The 1969 album In the Court of the Crimson King by King Crimson was a heavy influence on Genesis, with a copy being played endlessly during their extended stay at Christmas Cottage.[24] The band also drew from Gabriel's soul influences, along with classical, pop and folk music, and made regular use of Phillips and Rutherford's twelve-string guitar playing.[5] To break the twelve-string guitar out of its traditional role as a background instrument and allow the listener to hear its individual notes, the band ran the twelve-string guitars through an old tape recorder instead of the conventional method of putting the microphone on the sound hole, against engineer Robin Cable's objections.[10] Gabriel was particularly fond of the combined twelve-string guitars and thought they gave the group a more unique and innovative sound.[25]

The album opens with "Looking for Someone", beginning with Gabriel's vocal accompanied only by an organ, later described as being "idiosyncratic enough to set them apart from the herd within seconds".[26] Gabriel came up with the song as a soul piece, and it was then extended and developed by the group into a more folk direction.[27] The coda at the end of the song was written by the group as a whole.[28] Paul Stump wrote in 1997 that there is "the barefaced presence of a riff" from "I Am the Walrus" by the Beatles in the song.[29]

"White Mountain" originated with a twelve-string guitar theme composed by Rutherford and Phillips, for which Phillips has cited Mary Hopkin's rendition of "Those Were the Days" as a likely influence.[30] Banks wrote the lyrics.[31]

"Visions of Angels" was recorded for the previous album From Genesis to Revelation, but left off because the band did not think it was good enough in its present form.[31] It originated from a piano piece by Phillips at a time when his piano technique was limited, but could produce a "plodding" style similar to songs by the Beach Boys and the Beatles.[32] It has a more straightforward verse/chorus structure than some of the other songs.[33][34] Genesis subsequently reworked and expanded it with a new middle section which was written by the group as a whole.[31] Phillips commented that while he was "rather heartbroken" when the song was rejected for From Genesis to Revelation, in retrospect it was a blessing, since if they had included it on that album, it never would have been developed into its best possible form.[32] He also said that Gabriel realized sometime between the recording for From Genesis to Revelation and Genesis going on tour for the first time that Phillips had written the lyrics as a love song to Jill Moore, Gabriel's girlfriend (and later wife), and it is likely that Genesis changed the lyrics before recording Trespass.[35]

The whole group worked on the music for "Stagnation", and Gabriel added lyrics to it.[36] It was one of several Genesis songs to reuse sections of their never-recorded epic "The Movement".[37] "Stagnation" and "Dusk" showed Phillips and Rutherford's combined twelve-string sound, along with Banks taking leads on piano, organ and Mellotron.[38] The organ lead uses a surreal descending note which Banks produced by turning the organ off and then turning it back on.[37] Rutherford later recalled there were around ten acoustic guitars on part of "Stagnation", but they cancelled each other out in the final mix.[39] Gabriel described the track as a "journey song" with its lack of a more typical verse/chorus structure and the variety of mood changes it presents.[40] Sections were removed or altered, but the introduction remained unchanged.[41] The vocal effect on the section referencing "bitter minnows amongst the weeds and slimy water" was created by having Gabriel sing into a narrow tube with the intent of making it sound like he was underwater.[42] "Dusk" originated with a piece written by Phillips and Rutherford, with Phillips writing most of the lyrics.[42]

The music to the verse/chorus section of "The Knife" was written by Gabriel and Banks, the lyrics were written by Gabriel and Phillips, and the remaining sections were written by all four founding members of Genesis.[43] It was originally titled "The Nice" as a tribute to the Nice, and the organ part on the track was styled to resemble the playing of Nice keyboardist Keith Emerson.[28] As fans of that group, Genesis were inspired to put together a heavier rock song which Gabriel said was "something more dangerous" compared to their delicate acoustic numbers. He added: "It was the first peak of a darker energy that we discovered".[44] It lasted up to 19 minutes in concert, but was reduced to nine for the album.[45] Gabriel wrote the lyrics as a parody of a protest song.[38] The song's spoken word interlude, in which a group of soldiers fire on a crowd of protesters, was inspired by the Kent State shootings from the previous spring.[46]

Phillips later recalled that the songs "Everywhere is Here", "Grandma", "Little Leaf", "Going out to Get You", "Shepherd", "Moss", "Let Us Now Make Love" and "Pacidy" were not developed further in the studio.[47] Banks said that "Going out to Get You" was too long to fit on the album as well as "The Knife", and the latter song had to have a portion of it cut out to fit on the LP.[9]

Artwork

[edit]The album cover was painted by Paul Whitehead and features an engraving by Hungarian illustrator Willy Pogany. Whitehead also did the covers for the band's next two albums.[48] Wanting his work to represent the band's music, Whitehead sat in on several Genesis rehearsals to get inspiration.[49] The cover showed two people looking out of a window at mountains, which represented the pastoral themes of some of the songs.[50] Whitehead had finished the cover and then the band added "The Knife" to the running order. Feeling that the cover no longer fitted the mood of the album, they asked Whitehead to re-design it; when he was reluctant to do so, the band members inspired him to slash the canvas with an actual knife.[48]

Tony Banks has said Trespass is his favorite of the three covers Whitehead did for Genesis, feeling it eloquently captured the two different sides of Genesis.[49]

Whitehead's original illustrations for the three albums were stolen from the Charisma archives when it was sold to Virgin Records in 1983. Whitehead claimed that Charisma staff got wind of the imminent sale and proceeded to loot its office.[51]

Release

[edit]Trespass was first released in the UK on the Charisma label in October 1970.[52][53] In the US, it was first issued on ABC's jazz label, Impulse!.[54] "The Knife" was released as single (split into two parts) in June 1971, but did not chart.[55]

The album was reissued by the main ABC Records label in 1974;[56] then, after MCA Records bought out ABC, it was reissued on the MCA label.[57] It was issued on CD in 1994 as a definitive edition remaster. A SACD/DVD double disc set (including new 5.1 and Stereo mixes) was released in 2008.[58]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Rolling Stone | (unfavorable)[60] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Daily Vault | A−[62] |

Trespass sold 6,000 copies on its original release and helped the band build up a live following.[9] The album charted at No. 1 in Belgium, which led to the band's first overseas concerts there in January 1972.[63]

The album had a mixed reception by the music press at the time of its release. Jerry Gilbert, writing in Sounds, gave a positive review and singled out "Visions of Angels" and "White Mountain". A review in Melody Maker said the album was "tasteful, subtle and refined",[64] and named it "Album of the Month", despite it being the same month as prestigious albums such as Led Zeppelin III, Atom Heart Mother, and Tumbleweed Connection.[24] Rolling Stone printed an extremely brief but unambiguously negative review of the 1974 reissue, saying "It's spotty, poorly defined, at times innately boring, and should be avoided by all but the most rabid Genesis fans."[60] AllMusic's later retrospective review was only slightly more forgiving, summarising that the album "is more interesting for what it points toward than what it actually does". They also commented that the guitars are so low in the mix that they are almost inaudible, leaving Banks's keyboard instruments far more prominent. They considered this troublesome because Banks having a noticeable role "isn't the Genesis that everyone came to know".[59]

Following the band's growth in popularity in the 1980s, Trespass reached its peak of No. 98 in the UK for one week in 1984.[52]

Aftermath

[edit]

Shortly after recording Trespass, Phillips quit the group.[65] He had confided in Rutherford (his long-time friend) that he was thinking of leaving after a concert at Kingston Polytechnic on 9 July 1970, and announced to the whole band that he was leaving at the end of a show in Hayward's Heath on 18 July.[66] According to Genesis road manager and friend Richard Macphail, the reason for Phillips's departure was the onset of acute stage fright that became so severe that Phillips began to suffer an "out of body experience on stage."[67] Phillips confirmed, "My leaving was nothing to do with the music; it was just due to stage fright and my health, really."[68] He initially feared that Genesis would not be able to continue without him, but with Banks gaining confidence with the organ and Rutherford having grown into a major songwriter, he ultimately recognized that the band no longer needed him.[69] While Phillips later described the Trespass recording sessions as "pleasant" and not considerably difficult,[70] Rutherford recalled that Phillips looked unwell during the recording sessions, and he worried that Phillips's departure might mean the end of Genesis. After the group drove back from the last gig in Hayward's Heath to Gabriel's house in Chobham, they decided they would carry on.[71]

In the liner notes to the Genesis box set Genesis Archive 1967–75, Banks claims "Let Us Now Make Love", one of Phillips's songs, was not recorded for the album because the group thought it had the potential of a single, but following the guitarist's sudden departure following the album's completion, it was never recorded in the studio. A live version was released on the box set, performed in February 1970.[72]

At the same time, the group decided to replace Mayhew with a more suitable drummer. He was older than the rest of the band and considered an outsider, and lacked confidence.[73] Though Mayhew often wrote poetry and even had some published in a literary magazine when he was 12, he never participated in Genesis's songwriting.[74] An urgent replacement was required to fulfil live dates to promote Trespass. Phil Collins auditioned and joined in August, and the album was released in October.[75][76] The group could not find a suitable replacement for Phillips, so they resumed gigging as a four-piece.[64] In late 1970, they appeared on the television show Disco 2 to promote the album with Phillips' replacement, Mick Barnard. The group mimed with Gabriel singing live, who recalled the performance was "disastrous". The group auditioned Steve Hackett as a replacement in December and he officially joined the band the following month.[19]

Track listing

[edit]All songs written by Anthony Phillips, Mike Rutherford, Peter Gabriel, and Tony Banks.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Looking for Someone" | 7:06 |

| 2. | "White Mountain" | 6:44 |

| 3. | "Visions of Angels" | 6:52 |

| Total length: | 20:42 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Stagnation" | 8:51 |

| 2. | "Dusk" | 4:13 |

| 3. | "The Knife" | 8:56 |

| Total length: | 22:00 | |

Personnel

[edit]Genesis

- Peter Gabriel – lead vocals, flute, accordion, tambourine, bass drum

- Anthony Phillips – acoustic 12-string guitar, lead electric guitar, dulcimer, vocals

- Tony Banks – Hammond organ, grand piano, Mellotron, acoustic 12-string guitar, vocals

- Mike Rutherford – acoustic 12-string guitar, electric bass guitar, classical guitar, cello, vocals

- John Mayhew – drums, percussion, vocals

Production

- John Anthony – producer

- Robin Geoffrey Cable – engineer

- Paul Whitehead – layout

- Nick Davis – mixing (2008 release)

- Tony Cousins – mastering (2008 release)

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1984) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Albums (OCC)[77] | 98 |

| Chart (2024) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Hungarian Physical Albums (MAHASZ)[78] | 25 |

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Molanphy, Chris (31 May 2019). "The Invisible Miracle Sledgehammer Edition". Hit Parade | Music History and Music Trivia (Podcast). Slate. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel — Polar Music Prize". www.polarmusicprize.org. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Get 'Em Out By Friday Genesis: The Official Release Dates 1968-78" (PDF).

- ^ a b Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 24.

- ^ a b "How Genesis Found Their Prog-Folk Focus With "Trespass"". Ultimate Classic Rock. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 37.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 26:03–27:16.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 46-48.

- ^ a b c d e Welch 2011, p. 26.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 54.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 29.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Rutherford 2014, p. 84.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 51-52.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 11:42–12:10.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 50-51.

- ^ a b Watts, Michael (23 January 1971). "Reading from the Book of Genesis". Melody Maker. p. 15.

- ^ Neer, Dan (1985). Mike on Mike [interview LP], Atlantic Recording Corporation.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 53.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 10:06–10:46.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 11:15–11:41.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 60.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 8:11–9:14.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 32.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 24:15–24:38.

- ^ a b Genesis 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Stump, Paul (1997). The Music's All that Matters. Quartet Books. p. 175. ISBN 0-7043-8036-6.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 62-63.

- ^ a b c Giammetti 2020, p. 63.

- ^ a b Trespass 2007, 22:12–24:03.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Hegarty & Halliwell 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 64.

- ^ Genesis 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 65.

- ^ a b Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 33.

- ^ Rutherford 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 14:41–15:42.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 15:42–16:02.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 66.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 67.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 20:10–22:03.

- ^ Welch 2011, p. 30.

- ^ "Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming": Musical Framing and Kent State Archived December 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Chapman University Historical Review. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ Negrin, David. "An Interview with Anthony Phillips". Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b Romano 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 68.

- ^ Hegarty & Halliwell 2011, p. 58.

- ^ "Interview with Paul Whitehead". 25 July 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 245.

- ^ Trespass (Media notes). Charisma Records. 1970. CAS 1020.

- ^ Trespass (Media notes). Impulse!. 1970. AS-9205.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 249.

- ^ Trespass (Media notes). ABC Records. 1974. ABCX-816.

- ^ Trespass (Media notes). MCA Records. 1977. ABCX-816.

- ^ Trespass (Media notes). Virgin / MCA. CASCDX 1020.

- ^ a b Eder, Bruce. "Trespass – Genesis | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Gordon (1 August 1974). "Genesis: Trespass : Music Reviews". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008.

- ^ Nathan Brackett; Christian David Hoard (2004). The new Rolling Stone album guide. Simon & Schuster. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

rolling stone genesis album guide.

- ^ Feldman, Mark (2019). "The Daily Vault Music Reviews : Trespass". dailyvault.com. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 58.

- ^ a b Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 41.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 34.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 43.

- ^ Richard Macphail, My Book of Genesis, 2017 p. 81

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Trespass 2007, 13:18–13:55.

- ^ Rutherford 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Genesis – Archive 1967 – 75 (Media notes). Virgin / EMI. 1998. p. 3. CD BOX 6.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 35.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 62.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 37.

- ^ Welch 2011, p. 25.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista (fizikai hanghordozók) – 2024. 40. hét". MAHASZ. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

Sources

- Banks, Tony; Collins, Phil; Gabriel, Peter; Hackett, Steve; Rutherford, Mike (2007). Dodd, Philipp (ed.). Genesis. Chapter and Verse. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84434-1.

- Banks, Tony; Collins, Phil; Gabriel, Peter; Phillips, Anthony; Rutherford, Mike (10 November 2008). Genesis 1970–1975 [Trespass] (DVD). Virgin Records. UPC 5099951968328.

- Bowler, Dave; Dray, Bryan (1992). Genesis: A Biography. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-06132-5.

- Giammetti, Mario (2020). Genesis 1967 to 1975 - The Peter Gabriel Years. Kingmaker. ISBN 978-1-913218-62-1.

- Hegarty, Paul; Halliwell, Martin (2011). Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock since the 1960s. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-441-11480-8.

- Romano, Will (2010). Mountains Come Out of the Sky: The Complete Illustrated History of Prog Rock. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-8793-0991-6.

- Rutherford, Mike (2014). The Living Years. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-472-11035-0.

- Welch, Chris (2011). Genesis: The Complete Guide to their Music. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-857-12739-6.